Walt Whitman

Walt Whitman had a connection to Lincoln. They passed each other often on their walks around Washington, when they would famously tip hats in acknowledgement. Whitman was greatly moved by Lincoln's assassination, and wrote his perhaps best and most renowned poem, "My Captain?, in his honor. "My Captain" was first published on November 4, 1865, and Whitman later included it in the collection ?Leaves of Grass? and recited the poem at several lectures on Lincoln?s death.This is a portion of Whitman?s poem showing his reverence for Lincoln:?Oh Captain. ?O Captain! My Captain! our fearful trip is done;The ship has weather'd every rack, the prize we sought is won;The port is near, the bells I hear, the people all exulting,While follow eyes the steady keel, the vessel grim and daring:But O heart! heart! heart!O the bleeding drops of red,Where on the deck my Captain lies,Fallen cold and dead.Whitman had recently published "Slang in America" in the North American Review, which was edited and published by C. Allen Thorndike Rice. In 1885, Rice set about to compile memories of people who knew Lincoln and he went to Whitman for a piece, for which he would pay $33. The title was "Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln by Distinguished Men of His Time," compiled by Rice and published 1886 by the North American Publishing Co. There would be contributions by Ulysses S. Grant, Frederick Douglass, Henry Ward Beecher, Walt Whitman, Cassius Clay and many others.Excerpt from Whitman's:"Abraham Lincoln's was really one of those characters, the best of which is the result of long trains of cause and effect?needing a certain spaciousness of time, and perhaps even remoteness, to properly enclose them?having unequaled influence on the shaping of this Republic (and therefore the world) as to-day, and then far more important in the future."Autograph Letter Signed, Camden, New Jersey; October 21, 1885, to James Redpath, an editor at the North American Review, about this Lincoln article and getting paid for his other work: "Yours rec'd with the 50 for 'Slang in America' which sum I heartily thank Mr Rice & you for, as it is ample - I am in miserable brain condition & half blind - waiting to feel better. Will set to work forthwith however on finishing the Lincoln article & something else for you." Signed, "Walt Whitman." Stamped "Answered" at top right and annotated, "file" at top left.Whitman had recently moved into his own house at 328 Mickle Street in Camden after living with his brother since 1873 to recover from a stroke. Although he had been very productive and physically active during the years he lived with his brother, by the time he moved to Mickle Street he was bedridden and frail; he remained so for the rest of his life. A great association letter mentioning Lincoln, for whom Whitman had tremendous respect and admiration. Lincoln's leadership and assassination had a profound impact on Whitman's life and work.

Winston Churchill

The Blitz, from September 7, 1940?May 11, 1941, was an intense bombing campaign undertaken by Nazi Germany against Great Britain during World War I. For eight months the Luftwaffe dropped bombs on London and other strategic cities. The attacks were authorized after the British carried out a nighttime air raid on Berlin. The offensive came to be called the Blitz after the German word blitzkrieg (?lightning war?).When photographer Walter Stoneman arrived at 10 Downing Street on April 1, 1941, with the Blitz ongoing, he realized this was a historic occasion. He recorded the exact time he took the Prime Minister's picture as 3pm. At this moment, Churchill was waiting for word on Germany's fateful invasion of Yugoslavia, information made possible in part by the English decryption of German Enigma messages. The photograph Stoneman took that day captures Churchill's resolve and the gravity of the moment. It remains, along with Karsh's portrait (done a full 9 months later), an enduring symbol of Churchill at war. Churchill liked the Stoneman image and gave out copies signed on the mount to notables and others; one copy sat on Stalin's desk.A black and white Stoneman photograph of Churchill, 6 _ x 7 _ inches, mounted to an overall size of 7 _ x 10 inches, showing Churchill wearing a dark suit and bowtie, sitting with his right arm propped on the Cabinet Office table. It is signed and dated on the mount, "Winston S. Churchill / 1946." With the photographer's imprint on verso.

Grover Cleveland

A very rare document relating to U.S./Chinese relations and the exclusions of Chinese immigrantsIn the 1850s, Chinese workers migrated to the United States, first to work in the gold mines, but also to take agricultural jobs, and factory work, especially in the garment industry. Chinese immigrants were particularly instrumental in building railroads in the American west, and as Chinese laborers grew successful in the United States, a number of them became entrepreneurs in their own right. As the numbers of Chinese laborers increased, so did the strength of anti-Chinese sentiment among other workers in the American economy. This finally resulted in legislation that aimed to severely limit future immigration of Chinese workers to the United States,.American objections to Chinese immigration took many forms, and generally stemmed from economic and cultural tensions, as well as ethnic discrimination. Most Chinese laborers who came to the United States did so in order to send money back to China to support their families there. At the same time, they also had to repay loans to the Chinese merchants who paid their passage to America. These financial pressures left them little choice but to work for whatever wages they could. Non-Chinese laborers often required much higher wages to support their wives and children in the United States, and also generally had a stronger political standing to bargain for higher wages. Therefore many of the non-Chinese workers in the United States came to resent the Chinese laborers, who might squeeze them out of their jobs. Furthermore, as with most immigrant communities, many Chinese settled in their own neighborhoods, and tales spread of Chinatowns as places where large numbers of Chinese men congregated to smoke opium or gamble. Some advocates of anti-Chinese legislation therefore argued that admitting Chinese into the United States lowered the cultural and moral standards of American society. Others used a more overtly racist argument for limiting immigration from East Asia, and expressed concern about the integrity of American racial composition.To address these rising social tensions, from the 1850s through the 1870s the California state government passed a series of measures aimed at Chinese residents, ranging from requiring special licenses for Chinese businesses or workers to preventing naturalization. Because anti-Chinese discrimination and efforts to stop Chinese immigration violated the 1868 Burlingame-Seward Treaty with China, the federal government was able to negate much of this legislation. In 1880, the Hayes Administration appointed U.S. diplomat James Angell to negotiate a new treaty with China. The resulting Angell Treaty permitted the United States to restrict, but not completely prohibit, Chinese immigration. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which suspended the immigration of Chinese laborers (skilled or unskilled) for a period of 10 years. The Act also required every Chinese person traveling in or out of the country to carry a certificate identifying his or her status as a laborer, scholar, diplomat, or merchant. The 1882 Act was the first in American history to place broad restrictions on immigration.In 1888, Congress took exclusion even further and passed the Scott Act, which made reentry to the United States after a visit to China impossible, even for long-term legal residents. The Chinese Government considered this act a direct insult, but was unable to prevent its passage. In 1892, Congress voted to renew exclusion for ten years in the new Geary Act, that extended the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 by adding onerous new requirements.But the United States wanted even more, and in 1894 President Cleveland authorized the Secretary of State to negotiate another treaty - to be known as the Gresham-Yang Treaty. This treaty was successfully negotiated, and later that year the Gresham-Yang Treaty was signed between the United States and China, in which the Chinese Qing dynasty consented to measures put in place by the United States prohibiting Chinese immigration in exchange for the readmission of previous Chinese residents, thus in effect agreeing to the enforcement of the Geary Act. This was the first time the United States government barred an entire ethnic group from entering the mainland United States. However, despite signing the Gresham-Yang Treaty, the Chinese government held many grievances against the United States related to the various "exclusion laws" passed, and the manner under which they were being enforced.Document signed as president, Washington, March 1, 1894, being Cleveland?s original authorization to seek what became the Gresham-Yang Treaty. In it, President Cleveland directs the Secretary of State to ?cause the Seal of the United States to be affixed to my Full Power authorizing him to negotiate, conclude and sign a Treaty in regard to the subject of emigration between the United States of America and the Emperor of China.?

Napoleon Bonaparte

"You will allocate 1,500,000 francs to send to the army of Portugal, which, with the 3,500,000 francs that I gave you to this army, will make a total of 5,000,000. You will send 1,000,000 to the Central army. These funds will be taken from the funds of the armies of Spain and Portugal of 1810."The Peninsular War was a key focal point of the Napoleonic Wars, one that drained French forces and energies and led to a rise to leadership of the Duke of Wellington, who would be Napoleon?s nemesis. It pitted the French and its allied armies against the Anglo-Portuguese armies under Wellington and Spanish insurgents. The war began when France, with the consent of Spain, crossed the Iberian Peninsula and invaded Portugal in 1807. In May 1808, France turned on its ally when Napoleon handed the throne of Spain to his brother Joseph and forced the abdication of King Carlos IV. A puppet Spanish government was formed, but an insurrection broke out against it that required France to expend significant resources to counter. Where once Napoleon had bragged that 12,000 men could conquer Spain, now he required 80,000 to keep peace in just a portion. That number grew exponentially over time.British military intervention became a reality for Napoleon in August 1808, when the Duke of Wellington landed in Portugal and successfully threw the French out of that country. The next few years saw competing incursions, with the troops led by Wellington attempting to push the French eastward and the French attempting renewed and unsuccessful invasions of Portugal.1811 saw a series of major and minor confrontations between French General Massena and General Wellington along the Portuguese frontier. Wellington would come out the main victor but Napoleon was pouring resources into the Peninsula to stem the bleeding.This important letter shows him funding the coming conflicts with the English and Portuguese.Letter signed, Paris, March 8, 1811 to Marshall Berthier, Minister of War. "My cousin, Give the order for 3 million to go from Bayonne to Burgos. You will distribute 500,000 francs between the corps of the province of Santander and the other districts of the Northern army which need it the most. You will allocate 1,500,000 francs to send to the army of Portugal, which, with the 3,500,000 francs that I gave you to this army, will make a total of 5,000,000. You will send 1,000,000 to the Central army. These funds will be taken from the funds of the armies of Spain and Portugal of 1810. Let me know what is returned by the Treasury for 1810 and for this year."

Thomas Jefferson

Among the recipients were his servants, chef, coachman, and others, during a time when Meriwether Lewis was living with him?A remarkable letter showing the fragile nature of the former President's and founding father's personal financial state and how he juggled funds?This letter, unpublished and whose content was not known till now, was last sold in 1929 through the firm of Thomas Madigan in New York City. It was acquired by us from the heirs of that buyer.https://vimeo.com/973483379?share=copy?Thomas Jefferson lived with his debt throughout much of his life, inheriting debt from his father and living beyond his means with large projects and lavish lifestyle. Eventually this would lead to the sale of his property and land. And his Presidential salary did little to alleviate this. His personal household expenses were such that he was essentially paying bills paycheck to paycheck, a sharp contrast to how we imagine the personal finances of an American president today.John Barnes emigrated from England to America about 1760. He was a tea merchant and grocer in New York and Philadelphia, relocating to the latter city when the federal government moved there in 1791. Barnes remained in Philadelphia until 1800, when he moved to Washington to serve as a contractor with the Treasury Department. Jefferson had known him for many years and appointed him customs collector at Georgetown in 1806, a position Barnes held until his death. He was during much of this time also Jefferson's banker and commission agent, helped him manage the investments of Tadeusz Kosciuszko and William Short, and supplied him with groceries from 1795 until Jefferson's retirement. Barnes kept his personal house running during his time in Washington at the Presidential Mansion.In May 1802, Jefferson wrote a letter with dire news of his finances. "I received yesterday your favor of the 10th. and am sincerely concerned at the disappointment at the bank of Columbia [which evidently would not supply him with needed funds]. This proves farther the propriety of my curtailing expenses till I am within the rigorous limits of my own funds, which I will do. in the mean time I must leave to your judgment to marshall our funds for the most pressing demands, till I can be with you."In June, Jefferson wrote to Barnes explaining what the main outstanding bills would be that they might trim. These were the prime recurring bills of his household presidency during this time. "Th: Jefferson has been taking a view of his affairs, and sends mr Barnes a statement of them. if it should be possible to get through the month of July without the aid of the bank, by my giving a new note there on the 4th of August for 2000. Doll. we should on that day be almost completely relieved, and the receipt of the 4th. of October will take up the note, and leave me entirely out of debt. Perhaps we may not be able to squeeze down the houshold expenses to 600."LeMaire?s bills @ 75. D a week would be 337.Dougherty?s are per month about 70.groceries about 120.servant?s wages 152"Lemaire was his steward and helped with meal preparation. Doughtery was his coachman and servant. Among the other servants were former slaves, including James Hemings. There were white and free black servants, some remaining for long periods of time and living there or close; others would come and go and performed specific tasks.Money was also paid for ad hoc expenses and money sent home to Monticello and to his daughter. Jefferson evidently felt that the largest chunk and perhaps where he could trim expenses was his domestic situation.Interestingly during this time Meriwether Lewis was serving as Jefferson's secretary and living in the presidential mansion.He evidently provided that note in late Summer to the bank and hoped that it would last a while, a point on which Barnes evidently had some concern. Jefferson did his own tally and explained the situation to Barnes in this letter, explaining that he calculated it would last him through the winter.Autograph letter signed, Washington October 15, 1802, to John Barnes. ?In answer to my letter which had mentioned that I should be obliged to go again into the bank, you were so kind as to say, the balance then being between $1700 and $1800, that from this balance you could accommodate yourself for 2 or even 4 months rather than take it from the bank. I have taken an exact view of all the calls which will come to me through the winter and send you a statement of them and of the times they must be answered with the immediate sums of compensation to be received and applied to meet them. By this it appears that the balance due from me will always be under $1700 and will be completely surmounted March 4. This is longer than you had contemplated, and I therefore propose that the moment you find any inconvenience from it, now or any time hence, you accept my note to be discounted at the bank, which I shall always be ready to give you. Accept assurance of my affectionate esteem??The Papers of Thomas Jefferson notes that "A letter from TJ to Barnes dated 15 Oct. is recorded in SJL but has not been found."This letter, unpublished and whose content was not known till now, was last sold in 1929 through the firm of Thomas Madigan in New York City. It was acquired by us from the heirs of that buyer.

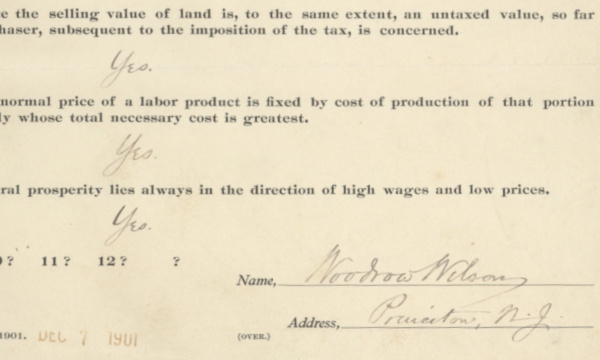

Woodrow Wilson

Likely a unique document, as we?ve never seen another anything like thisThe turn of the 20th century was a time in which there was much interest in political economy, and those working in that field were often polled to determine whether a consensus on questions of interest could be had. For example, in 1908 the American Economic Association Quarterly, based in Princeton, N.J., polled political economists, trying to elicit from them a consensus upon certain definitions and statements of principle, touching land, value, and land taxation. The result was published in an article entitled ?Agreements in Political Economy? A similar poll, likely from the same source in Princeton, was taken in 1901, with the political economists receiving a set of questions on which they might agree on a form headed ?Possible Agreements? One of the political economists included in the survey was Woodrow Wilson.In 1901 Woodrow Wilson was a professor at Princeton, holding that position from 1890-1902, after which he became President of Princeton University. He had written a number of books on politics and government, so was an obvious choice for inclusion in the poll. Among the positions taken by Wilson were that wages are primarily the product of labor; labor produces its own wages; the normal price of a labor product is fixed by cost of production of that portion of the supply whose total necessary cost is greatest; and general prosperity lies always in the direction of high wages and low prices.Document signed, headed ?Possible Agreements?, the questions relating to political economy drafted by the publisher, the responses written out by Wilson, Princeton, December 1901.1. ?Wages," while apparently drawn from capital and dependent upon capital, are primarily the product of labor; hence it is practically true that labor produces its own wages. Wilson says ?Yes.?2. ?Ground rent" is what land is worth for use. Wilson writes, ?Yes, though generally in practice less than the use is worth.?3. Public franchises" are exclusive free privileges granted to one or several persons incorporated, and from which the mass of citizens are excluded. These franchises usually pertain to land, including, as they do, (to use the language of the New York Legislative Ford Bill,) all & rights, authority or permission to construct, maintain or operate, in, under, above, upon or through, any streets, highways, or public places, any mains, pipes, tanks, conduits, or wires, with their appurtenances, Wilson responds, ?Yes, though I do not understand the use of the word ?free? by way of depiction in the first line.?4. A tax upon ground rent is a direct tax and cannot be shifted. Wilson says, ?Yes.?5. The selling value of land is, under present conditions in most of the American States, reduced by the capitalized tax that is laid upon it. Willson replies, ?Yes, so far as I understand the statement.?6. Hence the selling value of land is, to the same extent, an untaxed value, so far as any purchaser, subsequent to the imposition of the tax, is concerned. Wilson says, ?Yes.?7. The normal price of a labor product is fixed by cost of production of that portion of the supply whose total necessary cost is greatest. Wilson writes, ?Yes.?8. General prosperity lies always in the direction of high wages and low prices. Wilson answers with a strong ?Yes.?The document is signed ?Woodrow Wilson, Princeton, N.J.?A fascinating insight into Wilson?s opinions on matters of political economy, especially his belief that general prosperity lies in the direction of high wages and low prices. It is also likely unique, as we?ve never seen another document anything like this.

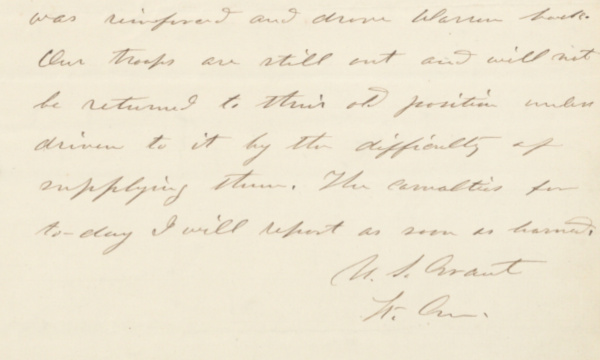

Ulysses S. Grant

The Confederates, Grant updates Stanton, ?were leaving a part of their dead for us to bury, our losses were three officers & eighteen men killed, eleven Officers & ninety-two men wounded and twenty-two men missing.?Grant writes: ?In front of one Brigade of Mott?s Div. he buried thirty-one of the enemy and counted twenty two graves besides some of which were large enough for five or six bodies each. Gen. Smythe estimates the loss of the enemy in his front at two hundred. Our captures for the day were about one hundred men, half of them taken by the Cavalry and the rest by the 5th & 2d Corps. This afternoon the 5th Corps advanced and drove the enemy back on to this Artillery, probably into his entrenchments, beyond Dabney?s Mill. The casualties for to-day I will report as soon as learned.?Unique in our experience, this being the only battle and casualty report from Grant we have ever seen.By February 1865, the stalemate around Petersburg had entered its eighth month. Lieut. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant planned a Union offensive to deprive the Confederates of supplies, and also hasten the fall of Petersburg. The Union objective was to send Brig. Gen. David McM. Gregg's cavalry out to the Boydton Plank Road to destroy all the Confederate supply wagons they could find, while the V Corps and II Corps provided support and kept the Confederates occupied to the north and east. Pursuant to plan, Union forces began to stretch their battle lines to the west in an attempt to get Gen. Robert E. Lee's under-strength army to do the same.On February 5th, Union Brig. Gen. David Gregg?s cavalry division rode out to the Boydton Plank Road via Reams Station and Dinwiddie Court House in an attempt to intercept Confederate supply trains. Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren with the Fifth Corps crossed Hatcher?s Run and took up a blocking position on the Vaughan Road to prevent interference with Gregg?s operations. Two divisions of the Second Corps under Maj. Gen. Andrew A. Humphreys shifted west to near Armstrong?s Mill to cover Warren?s right flank. Late in the day, Confederate Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon attempted to turn Humphreys' right flank near the mill but was repulsed. During the night, the Federals were reinforced by two divisions.On February 6th, Gregg returned to Gravelly Run on the Vaughan Road from his unsuccessful raid and was attacked by elements of Brig. Gen. John Pegram?s Confederate division. Warren pushed forward a reconnaissance in the vicinity of Dabney?s Mill and was attacked by Pegram?s and Maj. Gen. William Mahone?s divisions. Pegram was killed in the action. Although the Union advance was stopped, the Federals extended their siege works to the Vaughan Road crossing of Hatcher?s Run. On February 7, Warren launched an offensive and drove back the Confederates, recapturing most of the Union lines around Dabney's Mill that had been lost the day before. Thus, the Confederates kept the Boydton Plank Road open, but suffered attrition and were forced to further extend their thinning lines.Autograph letter signed ?U. S. Grant, Lt. Gen.,? two pages, Head Quarters Armies of the United States letterhead, City Point, Virginia, February 6, 1865, amidst the battle, to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, about the first day?s fighting and plans of the next day: ?In the affair of yesterday when the enemy attacked a port of the 2d Corps and were handsomely repulsed, leaving a part of their dead for us to bury, our losses were three officers & eighteen men killed, eleven Officers & ninety-two men wounded and twenty-two men missing. In front of one Brigade of Mott?s Div. he buried thirty-one of the enemy and counted twenty two graves besides some of which were large enough for five or six bodies each. Gen. Smythe estimates the loss of the enemy in his front at two hundred. Our captures for the day were about one hundred men, half of them taken by the Cavalry and the rest by the 5th & 2d Corps. This afternoon the 5th Corps advanced and drove the enemy [Grant strikes through ?inside this intrenchment?] back on to this Artillery, probably into this entrenchments, beyond Dabney?s Mill. Here the enemy was reinforced and drove Warren back. Our troops are still out and will not be returned to their old position unless driven to it by the difficulty of supplying them. The casualties for to-day I will report as soon as learned.?This is a true piece of history - the original report on the Battle of Hatcher?s Run, completely in the hand of Grant, as sent to Stanton. And considering the amount of time Lincoln spent at Stanton?s office, quite likely he would have seen or learned details of the report. It?s the only the battle and casualty report from Grant we have ever seen on the market.

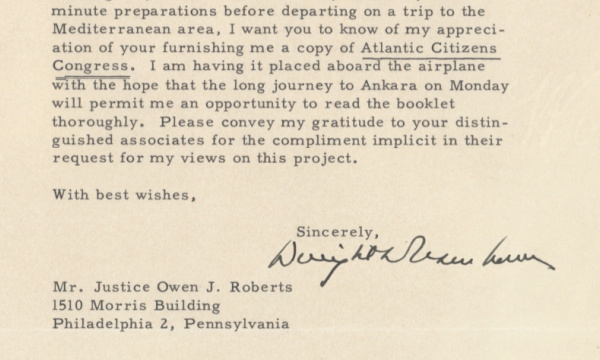

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Justice Owen J. Roberts resigned from the Supreme Court to advocate for a Federal Union of democracies, and to unite one group favoring world government and the other favoring Union of the DemocraciesFrom 1951-52, Eisenhower was the Allied Supreme Commander in Europe, which title included the post of head of NATO. In 1952, Turkey joined NATO, and Ike traveled to Ankara, Turkey, to seal with his presence the membership of Turkey in Europe.Justice Owen J. Roberts resigned from the Supreme Court in 1945, and was afterwards instrumental in forming the Atlantic Union, which would advocate for a Federal Union of Democracies, but with a gradual approach to final world union by way of regional unions. Two million people signed a petition that the U.S. and Great Britain unify, others wanted to start with the U.S. and Canada. Roberts said that although he approved of NATO, he thought it was a fine tradition but could not prevent war, and that permanent peace required a federation of likeminded peoples. Nor could the UN be relied upon, with the power the Soviets had in that body. In 1952, a new group was formed whose members agreed with Roberts? views, the Atlantic Citizens Congress, whose members were drawn partly from the Atlantic Union Committee, and partly from outside.Typed letter signed, on his letterhead, Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe, 1 March 1952, to Justice Owen J. Roberts, saying he is departing for Turkey and that he is grateful for receiving information on the new Atlantic Citizens organization. ?Dear Mr. Justice: Although my schedule is extremely rushed by last minute preparations before departing on a trip to the Mediterranean area, I want you to know of my appreciation of your furnishing me a copy of Atlantic Citizens Congress. I am having it placed aboard the airplane with the hope that the long journey to Ankara on Monday will permit me an opportunity to read the booklet thoroughly. Please convey my gratitude to your distinguished associates for the compliment implicit in their request for my views on this project.?Eight months later, Eisenhower is elected President of the United States.

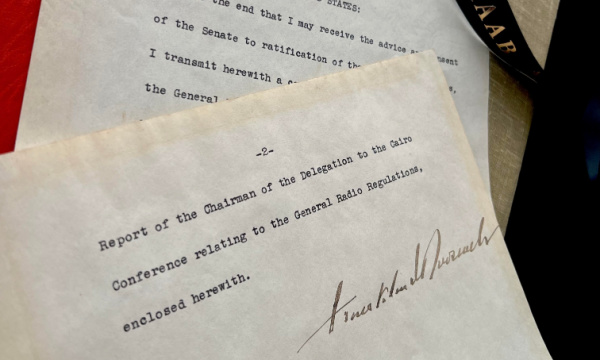

Franklin D. Roosevelt

?To the end that I may receive the advice and consent of the Senate to ratification of the revised regulations, I transmit herewith a certified copy of the revision of the General Radio Regulations annexed to the International Telecommunications Convention???A rare letter of any president to the U.S. Senate, and the first seeking the Constitutionally required ?Advice and Consent? that we have ever seenThe International Radiocommunication Conference was the first of the administrative radiocommunications conferences. It dealt with telegraph as well as telephone issues and was held simultaneously with the Administrative Telegraph and Telephone Conference in Cairo in 1938, under the banner of the International Telecommunication Conferences. The Telegraph Consultative Committee (CCIT) was reorganized and would function similarly to the Telephone Consultative Committee (CCIF). The CCIT would, from now on, be charged with the study of rate questions submitted to it by a plenipotentiary or administrative conference.The unification of code and plain language rates for telegrams within the European regime was adopted. The new fixed rate for coded telegrams was changed to 92% of the existing rate of plain language telegrams. The Telephone Regulations were modified to include the establishment of ?reversed-call charges? and ?urgent aircraft calls.? Urgent aircraft calls would be given priority over all other types of calls except urgent government calls.Participants agreed to use English as a supplementary language in conferences and meetings. The United States offered translating services for both of the conferences and compiled unofficial English translations. A vote determined that the Bureau would be responsible for future translations. A committee was created to resolve issues related to voting and to establish a recommendation for the next conference. A report was compiled and was approved for future voting at conferences.The increased demand and need for frequencies on intercontinental air routes was recognized. It was also decided that higher technical standards for transmitters through improved tolerance and band tables would be established. Limits were placed on the use of spark sets and maritime use was restricted to three frequencies. In addition, modifications were made to the regulations of the Maritime Mobile Service.The Radio Consultative Committee (CCIR) was reorganized. It would now be charged with the study of both technical and operations questions. Interval meetings would be held every three years.Changes were made to the Additional Radio Regulations with the establishment of a maximum charge of 20 centimes for radiotelegrams in the aeronautical service and the adoption of detailed regulations for new radio maritime letters.The Final Protocol to the General Radio Regulations was adopted and the agreement was ready to be ratified by the nations involved.A treaty is a binding agreement between nation-states that forms the basis for international law. Thus the agreement that resulted from this Conference was a form of treaty, and treaties signed by the United States must be ratified by the U.S. Senate to become law. Article II of the United States Constitution provides that the president "shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two-thirds of the Senators present concur.? President Roosevelt formally sought the Advice and Consent of the Senate to the Conference agreement.Typed letter signed, The White House, Washington, January 27, 1939, ?TO THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES? ?To the end that I may receive the advice and consent of the Senate to ratification of the revised regulations, I transmit herewith a certified copy of the revision of the General Radio Regulations annexed to the International Telecommunications Convention, signed at Madrid on December 9, 1932, adopted on April 8, 1938 by the International Telecommunication Conferences which convened at Cairo, Egypt, on February 1, 1938 to revise these regulations as well as the Additional Radio Regulations and the telephone and telegraph regulations also annexed to the Madrid Convention but which were not signed for the United States.Accompanying these revised general radio regulations is a certified copy of the Final Protocol to the General Radio Regulations, in which reservations thereto made by certain governments are recorded. The attention of the Senate is invited to the accompanying Report by the Secretary of State and to the Report of the Chairman of the Delegation to the Cairo Conference relating to the General Radio Regulations.?Letters of presidents to Congress are rarities.

In late 1881, the United States and the Kingdom of Choson (Korea) determined to establish diplomatic relations. They appointed negotiators, and on May 22, 1882, representatives of the two nations signed a treaty of amity and commerce at Chemulpo, Korea. Commodore R. W. Shufeldt was the negotiator for the United States. The treaty had been negotiated with the assistance of Chinese officials, since China had for many years had influence in Korea?s foreign affairs due to a historical tributary relationship between the two countries. In fact, however, Korea was an independent state and this key fact was acknowledged in the treaty.This was the first treaty Korea signed with a Western nation. The treaty - called the Shufeldt Treaty, or the Joseon?United States Treaty of 1882 - was a broad one, being a 14 article Treaty of Peace, Amity, Commerce and Navigation. The treaty established mutual friendship and mutual assistance in case of attack; and it also addressed such specific matters as extraterritorial rights for U.S. citizens in Korea, most favored nation trade status, protection for shipwrecked sailors, and institution of commerce regulations. The first U.S. diplomatic envoy arrived in Korea in 1883. U.S.-Korea relations continued until 1905, when Japan assumed direction over Korean foreign affairs.Document signed, as president, Washington, November 15, 1881, with President Arthur appointing the American negotiator for this historic U.S./Korea treaty ?I authorize and direct the Secretary of State to cause the Seal of the United States to be affixed to my letter to His Majesty the Emperor or King of Chosan (Corea) accrediting Commodore R. W. Shufeldt as Plenipotentiary of the United States to conclude a treaty of friendship and commerce, said letter being dated this day and signed by me, and for so doing this shall be his warrant.? Signed boldly at the conclusion by Arthur. The treaty Shufeldt negotiated was ratified and became effective in 1884, and being its first treaty with a western nation, was a landmark for Korea.

The only document signed by a president ordering the end of hostilities in a war waged by the United States that we have ever seen on the market?It is extremely rare that one comes across an original document signed by a president ordering the end of hostilities in a war waged by the United States subject to a declaration of war by Congress. We have, in our 35 years, seen just one, and it is this document.The United States had a long-term negative view of Spain and wanted it out of the Western Hemisphere. This was in part because of anti-Spanish feeling in the U.S. going back to colonial days. Then, in the War of 1812, the Spanish were allies of Britain, angering many Americans. Moreover, the Spanish policy of supplying Creek Indians with arms and ammunition through their territories in Florida further strained relations with the Americans on the frontier, and made Spain a threat to American expansion. The prospect of taking or acquiring East and West Florida from Spain became for many Americans a priority. The U.S. obtained West Florida in 1819, and purchased East Florida from Spain in 1821. In the years before the Civil War, anti-Spanish feelings remained, and Americans in the South wanted to obtain Cuba as the chief goal in a plan to make the Caribbean part of a slavery empire. That filed, and the Spanish colonies, such as Cuba and Puerto Rico, remained in Spain?s grasp. This seemed to many Americans a violation of the Monroe Doctrine.From 1895?1898, a violent conflict in Cuba developed and captured the attention of Americans because of the economic and political instability that it produced. The long-held U.S. interest in ridding the Western Hemisphere of European colonial powers and American public outrage over brutal Spanish tactics created much sympathy for the Cuban revolutionaries in the 1890s. By early 1898, tensions between the United States and Spain had been mounting for months. After the U.S. battleship Maine exploded and sank in Havana harbor under mysterious circumstances on February 15, 1898, U.S. military intervention in Cuba became likely.On April 11, 1898, President William McKinley acted, and asked Congress for authorization to end the fighting in Cuba between the rebels and Spanish forces, when clearly meant American intervention, and to establish a ?stable government? that would ?maintain order? and ensure the ?peace and tranquility and the security? of Cuban and U.S. citizens on the island. On April 20, the U.S. Congress passed a joint resolution that acknowledged Cuban independence, demanded that the Spanish government give up control of the island, foreswore any intention on the part of the United States to annex Cuba, and authorized McKinley to use whatever military measures he deemed necessary to guarantee Cuba?s independence.The Spanish government rejected a U.S. ultimatum and immediately severed diplomatic relations with the United States. McKinley responded by implementing a naval blockade of Cuba on April 22 and issued a call for 125,000 military volunteers the following day. That same day, Spain declared war on the United States, and the U.S. Congress voted to go to war against Spain on April 25.The future Secretary of State John Hay described the ensuing conflict as a ?splendid little war.? The first battle was fought on May 1, in Manila Bay, where Commodore George Dewey?s Asiatic Squadron defeated the Spanish naval force defending the Philippines. The Spanish Caribbean fleet under Adm. Pascual Cervera was located in Santiago harbor in Cuba by U.S. reconnaissance. An army of regular troops and volunteers under Gen. William Shafter (including future president Theodore Roosevelt and his 1st Volunteer Cavalry, the ?Rough Riders?) landed on the coast east of Santiago and slowly advanced on the city in an effort to force Cervera?s fleet out of the harbor. On June 10, U.S. troops landed at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba and additional forces landed near the harbor city of Santiago on June 22 and 24. On July 1 took place the Battle of San Juan Hill, victory in which boosted the Rough Riders and their leader Roosevelt into instant fame. On the naval front, after isolating and defeating the Spanish Army garrisons in Cuba, the U.S. Navy eyed the Spanish Caribbean squadron on July 3 as it attempted to escape the U.S. naval blockade of Santiago. In the ensuing battle all of his ships came under heavy fire from U.S. guns and were beached in a burning or sinking condition. Santiago surrendered to Shafter on July 17, thus effectively ending the brief but momentous war.On July 26, at the behest of the Spanish government, the French ambassador in Washington, Jules Cambon, approached the McKinley Administration to discuss peace terms, and a protocol - to end hostilities - was signed on August 12. President McKinley then issued Proclamation 422?Suspension of Hostilities with Spain, which stated ?The United States and Spain have formally agreed upon the terms on which negotiations for the establishment of peace between the two countries shall be undertaken; and Whereas it is in said protocol agreed that upon its conclusion and signature hostilities between the two countries shall be suspended and that notice to that effect shall be given as soon as possible by each Government to the commanders of its military and naval forces: Now, therefore, I, William McKinley, President of the United States, do, in accordance with the stipulations of the protocol, declare and proclaim on the part of the United States a suspension of hostilities and do hereby command that orders be immediately given through the proper channels to the commanders of the military and naval forces of the United States to abstain from all acts inconsistent with this proclamation.?In those days for a proclamation to take effect the president had to sign an order that the Great Seal of the United States be affixed to the proclamation. Only then could it become law. McKinley?s proclamation ending hostilities was no excep

A letter last sold more than 30 years agohttps://vimeo.com/947544603?share=copy?In 1832 Samuel FB Morse, a professor of painting and sculpture at the New York University, became interested in the possibility of electric telegraphy and made sketches of ideas for such a system. In 1835 he devised a system dots and dashes to represent letters and numbers. This was Morse Code. In 1837 he was granted a patent on an electromagnetic telegraph. Morse?s original transmitter incorporated a device called a portarule, which employed molded type with built-in dots and dashes. The type could be moved through a mechanism in such a manner that the dots and dashes would make and break the contact between the battery and the wire to the receiver. The receiver, or register, embossed the dots and dashes on an unwinding strip of paper that passed under a stylus. The stylus was actuated by an electromagnet turned on and off by the signals from the transmitter. Thus did the telegraph work.The first demonstration of the system by Morse was conducted for his friends at his workplace in 1837. There were other demonstrations in the years to come.In 1838, Morse formed a company around his telegraph invention. His business objective was to patent and demonstrate electronic telegraph service, and sell the invention to the United States Government, which would then construct a telegraph network operated by the incumbent communications network, the Post Office. They began lobbying Congress to finance the concept.In 1842 Members of Congress witnessed the sending and receiving of messages over part of the telegraph line between two committee rooms. Congress was interested, and Hon. John P. Kennedy introduced an "Act to Test The Practicability of Establishing a System of Electro-Magnetic Telegraphs by The United States?, and which appropriated $30,000 to Morse under the direction of the Secretary of the Treasury to build an experimental network.In March 1843, Congress acted to authorize the telegraph and provide funds to build it. It passed an ?Act to Test The Practicability of Establishing a System of Electro-Magnetic Telegraphs by The United States?, which provided, ?Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the sum of thirty thousand dollars be, and is hereby, appropriated out of any moneys in the treasury not otherwise appropriated, for testing the capacity and usefulness of the system of electro-magnetic telegraphs invented by Samuel F. B. Morse, of New York, for the use of the Government of the United States, by constructing a line of said electro-magnetic telegraphs, under the superintendence of Professor Samuel F. B. Morse, of such length, and between such points, as shall fully test its practicability and utility and that the same shall be expended, under the direction of the Secretary of the Treasury, upon the application of said Morse?And be it further enacted, that the Secretary of the Treasury be, and he is hereby, authorized to pay, out of the aforesaid thirty thousand dollars, to the said Samuel F. B. Morse, and the persons employed under him, such sums of money as he may deem to be a fair compensation for the services of the said Samuel F. B. Morse, and the persons employed under him, in constructing and in superintending the construction of the said line of telegraphs authorized by this act. Approved March 3, 1843.?U.S. Postmaster General Charles A. Wickliffe was in overall charge of the line and Morse was made superintendent with operational authority. Wire began to be laid in Baltimore on October 21, 1843.In his original proposal for the telegraph, Morse had elected to run the cable underground, which necessitated a large amount of lead pipe. He originally contracted with James E. Serrell to deliver the necessary quantity. But by Fall of 1843, as the line progressed, Serrell could not produce pipe quickly enough. Morse revoked the contract and hired Tatham & Bros. of New York, but they too, experienced serious problems. The pipes proved defective in large part and Morse wrote to family and close friends of his fear for the project. FO Smith was the contractor tasked with delivering the pipe. An assistant, Prof. Fiskee, had been left in charge of monitoring the quality and delivery of this while Morse was back and forth between DC, Baltimore and New York, his primary residence.By December 20, in light of these difficulties and his concern for the process, he hoped to complete in the line in Spring. Morse made the decision to pause for the winter, so he would have the tine to spend the coming weeks handling the delicate negotiations in Washington, his vendors, as well as charting a way forward, all in a short period of time. He wrote to Louis McLane, President of the B&O Railroad, "I have thought it best to discontinue operations along the line for the winter, confining myself to Washington in arranging for the Spring.?As part of establishing himself in his "winter quarters,? so that the telegraph could move forward, he wrote this very letter to William Jones, the post master in Washington DC, to inform him that he [Morse] was superintendent of the telegraph and required to set up an account to handle the correspondence generated by the telegraph. Autograph letter signed, January 1, 1844, Washington, to Jones. ?As I shall be receiving and sending letters daily, relating to the magnetic telegraph of which I am superintendent, I wish to open an account with you as Post Master for such postage and request that you render to me a monthly bill as Superintendent of Magnetic Telegraphs. Letters from me will be endorsed on the face ?charge SJ Morse, Supt. Maj. Tel.?In light of difficulties with the pipe, Morse decided to abandon the underground wire plan and turned to stringing his wire on poles, which would ultimately prove successful. On 24 May 1944, tapping a key in his Washington D.C. terminus, he transmitted the first message over the

Ephraim Putnam of Middlesex County, Massachusetts, on May 3, 1737. He was active throughout the American Revolution. He was a Minute Man on April 19, 1775, and arrived at Concord as the battle was ending. He was a soldier throughout the Revolutionary War, served at Bunker Hill, was with Washington crossing the Delaware, at the encampment at Valley Forge, and was present at Cornwallis? surrender in 1781. It is said of him that few men took a more active part in the struggle which secured the independence of the American colonies.?John Hancock was the first governor of Massachusetts and the first man to sign the Declaration of Independence. He then served as a delegate and president of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress in 1773, was a member of the Continental Congress from 1775 to 1880, served as president of the Continental Congress from 1775 to 1777, and was a member of the Massachusetts Constitutional Convention in 1780. He also served as governor of Massachusetts from 1780 to 1785 and 1787 to 1789.Document signed by Hancock as governor of Massachusetts, Boston, June 14, 1790, naming Warren an Ensign in the Massachusetts militia, and stating to him that he should ?discharge the duties of an Ensign in leading, ordering and exercising said company in arms.? On the verso, a clerk writes ?Middlesex, October 5, 1790. The within named Ensign Warren appeared and took the oath required by the Constitution.? The document is countersigned by John Avery, Jr., Secretary of the Commonwealth. Affixed to a light board.An uncommon Hancock military appointment for a great soldier of the Revolution.

This proclamation is the first Reconstruction measure we have seen reach the market, and shows the efforts Grant and Northern supporters took to protect the freedmenIt is not widely known that Ulysses S. Grant was in sympathy with the freed African Americans and very much unsympathetic to racists that sought to keep them down. This being the case, he faced numerous civil rights challenges during his presidency. The transition to Reconstruction under the leadership of his Republican Party altered the direction of the country, especially the lives of African Americans. The 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments ended slavery, extended US citizenship to African Americans with equal protection under the law, and established voting rights for African American men. Black Americans also attended school, established their own churches, becoming politically active, and held political offices at the local, state and federal level. As these dramatic changes were taking place throughout southern society, many white Southerners resented this newfound independence among African Americans and rejected the Republican Party that was promoting all this change. Some turned towards violence to maintain white supremacy and topple Republican rule in the south. As President, and as a sympathizer with the former slaves, Grant needed to find ways to curb this violence.The most well-known violent white supremacist group to form during this period was the Ku Klux Klan. It was formed in Pulaski, Tennessee in 1866 and as the Klan spread throughout the South, its members? intentions became more sinister and violent. KKK members attacked freed people exercising their new rights as well as whites who supported the Republican Party. Their methods included burning Black schools and churches, intimidating Black and Republican voters, and even resorting to rape and murder. KKK members often wore ghoulish disguises and committed their crimes at night, terrifying their victims. Worse, the Klan?s goals were supported by many local officials as well as law enforcement, which meant that Klan violence was rarely prosecuted at the local or state level. Klan activities threatened to undermine federal reconstruction efforts in the former Confederacy. Therefore, Republican governors and officials appealed to President Grant for help if local and state authorities were unable or unwilling.President Grant looked at the violence with increasing concern. He had a genuine regard for the well-being of the freed people who had supported the Union in large numbers and was concerned that the actions of the Ku Klux Klan were undermining the verdict of the Civil War. Grant was determined to do something. In a letter to Speaker of the House James G. Blaine, Grant wrote, ?there is a deplorable state of affairs existing in some portions of the south demanding the immediate attention of Congress. If the attention of Congress can be confined to the single subject of providing means for the protection of life and property in those sections of the Country where the present civil authority fails to secure that end, I feel that we should have such legislation.?Congress responded with three ?Force Acts? aimed at stopping the violence, especially by the Ku Klux Klan. The Enforcement Act of May 1870 prohibited ?banding together? or ?going in disguise upon the public highways or upon the premises of another? to violate a citizen?s constitutional rights. As the Klan was known for their disguises, this act called put them on notice. The Second Force Act of February 1871 put federal elections under federal supervision mainly by federal judges and U.S. Marshals. Finally, the Third Force Act of April of 1871 empowered President Grant to suspend Habeas Corpus and use the military to enforce these acts. The latter two Force Acts were also known as the ?Ku Klux Klan Acts.?Grant didn?t waste much time. On May 3, 1871, he issued a proclamation warning that terroristic acts of violence would not be tolerated by his administration. Grant tried to appeal to the people of the South. ?I do particularly exhort the people of those parts of the country to suppress all such combinations [lawlessness] by their own voluntary efforts,? Grant remarked, ?and to maintain the rights of all citizens of the United States and to secure to all such citizens the equal protection of the laws.? Continuing, the President warned that ?I will not hesitate to exhaust the powers thus vested in the Executive, whenever and wherever it shall become necessary to do so for the purpose of securing to all citizens of the United States the peaceful enjoyment of the rights guaranteed to them by the Constitution and laws.?Grant decided to make an example of several areas in the South, where some of the worst violence and lawlessness was taking place. After the Klan in those areas failed to heed Grant?s warning, he utilized the Third Force Act. President Grant suspended habeas corpus (the right of a detained person to request help from a court to determine if their imprisonment is lawful) and would soon declare martial law in nine mostly upstate South Carolina counties. Detachments of the 7th U.S. Cavalry were stationed in the area and worked to gather information and intelligence on local Klan activities. The military and US. Marshals then rounded up suspected Klan members for trial. The military worked with the Department of Justice and Grant?s Attorney General, Amos Akerman, to prosecute KKK members suspected of engaging in terroristic violence. The Justice Department aimed to protect the rights of newly-freed African Americans and serve as the federal government's enforcement mechanism for the various laws described above.These efforts had mixed success. During the period of martial law, many Klan members went into hiding or fled. Federal resources were thin and Grant?s political adversaries?both North and South?railed against the alleged overreach of federal power as a violation of federalism. Issues of st

His work on behalf of Dutch interests that year cut to the heart of foreign ownership of American land?This ?would enable me to do it [settle the amounts] with greater correctness & propriety??The history of Western New York?s European settlement is fraught with interconnected events and relationships, including some between several well-known characters.LeRoy, Bayard, and McEvers were partners in a New York City mercantile firm which represented the Holland Land Company in the United States. The Company was a group of six Dutch banking firms which formally organized as the Holland Land Company on February 13, 1796. Alexander Hamilton worked with the land company and would have assisted the firm LeRoy, Bayard, and McEvers, the Company's agent, in his capacity as their attorney.Robert Morris acquired approximately four million acres of land in New York which he had obtained from Massachusetts in 1791. The Massachusetts claim to these lands, which went back to the 1620 charter of the Plymouth Company, was settled in 1786 by an agreement between Massachusetts and New York. Under this agreement, Massachusetts was given the preemption rights (that is, the right to purchase the title to the land from the Native Americans), while New York was given all governmental rights over the lands in question. Thus, in 1791, Morris purchased not the land but rather the right of Massachusetts to deal with the Native Americans for this land. Morris sold about 3.6 million acres of this tract to the Holland Land Company. The company retained ?37,500 of the purchase money until Morris secured the title and completed the necessary surveys.From 1791 to 1795, warfare prevented any final settlement of land rights, and in 1795, when peace was restored by the Treaty of Greenville, Morris lacked the necessary funds to treat with the Native Americans. Accordingly, the Holland Land Company advanced him ?9,000 out of the ?37,500 retained to begin the negotiations. The Holland Land Company desired the treaty, for it could not sell the lands purchased from Morris until the former title had been extinguished. Morris wanted the Native Americans to relinquish their title so that he could use his lands west of the Holland Land Company?s purchase to secure or pay some of his numerous debts.Negotiations with the Seneca tribe began on August 28, 1797, and an agreement was signed on September 15, 1797. Morris, who did not attend the negotiations, was represented by his son Thomas. The Native Americans agreed to sell to Morris the lands in question (except for some reserved lands or reservations) for one hundred thousand dollars, which was to be invested in stock of the Bank of the United States. The treaty, or more accurately, the agreement, is entitled ?Contract entered into, under the sanction of the United States of America, between Robert Morris and the Seneca Nations of Indians.?However, an obstacle remained. The American firm was holding the land on behalf of the foreign owners. New York followed the common practice of not allowing foreigners to hold unencumbered title to land in the new country.Th?ophile Cazenove was a native of Holland and had a brokerage and commercial business in Amsterdam from 1763-1788. He represented the ?Six Houses? (Dutch banking houses) in their American business. He arrived in the United States in 1790 and persuaded the banks to invest in western lands. Between 1792 and 1794, Cazenove purchased more than five million acres in western New York and Pennsylvania for his employers. Both Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr advised him on matters of his clients? land and interests in America.Determined to make an all-out effort to mobilize support in the legislature to eliminate all restrictions on land tenure, Mr. Cazenove, who was negotiating on behalf of the Holland Company, asked help from Aaron Burr. A key member of the New York State Legislature in 1797, Burr agreed to help him. So well did Burr succeed that on April 2, 1798, the legislature passed the Alien Land Holding Act that permitted foreigners to own land in the State of New York "forever." Hamilton was also advising them, as we see from correspondence showing the American firm's work contracted out to both men, Burr and Hamilton, in May of that year.So by the end of 1798 the matter was settled, with the Holland Land Company and its U.S. representative LeRoy, Bayard, and McEvers satisfied with the results. Alexander Hamilton set about doing his end of the year accounting, including funds paid him in fees and a determination if any sums were still owing. He wrote LeRoy, Bayard, and McEvers asking for confirmation of his account.Autograph letter signed, New York, December 26, 1798, addressed to the firm of Messrs. Le Roy, Bayard, and McEvers. ?Gentlemen, I am making out your account to the end of the present year. It would enable me to do it with greater correctness & propriety if you could furnish me with a memorandum of the sums you have from time to time paid me as fees & the objects. Excuse this trouble. Yrs with true affection?A Hamilton.?The Papers of Alexander Hamilton note this letter as not having been found.Hamilton was busy with other things as well. In 1798, during the XYZ affair against France, Hamilton returned to the army in July 1798 with the rank of major general. He served as the inspector general and was second in command to George Washington. As Washington was stationed at Mount Vernon at this time with no desire to leave his beloved home, Hamilton was essentially in charge of the United States military.An interesting letter associating Hamilton with Robert Morris and the land in the west the settlers were obtaining from the Native Americans.

"I regret above all the state of the public spirit in a country in which I have seen such zeal for the cause of liberty, and in which the zeal was so often pushed to such exaggeration that it afflicted its true friends"?A powerful summation of his hopes for a peaceful freedom in democratically aspiring countriesIn 1824 the United States was in the midst of the Era of Good Feelings, was growing and progressing, and seeing a brilliant future. At the same time the generation of the Founding Fathers and Mothers who had created the republic was passing from the scene; the memory of their deeds and their ideals was growing dim, even as their grandchildren enjoyed the benefits of their labors. So the nation was looking forward and backward at the same time. Lafayette was the last surviving general of the Revolution, and although neglected in Europe, the story of his gallantry during that war, his wounds suffered at the Battle of Brandywine, his Virginia campaign that forced Lord Cornwallis into Yorktown, his relationship with the beloved Washington, were all part of the American legend. President Monroe invited him to visit the U.S. He accepted, and his 1824-5 visit to the United States became one of the landmark events of the first half of the 19th Century in America. For those who had been involved in that fight?the Revolutionary officers and those of the Society of the Cincinnati and similar organizations?the visit of their old chief would be the occasion to again light the torch just in time to pass it to a new generation. For their progeny, it would be the chance to bid a symbolic farewell to the fading, revered generation of the Revolution.While Lafayette was returning to France, Louis XVIII died, and Charles X took the throne. As king, Charles intended to restore the absolute rule of the monarch, and his decrees had already prompted protest by the time Lafayette arrived. Lafayette was the most prominent of those who opposed the king. In the elections of 1827, the 70-year-old Lafayette was elected to the Chamber of Deputies again. Unhappy at the outcome, Charles dissolved the Chamber, and ordered a new election: Lafayette again won his seat. He was popular enough that Charles felt he could not be safely arrested, but Charles? spies were thorough: one government agent noted ?his [Lafayette?s] seditious toasts ? in honor of American liberty?.On March 17, 1830, the majority in the Chamber of Deputies passed a motion of no confidence, the Address of the 221, against the king and Polignac's ministry. The following day, Charles dissolved parliament, and alarmed the opposition by delaying elections for two months. During this time, the liberals championed the "221" as popular heroes, while the government struggled to gain support across the country, as prefects were shuffled around the departments of France. The elections that followed, taking place between July 5 and 19, 1830, and returned a narrow majority for Polignac and his Ultra-royalists, but many Chamber members were nevertheless hostile to the king.Among the men sympathetic to the cause of liberty were Toussaint Borely, President of the Court of Appeals in the Southern French cultural center of Aix-en-Provence, and a candidate for the representative in the chamber representing the South, M. Thomas.However, as much desirous of the freedoms associated with representation, justice, and press freedoms, Lafayette feared the anarchy and chaos he had seen before in the French Revolution, the overthrow of the monarchy that led to bloodshed and a generation of war.Letter Signed, La Grange, July 3, 1830, to Toussaint Joseph Bor?ly, Preident of the Court of Appeals in the Southern French town of Aix-en-Provence. "The details you give me are certainly side, my dear President; I thank you nonetheless for having communicated them to me. I regret the situation with our colleague Mr. Thomas, all while hoping that he will be able to be nominated elsewhere; but I regret above all the state of the public spirit in a country in which I have seen such zeal for the cause of liberty, and in which the zeal was so often pushed to such exaggeration that it afflicted its true friends. We must hope that your beautiful region will repose itself one day in the true principles and veritable practice of this legal liberty, which in the end will triumph. Offer to my dear old colleague and received yourself the expressions of my sentiments which I offer with all my heart."On July 25, 1830, the King signed the Ordinances of Saint-Cloud, removing the franchise from the middle class and dissolving the Chamber of Deputies. The decrees were published the following day. On July 27, Parisians erected barricades throughout the city, and riots erupted. In defiance, the Chamber continued to meet. When Lafayette, who was at La Grange, heard what was going on, he raced into the city, and was acclaimed as a leader of the revolution. When his fellow deputies were indecisive, Lafayette went to the barricades, and soon the royalist troops were routed. Fearful that the excesses of the 1789 revolution were about to be repeated, the deputies made Lafayette head of a restored National Guard, and charged him with keeping order. The Chamber was willing to proclaim him as ruler, but he refused a grant of power he deemed unconstitutional. He also refused to deal with Charles, who abdicated on August 2. Many young revolutionaries sought a republic, but Lafayette felt this would lead to civil war, and chose to offer the throne to the duc d?Orleans, Louis-Philippe, who had lived in America and had far more of a common touch than did Charles. Lafayette secured the agreement of Louis-Philippe, who accepted the throne, to various reforms.

In 1812, Napoleon was still at the height of his fortunes. The Peninsular War against Britain was a thorn in the side of his great European empire, but he was confident that his generals would soon triumph in Spain. All that remained to complete his ?Continental System??a unilateral European blockade designed to economically isolate Britain and force its subjugation?was the cooperation of Russia. After earlier conflict, Napoleon and Czar Alexander I kept a tenuous peace, but the Russian czar was unwilling to submit to the Continental System, which would be ruinous to the Russian economy. To intimidate Alexander, Napoleon massed his forces in Poland in the spring of 1812, but still the czar resisted.On June 24, Napoleon commenced his famed campaign in Russia, ordering his Grande Arm?e, the largest European military force ever assembled to that date, into Russia. The enormous army featured more than 500,000 soldiers and staff and included contingents from Prussia, Austria, and other countries under the sway of the French empire. The campaign would be characterized by the massive toll on human life: in less than six months Napoleon lost near half of his men because of the extreme weather conditions, battle, disease and hunger. On both sides, nearly a million soldiers and civilians died.Napoleon?s military successes traditionally lay in his ability to move his armies rapidly and strike quickly, but in the opening months of his Russian invasion he was unable to move with speed, and was instead forced to be content with a Russian army seemingly in perpetual retreat. The fleeing Russian forces adopted a ?scorched earth? strategy, seizing or burning any supplies that the French might pillage from the countryside. Meanwhile, Napoleon?s supply lines became overextended as he advanced deeper and deeper into the Russian expanse. The Battle of Smolensk was the first major battle of the French invasion. It took place on 16?18 August 1812.Many in Russia were critical of the Russian army?s refusal to engage Napoleon in a more direct confrontation. Under public pressure, in late August Alexander named General Mikhail Kutuzov supreme commander in August, but initially the veteran of earlier defeats against Napoleon continued the retreat. Finally, Kutuzov agreed to halt at the town of Borodino, about 70 miles west of Moscow, and engage the French. The Russians built fortifications, and on September 7 the Grande Arm?e attacked. Napoleon was uncharacteristically cautious that day; he didn?t try to outflank the Russians, and he declined to send much-needed reinforcements into the fray. The result was a narrow but decisive victory. There Kutuzov decided not to defend Moscow but to launch a general withdrawal to save the Russian army.Napoleon was sure that once Moscow was taken Alexander would be forced to capitulate. On September 14, the French entered Moscow, only to find it abandoned. All but a few thousand of the city?s 275,000 people were gone. Napoleon retired to a house on the outskirts of the city for the night, but two hours after midnight he was informed that a fire had broken out in the city. He went to the Kremlin, where he watched the flames continue to grow. Reports began to come in telling of Russians starting the fires and stoking the flames. Suddenly a fire broke out within the Kremlin, apparently set by a Russian military policeman who was immediately executed. With the firestorm spreading, Napoleon and his entourage were forced to flee down burning streets to Moscow?s outskirts and narrowly avoided being asphyxiated. When the flames died down three days later, more than two-thirds of the city was destroyed. The images of Moscow on fire are iconic; many great works of art depict the event.After waiting a month for a surrender that never came, Napoleon was forced to lead his starving army out of the ruined city. Suddenly, Kutuzov?s army appeared and gave battle on October 19 at Maloyaroslavets. The disintegrating Grande Arm?e was forced to abandon the fertile, southern route by which it hoped to retreat and proceed back along the ravaged path over which it had originally advanced. During the disastrous retreat, Napoleon?s army suffered continual harassment from the merciless Russian army. Stalked by hunger, subzero temperatures, and the deadly lances of the Cossacks, the decimated army reached the Berezina River late in November, near the border with French-occupied Lithuania. However, the river was unexpectedly thawed, and the Russians had destroyed the bridges at Borisov.Napoleon?s engineers managed to construct two makeshift bridges at Studienka, and on November 26 the bulk of his army began to cross the river. On November 29, the Russians pressed from the east, and the French were forced to burn the bridges, leaving some 10,000 stragglers on the other side. The Russians largely abandoned their pursuit after that point, but thousands of French troops continued to succumb to hunger, exhaustion, and the cold. In December, Napoleon abandoned what remained of his army and raced back to Paris. He had to travel incognito across Europe with a few cohorts and reached the capital of his empire on December 18. Six days later, the Grande Arm?e finally escaped Russia, having suffered a loss of more than 400,000 men during the disastrous invasion. Napoleon?s invasion of Russia became a byword for failure and in time led to his overthrow.Letter signed, Moscow, September 28. 1812, to Jean-Jacques R?gis de Cambac?r?s, his trusted advisor who was constantly consulted for advice. "My cousin. I have received your letter of the 12th. We have nothing new here. On this I pray that God has you in His holy and worthy guard."

With only 8 days to go before the 1892 presidential election Cleveland was the consummate politician. He had lost his previous re-election bid in 1888 to Benjamin Harrison but came back to win in 1892, becoming the only president to serve two separate terms.Autograph letter signed, two pages, New York, October 31, 1892, just eight days before the election, to Donald Dickinson, almost surely his former Postmaster General Donald M. Dickinson, head of the Michigan delegation to the Democratic National Committee in 1892 who had helped secure Cleveland?s first nomination eight years before. ?I am sorry the committee has reached the conclusion you announce. I don't guess and I don't think but I know it is a mistake for me to speak anywhere up to tomorrow night. With such a settled conviction on my mind you cannot shame me if I only partly agree with the committee. If it is invited me I will go to Jersey City next Friday evening if a meeting is to be held there. That is all I can do. I am half sick and have an all night job before me. I wish the committee could see the matter differently. If I go the responsibility must be on them.?It seems clear that Cleveland was tired and overworked by the end of the 1892 campaign, and felt the need to limit his campaigning. He won the election held just eight days after he wrote this letter.

The U.S. Constitution meant a great deal to John F. Kennedy, and he spoke of it often?During the 1960 presidential election campaign, Democratic nominee John F. Kennedy articulated his long-held feelings about the U.S. Constitution. In July, he said ?You have, at the same time, placed your confidence in me, and in my ability to render a free, fair judgment - to uphold the Constitution and my oath of office.?In September, he wrote of the principle on which the Constitution was founded: ?The greatness of our Constitution comes not so much from the words that it contains. It is great because of the people who have lived and worked under it to add to its framework of words and ideas the work and sacrifice and passionate devotion of many generations of Americans. Men and women came here from every corner of the world, from every nation and every race to live together as parts of one great, unified nation. Our Constitution is founded on the principle that all men are equal as citizens, and entitled to the same rights, whether they achieved citizenship by birth, or after coming here as immigrants, seeking to find in America new freedom and new opportunities.?On October 12, in New York, he spoke at the National Conference on Constitutional Rights and American Freedoms, and said, ?Freedom is indivisible, too, in all its aspects. To provide equal rights for all requires that we respect the liberties of speech and belief and assembly, guaranteed by the Constitution, and these liberties in turn are hollow mockeries unless they are maintained also by a decent economic life. That is why Franklin Roosevelt linked freedom from want and freedom from fear with freedom to believe and freedom to speak. Those who are too poor, uninformed, too uneducated to enjoy their constitutional freedoms of choice, do not really possess those freedoms. That is why we fight so hard for minimum wage legislation, for better housing, for social security protection in illness in old age. In order to participate in the other great freedoms we have to have a standard of living for our people so that they can enjoy them.?After he became president, in 1962, he told Congress ?Members of the Congress, the Constitution makes us not rivals for power but partners for progress. We are all trustees for the American people, custodians of the American heritage. It is my task to report the State of the Union - to improve it is the task of us all.?Also in 1962, he stated, ?For in a government of laws and not of men, no man, however prominent or powerful, and no mob however unruly or boisterous, is entitled to defy a court of law. If this country should ever reach the point where any man or group of men by force or threat of force could long defy the commands of our court and our Constitution, then no law would stand free from doubt, no judge would be sure of his writ, and no citizen would be safe from his neighbors.??The Constitution?, containing the original Constitution plus the Amendments to that date, inscribed and signed ?To David Healy & Theresa, with very best wishes, Congressman John Kennedy.? Obtained at a speaking engagement in Columbia Park in South Boston by a college student in the early 1950s, and obtained by us from his descendants. It has never been offered for sale. The pages were originally part of a larger book, which comes with it. It is intact as a separate textual unit.The only copy of the U.S. Constitution signed by JFK that we have ever seen. This series of pages was originally a stand-alone, opening section of a book on ?Readings in American History?.