LINSCHOTEN, Jean Hugues

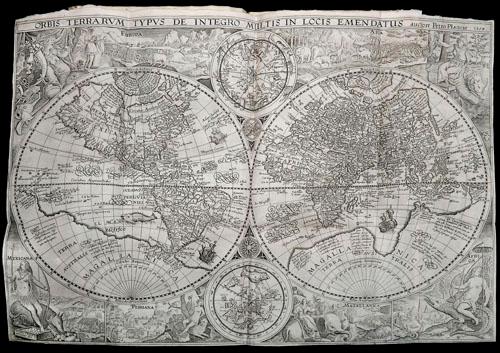

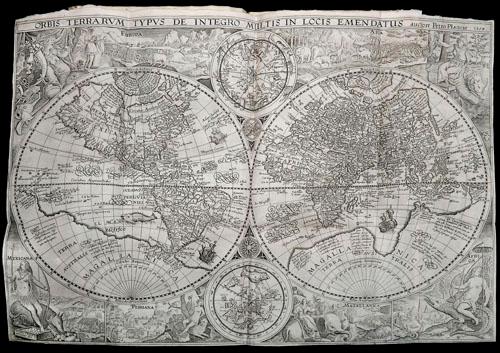

Amsterdam, Evert Cloppenburgh, 1638. Folio [20 x 30.5 cm], (4) ff. [including half-page engraved portrait on verso of 4th preliminary leaf], 206 pp.; (2) ff. [including second engraved title], 181 pp.; (1) f. [third engraved title], 1-60; 67-86 [i.e., 79] pp., 36 plates and 6 maps. Bound in contemporary vellum over pasteboards, edges of covers frayed and corners exposed; blank right corner of title and of preliminaries slightly dog-eared, some leaves a bit dusty; but generally an exceptionally fresh, altogether unsophisticated copy. Excellent. The preferred large format French language 3rd edition. This is a large and absolutely genuine example of this classic illustrated travelogue to the East and West Indies, termed by Lach the most important of the firsthand accounts published independently of the great travel collections (I.198). No other book contained so much practical intelligence on the East and West Indies as Linschoten's. Unhindered by the censorship that affected writers from the Iberian Peninsula, the author included such information as sailing directions, physical descriptions of countries, and statistics on commerce and trade. The work was held in such high regard that for nearly a century, every Dutch ship headed for the East carried a copy of a Dutch edition of Linschoten. This copy of the third French edition (esteemed for its plates; see below) is rather unusual for being in an entirely contemporary condition in its original binding, and entirely unsophisticated internally. Although the work contains valuable reconnaissance for the New World (see below), the material on the East Indies is far and away the most valuable, being the fruit of the author's own observation. In the service of the Portuguese, Linschoten spent five years in Goa (1583-88/9), making numerous visits to the mainland. He was thoroughly immersed in Indian culture and the complex relations between the Portuguese colonial apparatus and indigenous peoples. Highlights include a first-hand descriptions of the caste system, political structures, business practices of the Banyas, and exotic natural phenomena. The first book treats the East Indies and East Africa, including regions as far east as Japan. The second book describes the navigation of the coasts of West Africa around the Cape of Good Hope to Arabia, together with the coasts of the New World, and includes a real roteiro after the Portuguese royal pilot Diego Affonso that sets out sailing directions from Portugal to India and from island to island in the East Indies. The third book is devoted to North America (Florida), the Caribbean and Brazil. The work was first published in Dutch in 1595/6. Latin and English translations followed in 1598. The first French edition appeared in 1610, but the plates are copies of the reduced version based on those in the De Bry; the second and third French editions return to the original, folio-sized plates of the Dutch edition and are accordingly the most desirable. * Borba I, 490; Alden/Landis 638/37; Tiele 686-88; Lach, Asia in the Making of Europe, 1.1.196-204 & 482-90; Burnell & Tiele, The Voyage of John Huyghen van Linschoten to the East Indies, Hakluyt Society (Old Series) LXX-LXXI (London 1885).

POLO, Marco

[10], 123, [1] ff. (printer's device on verso). Bound in modern red crushed morocco, raised bands, spine in six compartments, spine gold tooled and lettered, covers blind tooled, gold-tooled board edges, gold-tooled dentelles, blue ribbon bookmark, red sprinkled edges. Only very minor rubbing corners, bookplate inside upper cover. Title a bit dusty, inscription on title ("Masson"), minor pale spotting to first few leaves, a few minor marginal stains, contemporary signature to f. 80 ("Didier Langreve"?), verso of final leaf a bit dusty. Rare first French edition of the work considered "the first to give anything approaching a correct and detailed account of China and the Far East" (PMM), and perhaps the most influential travel book of all time. This first appearance in French should possibly be linked to topical interest in the wider world: The description of China in Münster's Cosmographia is mentioned in the preface and one should recall that the 1550s saw intensive French exploration and colonization in the Americas. "Marco Polo was a member of a prosperous Venetian family engaged in commerce. He set out with his father and uncle in 1271 on a journey to the East. Starting from Acre the party traveled through Persia and the Upper Oxus to the Pamir plateau, and then through Mongolia and the Gobi Desert to the extreme north-west of China, reaching Shantung in 1275. Here they sojourned at the court of Kublai Khan until 1292, finally arriving back in Venice, after travelling through south-east Asia and Southern India in 1295. During his stay in China Marco Polo took an active part in the administration of the country and travelled widely in the great Khan's service. He saw--or obtained knowledge of--large parts of China, northern Burma. Tibet, Japan, south-east Asia, the East Indies, Ceylon, southern India, Abyssinia, Zanzibar and Madagascar, Siberia and the Arctic" (Printing & the Mind of Man). The account was dictated by Polo while a prisoner after the Venetians lost to Genoa. The text was curiously composed in French, and circulated widely in manuscript: 138 are extant today. The first printed edition appeared even more curiously in German, but it was in the Latin edition of 1483/4 and the Italian of 1496 that it began to make a wider impact. The present edition is the work's first (printed) appearance in French and was brought out simultaneously by three different Parisian booksellers, issued with variant titles and different final leaves: the present issue, that by Vincent Sertenas, and one by Etienne Groulleau. They made a similar arrangement for a 1559 translation of Machiavelli, from which we know positively that Groulleau did the printing. * Cordier Sinica III.1977-78; Adams P-1791 (Groulleau); Printing & the Mind of Man 39 (Italian 1496); Hill p. 237 (modern edition, with cross-reference to Ramusio).

François Martin, de VITRÉ

(4) ff., 134 (i.e. 131) pp. Bound in contemporary vellum, housed in modern book box. Signature I misbound. Impeccable copy, excellent. Extremely rare first edition of the first French account of the East Indies to appear in print (cf. Lach & van Kley, III: 373), here in an impeccable copy bound in early vellum. The work is that of the French adventurer François Martin de Vitré (c. 1575-c. 1631), who, upon his return to Brittany from the East Indies in 1603, prepared this lively account at the behest of King Henry IV (1553-1610). Martin¿s narrative inspired Henry in 1604 to establish the first iteration of the French East India Company (Compagnie des Indes Orientales) with designs on exploiting the treasures described in the present work (cf. Lombard, ¿Martin de Vitré, Premier Breton à Aceh¿). Likely enlisted as ship¿s surgeon aboard the Croissant, François Martin of Vitré, along with several companions from Saint-Malo and Laval, sailed from Britanny in 1601, rounding the Cape of Good Hope in May of that year. The Croissant¿s companion ship, the Corbin, wrecked in the Maldives, but Martin eventually succeeded in reaching Ceylon and trading with the Aceh in Sumatra. Upon his return journey he was captured by the Dutch at Cape Finisterre but finally returned to France in 1603. In his preface Martin summarizes the European powers¿ incursions in the East and laments the tardiness of the French to exploit the region¿s riches: ¿This has made me deplore the defect of the French, who more than any other nation are provided with a vivacity of spirit and a formidable worthiness, but who have nevertheless languished for so long in a slumber of idleness, ignoring information on the treasures of the East Indies with which the Portuguese and Spanish have enriched themselves¿ (p. 3). In the first two sections of the work Martin gives ample space to the discussion of flora, fauna, and commercial matters relevant the regions he visits (aromatic plants, spices, crops, the elephant, rhinoceros and tiger, the crocodile, tortoise and bird of paradise, livestock, the hunt, woods, weights and measures, currency, etc.), but he also includes a great deal of anthropological detail. Evidently the stereotypical red-blooded Breton seafarer, Martin, in his chapter on the ¿habits and customs we observed during our stay in the Indies¿ (pp. 38-66) dwells mainly on women ¿ the prostitution of premarital women, their perfumes, their bathing rituals, their medicines, and their punishment for adultery. He also notes gestures of salutation (two hands together before one¿s forehead), marriage customs (¿they can marry seven wives if they have the means to support them¿), and gives detailed reports on the traditions and inner workings of both Hinduism and Islam. He notes Turkish merchants to be frequent visitors to these lands, and writes of seeing a cannon of Chinese manufacture. Martin¿s intriguing 4-page dictionary of words useful for the traveler includes a section on counting in Malagasy, the language of Madagascar. The volume also contains a brief but significant ¿dictionary¿ of the Malay language, described here as ¿Elegant and easy to learn, like Latin¿ (¿fort beau & facile a aprendre ¿ comme le latin en leurope¿). Finally, in his presumed role as ship¿s surgeon, Martin penned a third section treating scurvy, recommending among other cures the use of citrus fruits and an aqueous preparation of alum. OCLC lists only two U.S. copies of this 1604 first edition: NYPL and the Minnesota¿s Bell Library (lacking 2 prelims). The work was reprinted in 1609, and of this second edition OCLC locates U.S. copies only at Harvard and the Boston Athenaeum. * Atkinson 444; Brunet, Supl. I, 920 (citing only the second edition); cf. also Denys Lombard, ¿Martin de Vitré. Premier Breton à Aceh (1601-1603),¿ Archipel 54: 3-12 (1997).

NAIBOD, Valentin / [NABOD]

(8), 192 ff., with numerous textual woodcut illustrations. Bound in contemporary limp vellum, manuscript title on spine. Minor rubbing to binding, some wrinkling to spine. Minor browning in some quires, some minor marginal worming not affecting text, a few contemporary inscriptions in the text. Generally very good. Very rare first edition, second issue of this understudied work, ¿apparently the earliest Italian imprint to depict and discuss the Copernican system¿ (Gingerich) by the Cologne-born Professor of Mathematics at Padua. The work includes a printed diagram of the geo-heliocentric system of Martianus Capella (41r) as well as a diagram and exposition of the Copernican system (leaf 41v). The work is included in the Galileo bibliography of Cinti (no. 5) owing to the Copernican diagram. Cinti does not comment further than this, but it is interesting to speculate that the young Galileo (b. 1564), whether as a student at Pisa or a lecturer at Padua, may have encountered the Copernican hypothesis in the present work. It is not surprising that the exegesis of Copernicus would come relatively late to Catholic Italy in comparison to Protestant, German speaking countries, in light of both the establishment of the Index of Prohibited Books (1559) and the widespread efforts of the Counter-Reformation to insure doctrinal conformity in printed books. That it passed the watchful eye of the censor at all is probably due to its appearance in an unassuming astronomy primer and the somewhat hypothetical manner in which the theory is expressed. Although the impact of Naibod¿s work in Italy is difficult to assess, it is positively known that a copy of the first issue was owned by Tycho Brahe, still extant in the Clementinum in Prague, and it has been argued by the historian of astronomy Robert Westman that Tycho¿s encounter with the geo-heliocentric diagram of Martianus influenced the development of the Tychonic system. It also has been suggested that the Tycho assistant Paul Wittich was familiar with this work, and that the concept of ¿world system¿ (systema mundi) employed by Kepler, Tycho and Galileo originated with the present work. ¿In his elementary textbook of astronomy Valentin Nabod gave the system of Martianus Capella in which Mercury and Venus revolve about the sun. He added that Copernicus had taken occasion from this to make Saturn, Jupiter and Mars, and indeed everything included within the sphere of the moon, revolve about the sun as center of the universe, while the sun and fixed stars remain unmoved. Copernicus had thus ¿with so small a number of spheres¿ saved all the phenomena through the ages, as no one before him had done, with the greatest praise and admiration of the learned. Nabod then presented a figure of the Copernican system, which, as we have seen, was an unusual thing to do in an elementary textbook. He remarked that no one should be greatly offended by the movement of the earth and quiet of the sun. If, however, anyone preferred to consider the earth at rest and the sun as in motion, he could reach the same results by practically the same demonstrations, as was understood by all who knew anything about mathematics¿ (Thorndike, VI.40). Naibod (d. 1593) matriculated at Wittenberg in 1544, one year after the publication of De Revolutionibus, when the faculty included such important Copernicans as Reinhold and Melanchthon. He also wrote commentaries on the astrologer Alcabitius and on the Sphere of Sacrobosco. He acquired a certain amount of fame in the astrological literature of his own time for the rare feat of successfully predicting the day of his own death (see Thorndike VI.121). OCLC lists Huntington (Dibner), CIT, Harvard, University of Michigan, American University and University of Oklahoma. No American copy of Primarum de coelo (Venice 1573), though OCLC lists 4/5 German/Swiss copies. Cinti 5; not in Riccardi and no mention in Rose, The Italian Renaissance of Mathematics; Weil Cat.29.39 (c. 1950); Thornd

BARBÉ, Jean-Baptiste / VAN LOON, Theodoor

Single-sided engravings, (1) engraved title, (20) engravings. Unbound, fixed with small staples at top edge. Minor marginal handsoiling and spotting, small marginal holes to a few leaves, minor edge wear, light browning to a few leaves. Generally very good. Very rare first edition of a set of engravings by the Antwerp printmaker Jean-Baptiste Barbé (1578-1649) after the designs of Theodoor van Loon (c.1581-1649), a Flemish painter noted as an early stylistic follower of Caravaggio (1571-1610). The work presents bust-length portraits of the Holy Family, the Four Evangelists, and the Twelve Apostles, each set within a fancifully designed sculptural frame, with the wording of the collection¿s title ¿ Icons with their Frames (¿parergis¿)¿ emphasizing the importance of the relationship between painted image and its enclosing frame. While the strong shading of some plates recalls Caravaggio¿s tenebrism, facial types, which gaze sweetly into the distance, are perhaps more indebted to those of Guido Reni (1575-1642), who was working in Rome and at the height of his popularity around the time these engravings were produced. Each ¿icon¿ is depicted with his attribute or an instrument of martyrdom (e.g., Peter¿s keys, Luke¿s ox, Andrew¿s cross), and the frames often echo these iconographic connections (e.g., herms flanking the portrait of James the Major are dressed as pilgrims). The emphasis on framing devices here is likely related to the rise in an interest in Christian archeology that began around 1600 and greatly influenced the way venerable images were treated in the remodeling of major churches and their altarpieces: For example, Theodoor van Loon certainly would have known his countryman and exact contemporary Peter Paul Rubens¿ (1577-1640) early Roman commission to enclose the ancient Santa Maria in Vallicella icon at Chiesa Nuova in an elaborate, pictorial altar frame (1606-08). This suite of engravings by Barbé should not, therefore, be seen only as a collection of images suitable for personal devotion, but also as a thoughtful visual treatise concerning the way artists were asked to confront and re-present early Christian art and iconography in the first half of the seventeenth century. Interestingly, these engravings are prominently dedicated on their title page to Wenceslas Cobergher (1560-1634), a painter, architect, engineer, theorist of institutional pawn shops (monti di pietà), numismatist, and collaborator of van Loon who was deeply interested in Roman and early Christian antiquities and their use by contemporary artists. * Hollstein, Dutch and Flemish, vol. 1, p. 100, nos. 45-64; M. Funck, Livres belge à gravures, p. 356; I. Baldriga, et al., Theodoor van Loon: ¿Pictor ingenius¿ et contemporain de Rubens, 2011; T. Meganack, De kerkelijke architectuur van Vensel Cobergher in het light van zijn verblijf te Rome, 1998. OCLC and KVK locate copies at the National Gallery (D.C.), Clark Art Institute, BnF, and Vlaamse Erfgedbibliotheek (Antwerp).