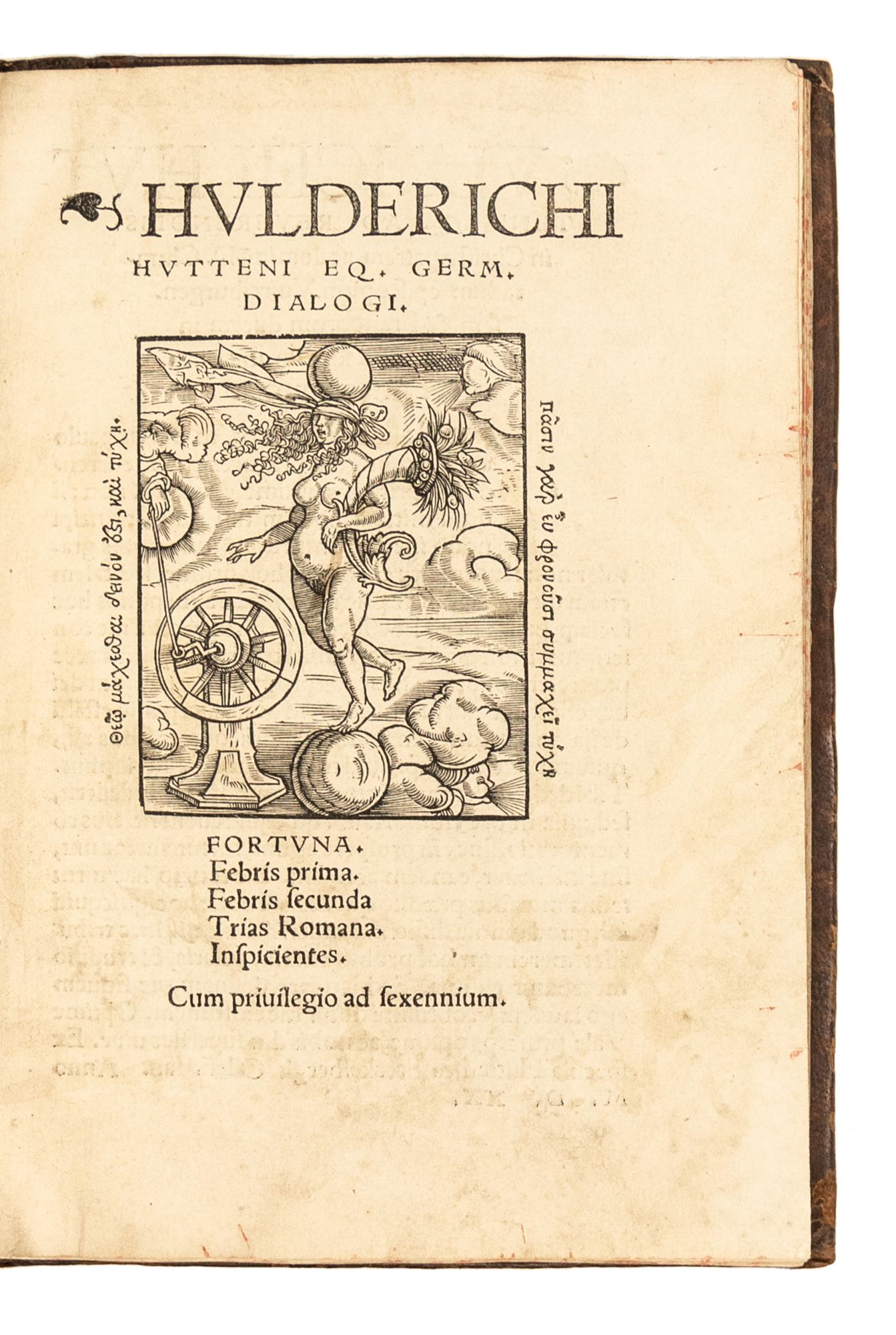

Hutten, Ulrich von (1488-1523)

Dialogi. Fortuna. Febris prima. Febris secunda. Trias Romana. Inspicientes

Johann Schöffer, Mainz: 1520

- $5,900

Bound in 17th c. calfskin, spine tooled in gold (discreet repairs to joints, corners, and top compartment of spine; slim crack at head of rear joint, minor wear to the gilding.) A nice copy with minor soiling to title and final leaf, and a few instances of light marginal foxing. With a title page allegorical woodcut of Fortuna (Fairfax Murray 215) and three attractive woodcut initials on a black ground. First edition of this important collection. Only the first "Fever" poem had appeared previously (in 1519). The anonymous German satire "Trias Romana"(1519) is a different work than Hutten's satire of the same name. The title woodcut illustrates the second (and lightest) of the five satirical dialogues, in which Hutten implores Fortune to grant him a pretty wife, a nice house with a library, children, and a reasonable income so that he can study and write. "Fever" I & II "The picture of Hutten handed down to us by history is that of the militant knight and poeta laureatus mentioned earlier. Yet in his dialogues, Hutten's positioning of his own persona is more complex and characterized by one development : the one-sided emphasis on militancy is attributed to the escalation of the Reformation controversy (evident in the Dialogi novi), whereas in the earlier dialogues deviations from this positioning are quite clear. "In the two Latin Fever dialogues (Febris prima and Febris secunda) of 1518/1519, the first dialogues in which Hutten himself appears, the author positions his own persona quite differently from his stance in the later works. In both dialogues the personified Fever attempts to invade the persona of the author in extolling to Hutten his own merits. Hutten tries to divert Fever's attention to other targets, in particular the clerics, who do not take poverty and chastity very seriously. Hutten does not limit himself to a harmless form of clerical satire; he recommends to Fever the figure of Cardinal Cajetan as a very worthwhile target. During his attendance at the Diet of Augsburg of 1518, the conduct and lifestyle of the Cardinal had offered more than enough material for satirical criticism. This polemical trait is not, however, the sole characteristic of this dialogue, which Hutten conceives in the tradition of a paradoxical encomium with his own figure being subjected to irony. "Fever tries to convince Hutten of his merits: a person beset with fever is industrious and sharp-witted and after the fever has abated, the health of the patient improves. Hutten as author can refute these claims from his own experience: when he was writing the Fever dialogues, he was undergoing the cure with Guaiacum that he had publicized in 1519 in the monograph written in that year. When the persona of Hutten declares in the dialogue that he has suffered from the aftermath of this and other diseases for many years after the fever has subsided, the author and the persona are correspondingly close. "Hutten continues with the ironic treatment of his own persona right at the beginning of the second Fever dialogue, as Fever, who was only temporarily repelled at the end of the first dialogue, now seeks even more intensive contact with Hutten. Hutten, aided by his squire, tries once again to shake Fever off. As the conversation progresses, Hutten is able to convince Fever that it is desperately needed to clean up the situation in Rome, and Fever finally leaves Hutten in peace. "The Observers" "As part of his criticism of the Church, Hutten's satire made a special target of Cardinal Cajetan, the Curia's envoy to the Diet of Augsburg in 1518. In his dialogue Inspicientes (The Observers), which appeared in 1520, Hutten has the sun god Sol and his son Phaethon observe and discuss the events in the northern hemisphere from the heavens. The two divine observers keep a careful eye on the Diet of Augsburg. At the end of the dialogue, Hutten has Cardinal Cajetan appear as the third participant in the dialogue. "In this dialogue's frenzied finale, Cardinal Cajetan vents his fury and arrogance at the sun god in the heavens and complains about the prolonged period of bad weather in Germany that is taking place contrary to his specific orders. The Cardinal threatens Sol with a ban since the god is not adhering to Cajetan's instructions and is questioning the authority of the pope. Thus, the Cardinal positions himself as being beyond the divine and human spheres and unmasks his hubris. His presumption stands in stark contrast to the positioning of Sol and Phaethon, who refer to him merely as a 'homuncio'. "Fortune" In a letter to Pirckheimer, Hutten wrote that some things are achieved on by fortune and not by virtue. "In those cases, I look for the turning of the wheel, to the blind goddess, the mad ruler, the queen of all vicissitudes. I look for a lucky turn of the wheel to bring me prosperity." In the dialogue "Fortuna", Hutten asks the goddess to grant him the means to lead a comfortable life, with leisure to study and write. "How much would be enough?" she asks. Well, Hutten answers, if he were to marry he would want a house with a garden, some land with a few fish ponds, dogs for hunting, a few riding horses, servants, herdsmen, cattle. The house must be outfitted with galleries, a library, dining rooms, baths, etc. He will also need money so that his wife can dress respectably and money to put aside for children. So, about 100,000 gulden. When Fortune advises to work instead, Hutten laments that he has worked and studied for years, wandering in exile, struggling with poverty and disease. He has tried to enrich himself at court, like other people, but has had no luck. Fortune tells him that if he wants to live a life of leisure and study, he should be content to live in poverty. After all, successful people don't have much leisure. "Do you know any?", she asks. "Priests", replies Hutten. As Fortuna casts fortune down upon the people of Earth, Hutten looks down on the scene from above and sees a mass of people scramb

More from Liber Antiquus Early Books & Manuscripts

China Monumentis Qua Sacris quà Profanis, Nec non variis Naturæ & Artis Spectaculis, Aliarumque rerum memorabilium Argumentis Illustrata, Auspiciis Leopoldi Primi Roman. Imper. Semper Augusti Munificentissimi Mecænatis

Complete with the engraved title page, a full-paged portrait of Kircher, 2 large folding engraved maps of China, 59 text engravings, and 23 full-paged engravings (one of which is a large folding reproduction of the "Nestorian Stele"), including some drawn by the artist Willem van der Laegh. This is a fine copy, bound in contemporary stiff vellum (lightly soiled.) The text and plates are crisp and mostly bright, with some light foxing or browning to scattered leaves, and a few clean tears, without loss (lvs. K2, L4, S1); natural paper irregularities to the margins of 2 plates (at p. 113 and p. 155), not affecting the image. This copy features a variant of the engraved title that states that this edition was printed at Amsterdam in 1667 "Vidua Elizei Weyerstraet", that is, by Sara Weyerstraet, widow of one of the original publishers, Elizaeus Weyerstraet (who died in late December 1666.) However, this is in fact the Antwerp counterfeit printed by Meursius in 1667, the engraved t.p. of which usually indicates Meurs and Antwerp as the publisher and place. "In 1667 the learned German Jesuit, Athanasius Kircher, published his 'China Illustrata' at Amsterdam. Gathering his materials from the works of other members of the Society, Kircher wrote one of the century's most influential treatises on China. His primary purpose was to establish the authenticity of the Nestorian monument discovered in Sian, and to that end he produced in print the original Chinese and Syriac inscriptions on the monument, the Chinese text in Romanization, and finally a Latin translation and his explication of the Chinese and Syriac texts. In addition, Kircher included a sizeable description of China and other places in Asia. For example, in a section devoted to the various routes to China and the history of Christianity in China, he sketched all the old overland routes, including that of Johann Grueber and Albert d'Orville from Agra to Peking, as well as giving a description of Tibet. He traced the activities of Christians in China from the tradition of St. Thomas to Boym's reports about the conversions at the Ming pretender's court and Adam Schall's experiences at the Ch'ing court during the K'ang-his era. Following what he thought to be the spread of idolatry from the Near East to Persia, India, and finally to East Asia, Kircher described the religions of China, Japan, and India. His extensive discussion of Hinduism and the Mogul Empire derived from the letters of Heinrich Roth (1620-68), his fellow Jesuit. There are several chapters on government, customs, geography, fauna, flora, and mechanical arts of China, and a very interesting scholarly discussion of the Chinese language, which indicates that Kircher had made considerable progress in it. There is a long Latin-Chinese dictionary, and Finally Father Johann Grueber's (1623-80) responses to a long series of questions posed by the duke of Tuscany. Kircher's volume contains several beautiful pictures taken from Chinese and Mughul originals which Grueber brought back to Europe with him in 1664." (Lach pp. 485-486) "Although the "China Illustrata" was not the product of Kircher's own experience in China, it was frequently used or cited as a source of information y later writers. Some of the information contained in it, for example the text of the Nestorian monument, Roth's description of Hindu religion, and Grueber's description of Tibet, had not appeared in print before. "Roth's contribution to Kircher's work includes a description of the ten transformations (avatars) of Vishnu and several illustrations of Indian provenance, as well as a discussion of the Sanskrit language which is illustrated with five plates presenting examples of Sanskrit writing. Roth returned to Europe in 1662 accompanied by Grueber, who with Father Albert d'Orville had journeyed overland from Peking to Agra by way of Lhasa. In the busy years after his return to Europe, Grueber evidently tried to write a description of Tibet and f his journey across the Himalayas. Apparently he never finished it. He may have sent parts of it to Kircher, however; he wrote several letters to Kircher and apparently sent him some of his sketches, all of which formed the basis for a description of Tibet and of Grueber and d'Orville's journey in the "China Illustrata"-probably Europe's earliest account of the Tibetan capital. Kircher's account also contains eleven very interesting plates made from Grueber's sketches, including one of the Dalai Lama and one of the Potala Palace in Lhasa which was frequently reproduced and served as Europe's only glimpse of Lhasa for the following 250 years."(Lach pp. 527-528) "China Illustrata'' was in many ways [Kircher's] most significant work historically, being the first publication of important documents on oriental geography, botany, zoology, religion and language. Kircher admits in the preface that his main concern was to preserve the fruits of his colleagues' efforts, collected with so much effort and privation, and sometimes at the cost of their very lives. Foremost among his sources were Johann Adam Schall; Bento de Goes, who in 1602 had left from the Jesuit station in Agra, north India, to find a land route to China and seek the fabled land of Cathay; Kircher's former pupil Martin Martini, appointed mathematician to the Chinese Imperial Court and author of 'Novus Atlas Sinensis' (1655); and the trio of intrepid explorers Johann Grueber, Michael de Boym and Heinrich Roth, who all returned to Rome in 1664. Grueber, whose return journey had taken three years, and led him through Tibet, modern Pakistan, Iran, and Turkey, was an accomplished draughts man and supplied the originals for many of 'China's' topographical engravings. Boym provided those of Chinese flora, and transcription of Chinese characters that enabled Kircher to publish the first vocabulary of the language. Roth, who traveled with Grueber, had already become adept in Sanskrit, of which he compiled a dictionary. HereEpigrammata antiquae Urbis

Mazzocchi, Jacopo (last qtr. 15th - c. 1527); Fulvio, Andrea (c. 1470-1543); Colocci, Angelo (1474-1549) Bound in 19th c. vellum (lightly soiled, endpapers renewed, text block resewn.) A very good copy with some minor interventions performed subsequent to the 19th c. rebinding: title soiled, first two leaves with repairs to the blank inner margin (far from the text), two lvs. with small adhesion scars costing a few letters, some stains in the gutter of the opening gatherings lightly washed but still visible, light damp-stain to outer corner of those same gatherings; scattered marginal damp-stains, lower corner of leaf P4 discreetly restored, no loss to the text. Leaf T5 and those in gathering [con] lightly toned, leaf [rum]2 spotted, leaf CLII with natural paper flaw costing a few letters, minor worming in lower margin of some gatherings, occ. spotting in final gatherings, lower blank corner of final leaf clipped, a few other minor blemishes. A foundational book on Roman epigraphy, Mazzocchi's "Epigrammata" is the first substantial collection of ancient Roman inscriptions to appear in print. It preserves many hundreds of inscriptions, many of them now lost, found in the churches, temples, palaces, public spaces, and -most intriguingly- in the private collections of Renaissance Rome. While printed in 1521, the seven-year privilege was granted by Pope Leo X in 1517. The book is profusely illustrated with woodcuts of important Roman monuments with their inscriptions (the arches of Septimius Severus and Constantine, the Claudian aqueduct, the Aqua Virgo, the Pantheon, the pyramidal tomb of Gaius Cestius, Hadrian's tomb, the Vatican obelisk, Trajan's column) and hundreds of type-set inscriptions, many of which are framed by elaborate woodcut borders in imitation of Roman aedicula, tombs, and funerary plaques. Among the most famous of these are the Roman Fasces from the façade of the house of Pietro Santacroce and the relief of the Three Graces (CIL VI, 548 (I)) in the house of "Paulus de Plancis", later in the collection of Cardinal Ludovico Podocatari. Now lost, the sculpture was a votive offering by a Roman woman, Batinia Priscilla, to the Nymphs, probably as protectors of infants. In his dedication, Mazzocchi thanks Mario Maffei of Volterra for his sponsorship of what seemed "like a new Academy" at his house, a place where learned men gathered to study antique statues and inscriptions. Mario and his brother Agostino Maffei, both antiquarian experts, housed an impressive library as well as a collection of sculptures and inscriptions. The collection in the Maffei courtyard and stairwell was drawn by Van Heemskerck in the 1530's. The work was compiled over a number of years, possibly with the collaboration of Maffei, Mariangelo Accursio, and Andrea Fulvio; sources include inscriptions in the houses of the great scholars Angelo Colocci, Pomponio Laeto, Ludovico Bello, and Guiliano Dati. Laeto's collection (described from folios xlii to xlvi) was housed in his house on the Quirinal Hill, where the members of the Accademia Romana, of which Laeto was the founder, met. The collection of the wealthy papal secretary and humanist Colocci, which included Roman sculptures, funerary and monumental inscriptions, coins, and many other specimens of epigraphic interest, was displayed in his garden near the Trevi fountain. Mazzocchi (or his fellow compilers) also visited the collections of the great and powerful. There are also inscriptions from the celebrated sculpture collection of the de' Rossi, which was dispersed in 1517. And on folio clviii, we find the famous "Sleeping Nymph" epigram, which is recorded as being found in the "viridario reverendissimi Cardi. S. Clementi" (possibly the garden of Cardinal Domenico della Rovere, where the inscription accompanied the sculpture of a sleeping nymph.) Mazzocchi also visited smaller collections, such as those held by the booksellers Stéphane Guillery and the obscure "Peter the Frenchman", in whose houses Mazzocchi saw and recorded inscriptions. Many of these private collections were destroyed or dispersed during the Sack of Rome in 1527 (for the destruction of Colocci's collection, we have an account by his friend Antonio Tebaldeo.) Thus, Mazzocchi's publication is an important primary resource for reconstructing -befittingly, only in a fragmentary way- those early collections of antiquities. "The nucleus of the 'Epigrammata' may be the 'epythapiorum opusculum' promised in Mazzocchi's colophon for Francesco Albertini's 'Opusculum de mirabilibus novae et Veteris Urbis Romae' (1510). The compilation and printing of the 'Epigrammata' took some years; the privilege for the work was granted on November 30, 1517. In the preliminary leaves, Mazzocchi reprints the 'De notis antiquarum litterarum of Valerius Probus.'"(Mortimer 297).Disputatio excellentium D. Doctoru[m] Iohannis Eccii & Andreae Carolostadii q(uae) cepta est Lipsi(a)e XXVII. Iunij. AN. M.D.XIX. Disputatio secunda D. Doctorum Iohannis Eccii & Andreae Carolostadii q(uae) cepit XV. Iulij. Disputatio eiusdem eiusdem d. Iohannis Eccii & D. Martini Lutheri Augustiniani q(uae) cepit IIII. Iulij

Eck, Johann (1486-1543); Luther, Martin (1483-1546); Karlstadt, Andreas Rudolff Bodenstein von (ca. 1480-1541) Bound in 19th c. drab wrappers (sunned.) The text is in fine condition, a few leaves lightly toned, title and blank verso of final leaf lightly soiled. Title with short bibliographical reference and 2 stamps (Nuremberg city library with deaccession stamp). A printed, eye-witness transcript of the Leipzig Disputation of 1519. The debate took place from June 27th to July 15th between the reformers Martin Luther (1483-1546) and Luther's Wittenberg colleague Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt (1486-1541) representing emerging "Protestant" views, and the Ingolstadt theologian Johannes Eck (1486-1543), representing Church orthodoxy. This is the first printed account of the entire debate. A notarial transcript ("protocol") of about two-thirds of the debate was printed at about the same time (see note in references) but precedence cannot be established. No other edition of the complete text appeared until 1729. "In the fateful series of events that led from Martin Luther's writing of the Ninety-Five Theses on the power of indulgences in 1517 to his condemnation at the Diet of Worms in 1521, few were more significant than the Leipzig Debate of 1519. It began as a disputation between Karlstadt and Eck on free will and grace in Christian life. When the topic turned to the authority of the church and papacy, however, Luther stepped in, with fateful consequences. At the debate, he stood in front of gathered theologians, students, and nobility, and publicly expressed sympathy for the Greek Church and the Hussites, declared that popes and councils could err, and submitted himself to the authority of Holy Scripture above all. "Afterwards, Luther's case seemed to his critics all the more urgent, and they moved quickly to secure his excommunication as a heretic. Once reports of the debate spread, theologians and theological faculties again took sides (as they had after the controversy over the Ninety-Five Theses), university students shifted loyalties and even institutions, and legal proceedings against Luther resumed in Rome. In the wake of Leipzig, Luther began to write highly controversial treatises, denounced the pope as Antichrist, famously burned the bull proscribing his teachings, and was finally excommunicated in January 1521."(Leppin and Maddox, Luther at Leipzig: Martin Luther, the Leipzig Debate, and the Sixteenth-Century Reformations pp. 1 and 11) The Account: The debate was a public affair that went on for seventeen full days (from June 27th to July 15th, 1519), focused upon thirteen academic theses agreed to by Eck and Karlstadt beforehand, with Luther's knowledge and cooperation. Prior to the debate, against the preference of Eck, Luther and Karlstadt insisted that what was said by all three disputants be dictated directly to appointed notaries present during the debate. This had the effect of slowing the debate down considerably and allowed other attendees time to make their own transcripts. It is quite possible that the account printed in this volume was written and edited for the press by Luther's friend Johann Lang of Erfurt (1487-1548), who was present at the Debate. In the brief preface, the editor suggests that he and the eye-witness are one and the same: "Reader. you have here the famous debate held at Leipzig. which we saw and heard ("Habes hic, lector quisquis es, disputationem illam celebrem quam Lipsiae vidimus et audivimus inter insignes viros.") Otto Seitz ("Der authentische Text der Leipziger Disputation"(1903), p. 8 f.), while not disputing the editor's claim that his text is an eye-witness account, demonstrates that the editor was not publishing a copy of the official, notarial report. This is borne out by the editor himself, who writes in his preface that although printing the notarial transcript was officially banned, he is not in violation of the ban on printing because it only applies to the notarial copies, not to private transcripts, of which -he tells us- there were "more than 30" -proof that the authorities did not wish to conceal what was said. Seitz does point out that there are two passages in the printed text that indicate that the editor had access to the official transcript. The Aftermath of the Leipzig Debate: "After Leipzig, the constellation of issues involved in the Luther affair had shifted from questions surrounding grace and repentance to the longstanding problem of authority in the church, especially that of the pope. Luther and Eck had debated how papal authority should be understood. Does the pope rule over all the churches as the vicar of Christ on earth? Does papal spiritual and jurisdictional authority over the whole church reflect the design and intent of Christ the Savior? More to the point, does the pope rule as a monarch in the church 'de iure divino', that is, as a matter of divine law? If so, where does that leave the authority of Holy Scripture? "Questions such as these suggested a vexing series of further queries. What is the relationship between the Bible and church tradition, especially church councils and the writings of the church fathers? Whether the pope is an ecclesial monarch or not, is he subject to Scripture as the Word of God, limited, that is, in what he can say by what the Bible says? In the heated clash at Leipzig in 1519, Eck defended the position that the pope rules over all the particular churches within the one church, and that he does so 'de iure divino'. Luther, on the other hand, publicly argued for the first time that both popes and councils could err, as he thought even a brief perusal of church history would demonstrate. For support of this point he turned at Leipzig not only to Scripture, but to the history of the church and its canon law as well. "Leipzig thus marked a decisive moment in the evolution of what would become known as Protestantism, in contradistinction to 'Roman' Catholicism. Leipzig increased the velocity at which the two sides moved toward these 'termini ad quos' and thus toward ecclesiastical divisi

The Works of Ben Jonson, Which were formerly Printed in Two Volumes, are now Reprinted in One. To which is added A Comedy, Called the New Inn. With Additions never before Published. Neque, me ut miretur turba laboro: Contentus paucis lectoribus

Jonson, Benjamin (ca. 1572-1637) Bound in contemporary speckled calf, very nicely re-backed, boards lightly pitted, board edges and corners bumped (with some small losses to the leather), boards ruled with a double gold filet. The spine is richly tooled in gold, with two citron labels. The contents are in fine condition with scattered light spotting and some rust marks due to impurities in the paper and minor defects as follows: Two repaired tears to blank upper margin of portrait leaf (not touching the image), leaf F4 with marginal defect, O4 with small hole in blank margin, Cc2 with a natural paper flaw affecting a few words, bifolium Zz2-3 browned as usual, Bb4-Cc2 lightly toned, leaf Nnn2 more heavily spotted, small rust hole in leaf Sss3 affecting one letter, tiny hole in Oooo3, small burn-hole in leaf Qqqq3. "This is the first edition in one volume and the last of the folio editions. The 'New Inne' is included in this collection for the first time. Dr. Greg calls attention to the fact that sheet Ccc of this edition is invariably discolored. Besides that leaf, in all copies examined, sheet Zz2-3 is likewise foxed."-Pforzheimer This volume contains all of Jonson's masques, epigrams, plays, verse letters and panegyrics; sonnets, the English Grammar, Timber, or Discoveries; and the translation of Horace's de Arte Poetica. "Jonson's life was tough and turbulent. After his father's early death, Ben was adopted in infancy by a bricklayer and educated by the great classical scholar and antiquarian William Camden, before necessity drove him to enter the army. In Flanders, where the Dutch with English help were warring against the Spaniards, he fought single-handed with one of the enemy before the massed armies, and killed his man. Returning to England about 1595, he began to work as an actor and playwright but was drawn from one storm center to another. He killed a fellow actor in a duel, and escaped the gallows only by pleading 'benefit of the clergy' (i.e., by proving he could read and write, which entitled him to plead before a more lenient court). He was jailed for insulting the Scottish nation at a time when King James was newly arrived from Scotland. He took furious part in an intricate set of literary wars with his fellow playwrights. Having converted to Catholicism, he was the object of deep suspicion after the Gunpowder Plot of Guy Fawkes (1605), when the phobia against his religion reached its height. Yet he rode out all these troubles, growing mellower as he grew older, and in his latter years became the unofficial literary dictator of London, the king's pensioned poet, a favorite around the court, and the good friend of men like Shakespeare, Donne, Francis Beaumont, John Selden, Francis Bacon, dukes, diplomats, and distinguished folk generally. In addition, he engaged the affection of younger men (poets like Robert Herrick, Thomas Carew, and Sir John Suckling, speculative thinkers like Lord Falkland and Sir Kenelm Digby), who delighted to christen themselves 'sons of Ben.' Sons of Ben provided the nucleus of the entire 'Cavalier school' of English poets" (Norton Anthology of English Literature). "One of the most celebrated English poets and dramatists, was born at Westminster in 1574. [.] In 1598 he produced 'Every Man in His Humour', a drama, which at once brought him into notice. One of the characters of this play is said to have been performed by Shakespeare. It was followed by numerous productions, which added to the fame he had already acquired. [.] [Around 1607] he was created poet-laureate by James I. [.] Jonson's convivial habits (perhaps his greatest weakness) caused him to suffer from poverty in his declining years. He was accustomed to meet Shakespeare and other distinguished persons at the drinking houses of London. [.] As a poet he exhibits uncommon classical learning, great intellectual power and acuteness of perception. He unquestionably deserves much praise for refining English poetry and the morals of the English stage. 'I think him,' says Dryden, 'the most learned and judicious writer which any theatre ever had.If I would compare him with Shakespeare, I must acknowledge him the most correct poet, but Shakespeare the greater wit. Shakespeare was the Homer or the father of dramatic poets. Jonson was the Vergil, the pattern of elaborate writing. I admire him, but I love Shakespeare.'" (Thomas' Pronouncer) "Jonson's literary position among his fellow-dramatists is quite unique. In passion, in buoyant humor, in spontaneous felicity of touch, he was inferior to most of them; but he had constructive imagination in an extraordinary degree, a force of intellect and memory which supplied it at every point with profuse material, and a personality which stamped with distinction every line he wrote. He lacked charm, and he failed altogether in drawing fresh and native forms of character; but no one equaled him in presenting the class-types of a highly organized or decadent society, with all their elaborate vesture of custom, manner, and phrase. While most of his fellow-dramatists, moreover, worked on the basis of existing stories, Jonson's plots, though full of traces of his curious reading, are as wholes essentially his own. As a masque-writer he gave lasting worth by sheer poetic force to an unreal and artificial genre. As a literary critic he had no rival."(DNB). FIRST COMPLETE COLLECTED EDITION. With the engraved frontispiece portrait of Jonson as Poet Laureate, by William Elder after Robert Vaughn, bound opposite the title.

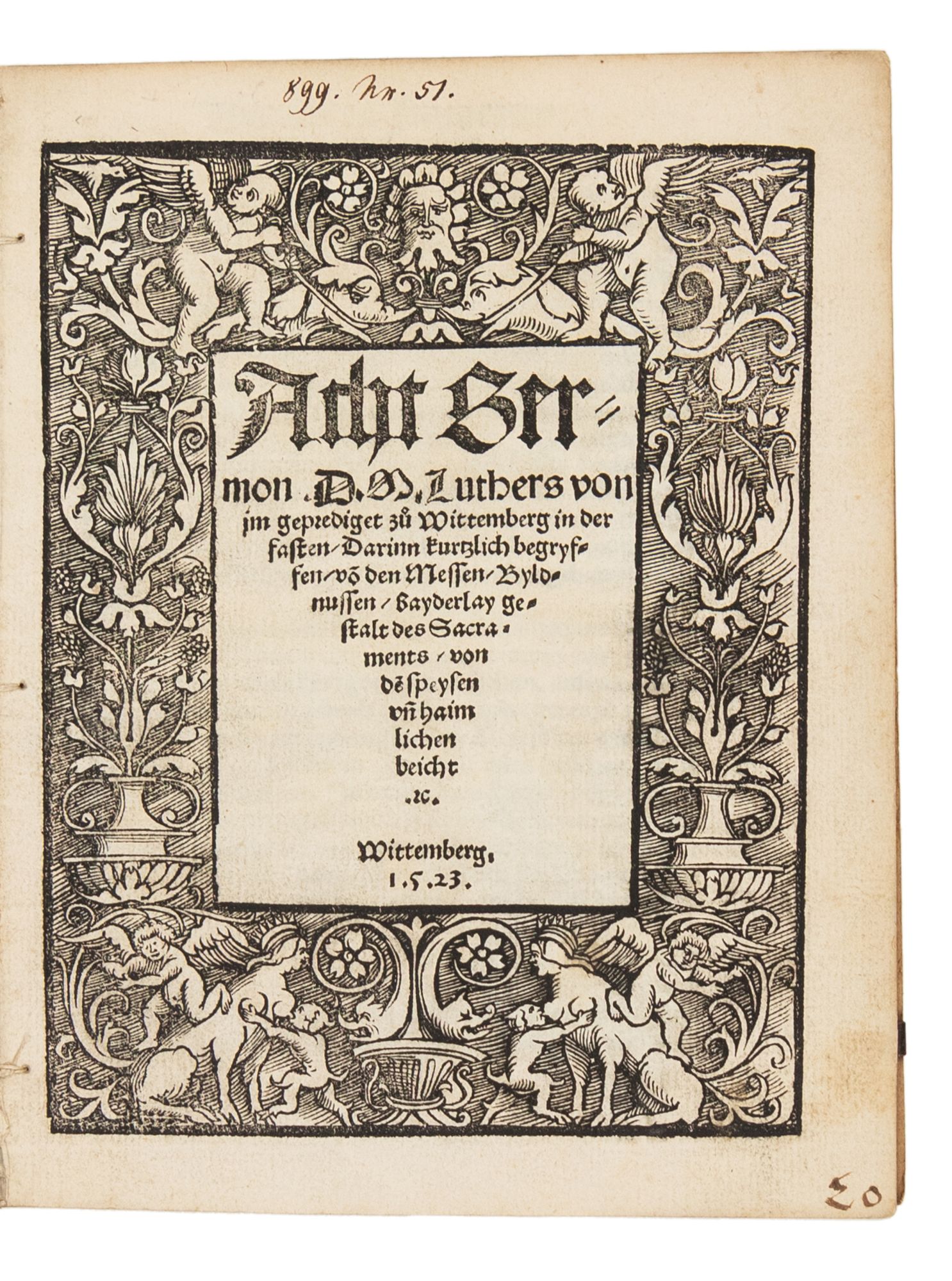

Acht Sermon von D.M. Luthers von jm geprediget zu Wittemberg in der fasten, Darinn kurtzlich begryffen, vo(n) den Messen, Byldnussen, bayderlay gestalt des Sacraments, von de(n) speysen un(d) haimlichen beicht etc.

Luther, Martin (1483-1546) A very nice copy, stab-stiched in drab 20th c. wrappers. With an attractive woodcut title border (Pflugk-Hartung 23). Light maginal fingersoiling to title, blank verso of final leaf lightly soiled. . Two early marginal notes in ink in the blank margin of the title. With a duplicate stamp from the Stadtbibliothek Nürnberg on the rear inner cover. The "Eight Sermons by Dr. M. Luther, preached by him at Wittenberg in Lent, dealing briefly with the masses, images, both kinds in the sacrament, eating [of meats], and private confession, etc." document Luther's efforts to counteract the chaos in Wittenberg that had been caused by Karlstadt, who had instituted radical reforms while Luther was in hiding at the Wartburg. "In December, 1521, Luther returned secretly to Wittenberg from the Wartburg for a three day conference on how to meet the turbulence and confusion caused by the radical reformers. Soon after his return to the Wartburg, Karlstadt put himself at the head of those who favored immediate abolition of Roman practices. At Christmas Karlstadt administered communion in two kinds for the first time in the parish church. (This had been done as early as September in the Augustinian monastery where Gabriel Zwilling conducted mass in the vernacular and abolished private masses.) Karlstadt also declared that confession before communion was unnecessary, that images were not allowable in the church, and that rules of fasting were not binding, and this led to outbreaks of actual destruction of images and altars. He also taught the doctrine of direct illumination by the Spirit, which made scholarship and learning unnecessary for the understanding of the Scriptures. The consequence was that the city schools were closed and the university threatened with collapse. Allied with Karlstadt's followers were the Zwickau prophets, Storch, Drechsel, and Stübner, adherents of Thomas Münzer. "Luther, who hitherto had relied upon Melanchthon's leadership to keep order, returned to Wittenberg on March 6. On March 8 he conferred with Melanchthon, Justus Jonas, Nicholas Amsdorf, and Hieronymus Schurf. On March 9, Invocavit Sunday, he mounted the pulpit in the parish church and preached each day from the ninth to the sixteenth. This remarkable series of sermons, which are powerful, inspired preaching of the gospel, had the effect of restoring tranquility and order almost at once. His task was to lead his congregation away from fanatical enthusiasm back to the spirit of the gospel and to answer the questions that were agitating his people in the light of the gospel. (Further details may be found in an excellent introduction to the sermons in PE 2, 387-390 and in the biographies of Luther and the church histories.). The sermons were transcribed by an unknown amanuensis."(Doberstein, Luther Works Vol. 51). One of 3 printings by Steiner in the year of the first edition.- $5,500

- $5,500

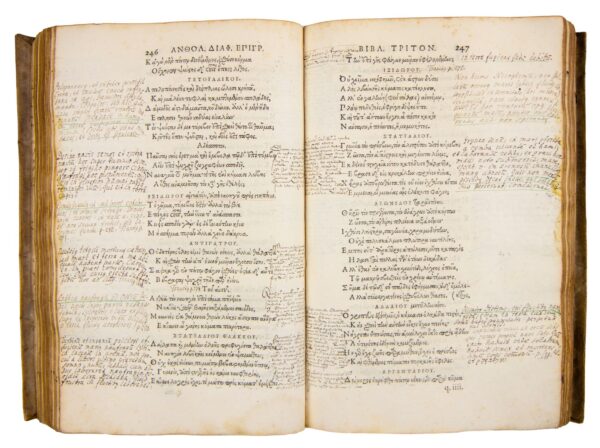

á¼Î½Î ολοΠΠα ΠΠαÏοÏῠν á¼ÏÎ Î ÏαμμΠÏÏν ÏαλαΠῠν, Îµá¼°Ï á¼ÏÏá½° ΠΠΠλΠα Î Î á¿ÏΠμÎνΠ. Florilegium diversorum epigrammatum veterum.

GREEK ANTHOLOGY. Planudes, Manuel (later Maximus) (1255-1305), et al. Bound in seventeenth-century limp vellum. A fine copy, profusely annotated, with scattered instances of damp-staining in the lower margin, and a small piece of the blank margin of leaf y2 snipped away; leaves z7 & 8 with a small marginal paper flaws. Printed in Claude Garamond's Greek type ('grecs du roi'). The extensive translations and annotations are in two different hands, one sixteenth- and the other eighteenth-century. The earlier ones were made by a certain "P (?) Robertus"; the later ones by the poet Johannes Nicolaus Goetzius (1721-1781). On the pastedown is the name of a third owner, Th. Fritzsche (dated 1872), who later added quotations from a study on the Greek Anthology by Georg Finster, published 1876. THE TRANSLATIONS AND ANNOTATIONS: 1. The first annotator identifies himself on the title-page: "Verus huius libri possessor P(?) Robertus" and "Emptus genevae 16 calendas Augusti: Anno a Christo nato. 1584" ("The true owner of this books is JN Robertus. The book was bought in Geneva on 17 July 1584.") Robertus translated nearly 300 epigrams, writing these translations on the inner margins; in the outer margins he transcribed translations by other humanists (or made references to them.) Among these humanists are Henricus Stephanus (apparently hisEpigrammata selecta, 1570), Bellicarius, i. e. François Beaucaire de Peguillon, who published his Latin translation of the first book of the Anthology in 1543 (see Hutton 93 ff.), Andrea Alciatus (Emblemata), Ottomar Luscinius (Nachtigall; inSelecta Epigrammta, Basel 1529), JanusCornarius (also in the 1529 Basel edition), Thomas More, Paul Melissus Schedius, Janus Pannonius (Epigrammata, Basel 1518), Ursinus Velius (Poemata, Basel 1522), Johannes Gorraeus, Arnoldus Vesaliensis, and perhaps a few more. The references end on page 151, his translations continue to page 303. The second owner, Johann Nikolaus Götz (1721-1781), is identified by his inscription on the title-page, "Joh. Nic. Goetzii, ex dono d: Wund Consiliarii ecclesiastici Palatini 1772." This may be the churchman I. W. F. Wund, director of the Gymnasium at Heidelberg. (See Johann Heinrich Andreae:Spicilegium post contatum historico-litterarium De Gymnasio Heidelbergensis., Heidelberg 1765 p. 14, footnote). Goetz (1721-1781) was a pastor and poet. It is said that he can hardly be overestimated as a gifted translator of Greek works into German; his German translation of Anacreon, first published in 1746, was of great influence on contemporary poetry, initiating the anacreontic movement in German poetry; his work was highly esteemed by Herder, Wieland, Voß, Lessing, Goethe and others. In our copy, Goetz translated more than 700 epigrams from Greek into Latin; they are written on the outer margins of the pages. In addition to translating the poems, he makes references to Helvetius (De l'esprit), Grotius, Heinsius, Francius, Ausonius, Buchanan, Johannes Secundus, Young (Nachtgedanken /Night Thoughts), Charpentier, Diogenes Laertius, Opitz, Polizian, Catull, and others. Many annotations by Goetz refer to the Poemata, Amsterdam 1682, of the Dutch poet Petrus Francius/Pieter de Fransz. Fabricius (Bibliotheca Graeca,1795, vol. iv, p. 448) writes about this Dutch poet: âAb eo temporare qui operae pretium in hoc genere fecerit memorare juvat unum Petrum Francium, Amstelodamensium nuper Musarum decus, in cujus Poematis bene multa exstant Epigrammata translata de Graeco suavissime et felicissime. Viderunt lucem Amst. 1682.12. & 1697.8." See also Hutton,The Greek Anthology. pp. 271f. Many other annotations refer (by page number) to translations of various poems from the Anthology made by Daniel Heinsius and published in his Poemata Graeca & e graecis latine reddita (Leiden 1640.) Here are two examples of the translations by Goetz: 1. (In Therimachum, Greek text, p. 283): Îá½ÏÏμαÏοΠΠεΠλῠÏοÏá½ Ïαá½Î»Î ον αἱ Î ÏÎµÏ á¼¦Î»Î Î¿Î½ á¼Î¾ á½ÏÎµÎ¿Ï ÏολλῠνΠÏÏμεναΠÏÎ ÏνΠ, αἰαá¿, ÎÎ ÏΠμαÏÎ¿Ï Î á½ ÏαÏá½° Î ÏÏ á¿ Ïὠν μΠκÏον εá½Î εΠá½Ïνον, á¼ÎºÎ¿Î μήΠΠΠ᾿á¼ÎºÏÏ Ïá½ ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ±Î½Î Î¿Ï . (Goetz' translation, in the outer margin opposite the printed Greek): Spontaneae timidae ad stabulum vaccae venerunt ex monte, multa adspersa nive. Hei, hei, Therimachus v. prope quercum longe dormit somnum: jacet v. ex igne coeli. (âv." stands for: vacat. Goetz uses it when he omits a particle like Î Î in his translation.) For comparison, here is Heinsius' version, to which Goetz refers at the top of the page ("Dan. Heins.Poemata, p. 129-131"): Ad stabulum moestae veniunt e monte juvencae Sponte sua, multis irriguae nivibus. At te Therimache, hanc ad quercum longa tenet nox, Sopitum teli viribus aetherei. 2. (Hegesippi in Timonem Misanthropum, p. 218): á½Î¾Îµá¿Î±Î ÏΠνÏÎ ÏεÏá½ Ïὠν ÏÎ Ïον εἰÏὠν á¼ÎºÎ±Î½Î αΠÎαὠÏκÏλοÏεÏ⧠ΠλΠÏÎµÎ Ï ÏÎ¿á½ºÏ ÏÏΠαÏ, ἢν ÏÏοÏÎ Î Ï⧠ΤΠμÏν μΠÏΠνΠÏÏÏÎ¿Ï á¼Î½Î¿Î κÎÏ. á¼Î»Î»á½° ÏÎ ÏελΠε οἰμÏΠεΠν εἠÏÎ±Ï ÏολλΠ. ÏÎ ÏελΠε μÏνον. (Goetz' translation, again in the outer margin opposite the printed Greek): Acuta ubique circa tumulum sunt vepres et pali : nocebis pedibus si accedas. Timon Misanthropus inhabito, sed praeteri multa ma- ledicens. Praeteri solum. For comparison, here is Petrus Francius' version, from his "Poemata"(1682), to which Goetz refers at the foot of his own translation ("Francius p. 264"): Vepribus ac palis bustum hoc vallatur acutis. Effugite hinc: plantas ne fera laedat humus. Hanc habito Timon, generis vestri hostis: abite, et mihi, quae vultis, dicite; abite modo. On page 522 Goetz has added, together with his Latin translation, a Greek epigram of Meleager not present in Estienne's edition: Îá½"ÏÎ Î¿Ï á¼Î¼ÏνεÏÏÎ±Ï Î½Î±ÏÏÎ±Î Ï Î½ÏÏοÏ, á½ Î Ï ÏÎÏÏÏεÏ, Secundus spirans nautis notus, o infelices in amore, á¼Î¼Î ÏÏ Î¼ÎµÎ½ ÏÏ Ïá¾ Ï á¼ ÏÏαÏεν á- $12,000

- $12,000

The Works of our ancient, learned, [and] excellent English poet, Jeffrey Chaucer: as they have lately been compar’d with the best manuscripts; and several things added, never before in print. To which is adjoyn’d, The story of the siege of Thebes, by John Lidgate, monk of Bury. Together with the life of Chaucer, shewing his countrey, parentage, education, marriage, children, revenues, service, reward, friends, books, death. Also a table, wherein the old and obscure words in Chaucer are explained, and such words (which are many) that either are, by nature or derivation, Arabick, Greek, Latine, Italian, French, Dutch, or Saxon, mark’d with particular notes for the better understanding their original

Chaucer, Geoffrey (d. 1400) Bound in 17th c. sprinkled calf, the boards framed by a repeating gold tool. Discreetly rebacked preserving most of the original spine, corners bumped; new endpapers. With the full-page engraved portrait of Chaucer bound opposite the title page and a second title page (leaf c1) with a three-quarter page woodcut of Chaucer's arms. A very fine, crisp copy with trivial faults: a burn-hole in blank margin of leaf E4; two small spots on leaf N3; lvs. T2-3 lightly toned, clear dampstain to gathering Uu; occasional rust spots. The contents are: "The Canterbury Tales", together with the "Prologues"; "The Romaunt of the Rose"; "Troilus and Criseyde"; "The Legend of Good Women"; Chaucer's translation of Boethius' "Consolation of Philosophy"; "The Dreame of Chaucer"; "The Assemblie of Foules"; The Flower of Courtesie"; "How Pitie is Dead"; "La Belle Dame sans Mercie"; "Annelida and false Arcite"; "The Assembly of Ladies"; The Conclusion of the Astrolaby"; "The Complaint of the Black Knight"; "A Prayse of Women"; The House of Fame"; "The Testament of Love"; "Jake Upland"; John Lydgate's "Siege of Thebes" and a number of other minor works. Thomas Speght: "The schoolmaster and literary editor Thomas Speghtbecame interested inChaucerat Cambridge, an enthusiasm he shared withFrancis Beaumont, who later contributed a prefatory letter toSpeght'sChauceredition. It is possible that they formed part of a circle of Chaucerians at Peterhouse and it is perhaps significant that they overlapped with the Cambridge years of another noted Chaucerian,Edmund Spenser(1569-76). After Cambridge,Speghtappears to have maintained a private interest inChaucer. In October 1592 a reprint ofChaucer'sworks was entered in theStationers'register and by the time this work appeared under the titleThe Workes of our Antient and Lerned English Poet, Geffrey Chaucer, Newly Printedearly in 1598,Speghtwas the editor. "In preparing the editionSpeghtcertainly had the help of the antiquaryJohn Stowand the 1598 edition ofChauceris in some ways not much more than a revision ofStow'sown edition of 1561. AlthoughSpeghtlists works ofChaucer'swhich he claims were 'never before imprinted' (Speght,Workes, sig. Aiiiv) most of them in fact appeared inStow'sedition, suggesting the extent to which he saw his task as simply presenting anew whatStowhad done. "Nevertheless,Speght'snotes and introductory material are far more elaborate than in any previous edition and he was the first to provide a substantial glossary. While this suggests thatChaucer'slanguage was becoming difficult to read, it is also part of the process whereby the Chaucerian text was dignified by the kind of extensive apparatus a classical author might receive. Speghtalso contributed new annotations to the text ofChaucer, of which the most famous is his comment on a reference to the legendary hero Wade.Speghtwrote, 'because the matter is long and fabulous, I passe it over' (Speght,Workes, sig. Bbbb.iiiiv), an unfortunate omission as all knowledge of stories of Wade has subsequently been lost. "Also among the introductory material was an extensive biography, which informed all subsequent accounts of the poet's life until the 1840s. Several common beliefs aboutChaucerwere established here, some of them on the basis of texts attributed to the poet, but spurious. Hence,Chaucerwas thought (as supposed author ofThomas Usk'sThe Testament of Love) to have spent time in exile in the 1380s and was claimed as a fellow Cantabrian on the basis ofThe Court of Love.Speghtplayed upChaucer'slinks withJohn of Gauntand enhanced the image of the poet as a man who 'alwaies held in with the Princes, in whose daies he lived' (Speght,Workes, sig. Bviv). He was also the source of the biographical detail thatChaucerwas once fined2s.for beating a Franciscan friar in Fleet Street. The document supposedly recording this was found in the Inner Temple, leadingSpeghtto suggest that the poet studied law there. While the beating of the friar has never been disproved, it is suspiciously convenient evidence of an early and vigorous tendency to anti-clericalism on the poet's part, which, making him appear at odds with theChurch of Rome, helped to refashion aChauceracceptable to Reformation England. "Criticisms of the 1598 edition were forthcoming fromFrancis Thynne, son of the earlierChaucereditorWilliam Thynne, in hisAnimadversions uppon the Annotacions and Corrections . of Chaucers Workes.Speghttook heed of the criticisms, though they were not always accurate, and in a new edition ofChaucerappearing in 1602 he departed more decisively fromStow. In this work the ChaucerianÅ"uvrewas augmented by theABC, in print for the first time, and the anti-clerical (but non-Chaucerian)Jack Upland, which further bolstered the poet's reputation as a Wycliffite. "In 1687 a reprint of this work with a few alterations appeared, and remained in use even after the publication ofJohn Urry'smuch reviledChauceredition of 1721.Thomas Tyrwhitt, editing theCanterbury Talesin the 1770s, used the 1602 and 1687 editions ofSpeght, taking the latter as his base text. With a period of influence stretching from the late sixteenth century to the late eighteenth, then,Speght'sChaucerhas been the most durable of anyChauceredition.(Matthews, Oxford DNB).- $9,800

- $9,800

The anatomy of melancholy. What it is, with all the kinds causes, symptomes, prognostickes, & seuerall cures of it. In three partitions, with their severall sections, members & subsections. Philosophically, medicinally, historically, opened & cut up. By. Democritus Iunior. With a satyricall preface, conducing to the following discourse. The fourth edition, corrected and augmented by the author

Burton, Robert (1577-1640) Bound in attractive contemporary English calf (rebacked, with the majority of the original spine preserved), both boards richly and ornately tooled in gold with large central arabesques, roll-tooled compartments, and floral tools. Surface of the boards lightly rubbed, corners bumped, a few scrapes to the lower board. Modern endpapers. A very good, crisp copy, complete with the engraved title page depicting various types of melancholy and the explanatory "Argument of the Frontispiece". A small piece of the upper blank corner of the first leaf has been excised (not affecting the text.); outer edge of first leaf and engraved title chipped; edges of first few leaves lightly browned, blank corner of engraved t.p. with 17th c. ownership scored through and illegible; small rust holes in lvs. M3, Rr1 and Yy4; small loss to blank lower margin of leaf Cc2 (far from the text), tiny natural flaw in leaf Hh2, affecting 2 letters without loss of sense; verso of last leaf lightly soiled, blank recto of first leaf soiled. Light stain to first text leaf. "This great book was destined to become the most frequently reprinted psychiatric text. It may properly be called the first psychiatric encyclopedia for nearly one thousand authors are cited, about half of them medical. It was so popular that five editions appeared in Burton's lifetime and three more in the seventeenth century."(Hunter and Macalpine) "The one major product of [Robert Burton's] eccentric life was his 'Anatomy of Melancholy' (1621), a long and serious study of the causes, symptoms, and cures of the 'black distemper' from which, reportedly, the author himself suffered. The erudite Oxford scholar who never married or even traveled 'but in map or card' put all of his life in 'The Anatomy of Melancholy', a work so profusely documented with thousands of allusions to authors from Galen to Bacon as to suggest that for Burton the choicest part of living was reading. His treatise is systematically divided into three principal parts: causes, symptoms, and prognoses of melancholy; cures and alleviations of melancholy; and symptoms of love and religious melancholy, the two classic manifestations of the malady. Burton's' tripartite arrangement, however, does not prevent him from engaging in long digressions on human anatomy and the nature of spirits, observations on manners and morals, or descriptions of his own ideal commonwealth. For most readers, Burton's didactic or satiric anecdotes and well-placed allusions, however digressive, constitute one of the chief allurements of his book. Few readers have regretted the fact that although Burton was thoroughly conversant with Bacon and the 'new science,' and sympathetic to his aims, he could not resist imposing on every problem his own eccentric and restless imagination. Nor could he, for all his scientific values, overcome his peculiar conceptions of logic and his penchant for proving a case by the medieval method of totaling masses of authorities on either side of a given question." (James Ruoff in Crowell's Handbook of Elizabethan and Stuart Literature, pages 50-51) Samuel Johnson used the "Anatomy of Melancholy" in compiling his Dictionary. Boswell reports that Burton's was the only work that Johnson rose early in the morning to read with pleasure.- $12,500

- $12,500

Catullus et in eum Commentarius M. Antonii Mureti. ab eodem correcti, & scholiis illustrati, Tibullus, et Propertius

Catullus, Gaius Valerius (ca. 84-ca.54 B.C.); Tibullus (ca. 50-ca.18 B.C.); Propertius, Sextus. (ca. 49-ca. 16 B.C.); Sappho (d. ca. 570 B.C.) With three divisional title pages, all featuring the Aldine dolphin and anchor device. Bound in contemporary blind-tooled pigskin (lightly soiled, corners bumped, small hole in pigskin at head of spine, wear at extremities), signed "A.S.K." and dated 1562 on the upper board. Title page lightly soiled, intermittent mild foxing, light marginal staining in places. A few manuscript notes and underscores. The binding: decorated with blind-stamped images of Apollo (with harp)and the Muses: Caliope (with zither), Thalia (with lute), Euterpe (with horn), Terpsichore (with viola). The Euterpe stamp is signed "S.N.", that of Terpsichore is dated "1549". The binding is probably the work of the Wittenberg binder Conrad Neidel (active 1542-15602), see Haebler, Vol. I, p. 308. This edition marks the second appearance of the celebrated commentary of Marc Antoine Muret, "the most important commentary on Catullus since that of Parthenius in 1485."(Gaiser). Muret, who had fled France to avoid trial for homosexuality, prepared his commentary while taking refuge in Italy with Paul Manutius. Muret was the first commentator to pair Sappho's Greek poem "Phainetai moi kênos îsos theoisin"(Sappho 31) with Catullus' poem 51, "Ille mi par esse deo videtur", which Catullus based on Sappho's poem. "In 1552 Muret lectured on Catullus and other Latin poets in Paris, perhaps at the College du Cardinal Lemoine or the College de Boncourt. Included in his large and enthusiastic audiences were several poets of the Pléiade -most notably Ronsard, his friend and near contemporary. Muret's lectures created a fashion for Catullan poetry. His own neo-Latin collection, Juvenilia (1552), contains several Catullan imitations, but Catullus is still more important in the poetry of the Pléiade, much of which appeared close on the heels of his lectures."(Gaiser) Late in 1553 Muret was forced to leave Paris, where he was persecuted for being a homosexual. Earlier in the year he had been accused of "unnatural vice" and imprisoned at the fortress of Châtelet "and would have died of starvation had his friends not intervened to secure his release. Disgraced at Paris and reduced to poverty, he fled to Toulouse, where he eked out a living by giving lessons in law. He was accused a second time of having committed sodomy, in this instance with a young man named L. Memmius Frémiot, and on the advice of a councilor he absconded once more. He was sentenced to death in absentia and burned in effigy with Frémiot in the Place Saint-Georges as a Huguenot and sodomite. He crossed the Alps in disguise and was warmly received for a time in Venice, while in France his memory was ceaselessly vilified." (Warren Johansson) Soon after arriving in Venice, in May 1554, Muret was befriended by Paul Manutius, who, learning of his enthusiasm for Catullus, persuaded him to produce a commentary. Muret went to work and completed the task in a little less than three months, as he says in the dedication, dated October 15, 1554. "Since Muret had been in Venice only a few months, his commentary on Catullus was no doubt largely drawn from the Paris lectures. His notes display a combination of learning and poetic sophistication that would have appealed to the Pléiade. More than any of his predecessors except Valerianus, he discusses the artistic qualities of Catullus' work and the details of vocabulary and meter that work together to secure an effect. He appends a poem of his own in galliambics to his discussion of the meter in Cat. 63, discusses the appropriateness of the similes in Cat. 68 (which he regards as perhaps the most beautiful elegy in Latin) and discourses on the delight of studying Catullus' 'translations' in close conjunctions with their Greek models. He is the first commentator to print Sappho's poem with Cat. 51 (see folio 57), and he laments the loss of Callimachus' 'lock of Berenice' in the discussion of Cat. 66 and prints all the fragments of that poem known to him. "Muret is interested in the text, but he is cautious about emendations and adamant in refusing to admit modern conjectures and supplements, no matter how apposite. Muret's commentary was the first to be published since that of Guarinus in 1521 and the most important since that of Parthenius in 1485." (Gaisser, "Catullus", CTC Vol. VII, pp. 260-261) "Previous writers, Parthenius, Palladius, Avancius, Guarinus, had concerned themselves only with the elucidation of textual and grammatical difficulties. Muret pays far more attention to the literary and aesthetic side of Catullus' poems than any other commentator of the period. It is clear that he is professionally interested, as a poet himself and the teacher of poets, in Catullus' mastery of his art. He makes quite a number of literary and aesthetic judgements and these, sporadic and unsystematic though they are, form precious evidence of the sixteenth century attitude to Catullus. "On Catullus LI, the translation of Sappho's ode, Muret remarks: 'What man is there, at least amongst those who have some feeling for literature and culture, who does not derive the keenest pleasure in comparing the lines of that woman who far surpasses all men in this genre, and those of the most voluptuous of all the Latin poets?' ("poetae Latinorum omnium mollissimi.") Similarly on Catullus' Coma Berenices (LXVI) he bewails the loss of Callimachus' elegy on the same theme, which deprives posterity of the pleasure of comparing the great Greek poet with Catullus 'Latinorum poetarum sine controversia politissmus'." (Fitzgerald, Catullus and the Reader, the Erotics of Poetry). SECOND EDITION WITH MURET'S COMMENTARY (1st 1554).- $5,500

- $5,500

De revolutionibus orbium coelestium libri VI : habes in hoc opere iam recens nato, & ædito, studiose lector, motus stellarum, tam fixarum, quàm erraticarum, cum ex ueteribus, tum etiam ex recentibus obseruationibus restitutos : & nouis insuper ac admirabilibus hypothesibus ornatos : habes etiam tabulas expeditissimas, ex quibus eosdem ad quoduis tempus quàm facilli me calculare poteris : igitur eme, lege, fruere

Copernicus, Nicolaus (1473-1543) Bound in attractive, contemporary Parisian calf with some discreet repairs. The boards are blind-ruled and adorned with gold-tooled ornaments. This is one of very few to have appeared on the market in a contemporary binding. The text is in excellent condition, with just minor blemishes (small early erasure of an ownership inscription on the title just slightly touching the "D." in the date. Light damp-staining to first six leaves.) Collation as in Horblit; this copy without the errata leaf -printed separately and later- that is found in a minority of copies (about 20 percent). Preserved in a morocco-backed box. Provenance: At the foot of the title-page, an early signature has been thoroughly lined through. 17th- or 18th-century inscription on title of the Jesuit College of Paris. Bookplate of Gustavus Wynne Cook (1867-1940, amateur astronomer, collector, and benefactor of the Franklin Institute). Franklin Institute bookplate. Soldat Sotheby Parke-Bernet, New York, November 1977, lot 85. Purchased by Pierre Berès at Sotheby's London, 21 October 1980 and sold to a prominent Spanish private collector. "The earliest of the three books of science that most clarified the relationship of man and his universe (along with Newton's Principia and Darwin's Origin of Species)."-Dibner, Heralds of Science, 3. This work is the foundation of the heliocentric theory of the planetary system and the most important scientific text of the 16th century. Copernicus began to work on astronomy on his own. Sometime between 1510 and 1514 he wrote an essay that has come to be known as the Commentariolus that introduced his new cosmological idea, the heliocentric system, and he sent copies to various astronomers. He continued making astronomical observations whenever he could, hampered by the poor position for observations in Frombork and his many pressing responsibilities as canon. Nevertheless, he kept working on his manuscript of On the Revolutions. In 1539 a young mathematician named Georg Joachim Rheticus (1514-1574) from the University of Wittenberg came to study with Copernicus. Rheticus brought Copernicus books in mathematics, in part to show Copernicus the quality of printing that was available in the German-speaking cities. He published an introduction to Copernicus's ideas, the Narratio prima (First Report). Most importantly, he convinced Copernicus to publish On the Revolutions. Rheticus oversaw most of the printing of the book, and on 24 May 1543 Copernicus held a copy of the finished work on his deathbed. It is impossible to date when Copernicus first began to espouse the heliocentric theory. Had he done so during his lecture in Rome, such a radical theory would have occasioned comment, but there was none, so it is likely that he adopted this theory after 1500. His first heliocentric writing was his Commentariolus. It was a small manuscript that was circulated but never printed. We do not know when he wrote this, but a professor in Cracow cataloged his books in 1514 and made reference to a "manuscript of six leaves expounding the theory of an author who asserts that the earth moves while the sun stands still" (Rosen, 1971, 343). Thus, Copernicus probably adopted the heliocentric theory sometime between 1508 and 1514. Rosen (1971, 345) suggested that Copernicus's "interest in determining planetary positions in 1512-1514 may reasonably be linked with his decisions to leave his uncle's episcopal palace in 1510 and to build his own outdoor observatory in 1513." In other words, it was the result of a period of intense concentration on cosmology that was facilitated by his leaving his uncle and the attendant focus on church politics and medicine. In the Commentariolus Copernicus listed assumptions that he believed solved the problems of ancient astronomy. He stated that the earth is only the center of gravity and center of the moon's orbit; that all the spheres encircle the sun, which is close to the center of the universe; that the universe is much larger than previously assumed, and the earth's distance to the sun is a small fraction of the size of the universe; that the apparent motion of the heavens and the sun is created by the motion of the earth; and that the apparent retrograde motion of the planets is created by the earth's motion. Although the Copernican model maintained epicycles moving along the deferent, which explained retrograde motion in the Ptolemaic model, Copernicus correctly explained that the retrograde motion of the planets was only apparent not real, and its appearance was due to the fact that the observers were not at rest in the center. The work dealt very briefly with the order of the planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, the only planets that could be observed with the naked eye), the triple motion of the earth (the daily rotation, the annual revolution of its center, and the annual revolution of its inclination) that causes the sun to seem to be in motion, the motions of the equinoxes, the revolution of the moon around the earth, and the revolution of the five planets around the sun. The Commentariolus was only intended as an introduction to Copernicus's ideas, and he wrote "the mathematical demonstrations intended for my larger work should be omitted for brevity's sake.". In a sense it was an announcement of the greater work that Copernicus had begun. The Commentariolus was never published during Copernicus's lifetime, but he sent manuscript copies to various astronomers and philosophers. He received some discouragement because the heliocentric system seemed to disagree with the Bible, but mostly he was encouraged. Although Copernicus's involvement with official attempts to reform the calendar was limited to a no longer extant letter, that endeavor made a new, serious astronomical theory welcome. Fear of the reaction of ecclesiastical authorities was probably the least of the reasons why he delayed publishing his book. The most important reasons for the delay- $2,500,000

- $2,500,000

Dialogi. Fortuna. Febris prima. Febris secunda. Trias Romana. Inspicientes: https://rarebookinsider.com/rare-books/dialogi-fortuna-febris-prima-febris-secunda-trias-romana-inspicientes/