![Theorie de la Perspective [with:] Nouvelle Theorie du Melange des Coulêurs. Tirée de l'Optique de M. Newton . [Paris](https://rarebookinsider.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/30623450518-600x853.jpg)

LACAILLE, Nicolas-Louis, Abbé de (1713-1762)

Folio (370 x 240 mm), ff [10], with one loose folded sheet of tables and one partsheet of astronomical observations (see below), ink on paper, with numerous diagrams and tables, text and tables with extensive revisions and corrections; in very good condition, unbound. A detailed manuscript on perspective and optics, with extensive tables for calculating the distance of objects, probably used in Lacailles courses on mathematics which he taught at the Collège Mazarin in Paris. The work begins with the Théorie de la Perspective. This is followed by Pratique de la Perspective. Five full-page and detailed tables follow, with the vertical columns titled Distances de lObject au Plan du Tableau, and the horizontal columns titled Distances de lObject au plan Horizontal ou au plan Vertical, containing 10,000 calculations. The next section is titled Regles pour trouver La Perspective des Objets dont les faces sont inclinées au Plan du Tableau, accompanied by another extensive table with 1700 calculations. The final perspective section is titled Sur Le Point de vuë, et le Lieu de loeil. The second part is devoted to Newtons theory of colours, and seems to be based upon the French edition of Brook Taylors work on perspective. The French translation appeared in Amsterdam in 1757 and was titled Nouveau Principes de la Perspective Linéaire, which contained Essai sur le Mêlange des Couleurs, par Newton. However, LaCailles text is not a translation of that of Taylors, and in fact a radical reworking of the basic geometric principles of perspective. The tables are unique, the result of a massive effort of computation, one of Lacailles noted skills. Many of these techniques are related to his observational skills in astronomy and in calculating astronomical positions and distances. The small astronomical manuscript relates to observations he made at the Mazarin: Par un milieu entre six observations dun coté deduites au 1 Jan 1748 du egard a la observation eu à la precéssion. LaCaille was an astronomer who was a prodigious observer and calculator, having observed over 10,000 stars in the Southern hemisphere, and named 14 of the 88 constellations. Initally he was assistant to Jacques Cassini and participated in a series of surveying projects, and in 1739 in remeasuring the arc of the meridian. Appointed professor of mathematics at the Collège Mazarin, he built his own observatory where he carried out astronomical observations. In 1752 he made an astronomical expedition to the Cape of Good Hope, where he built an observatory and carried out a prodigious series of observations, including the discovery and cataloguing of 42 nebulae. Lalande stated that he made more observations and calculations than all previous astronomers combined. Upon his return to Paris in 1754 he resumed his post and teaching duties at the Mazarin. His students included the great chemist Antoine Lavoisier

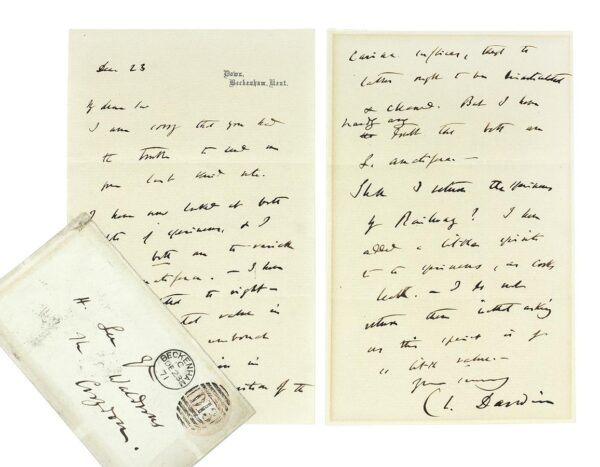

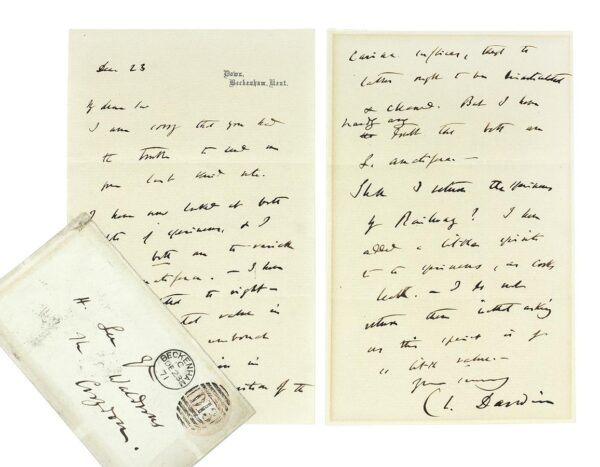

DARWIN, Charles (1809?Äì1882)

DARWIN, Charles (1809?Äì1882). Autograph letter signed to biologist Henry lee, concerning the identification of species of barnacles, dated 23 December 1871. Down, Beckenham, Kent, 23 December, 18718vo (2 pages on a single folded sheet, 200 x 259 mm) on printed letterhead Down, Beckenham, Kent?Äô, in ink, with original envelope addressed in Darwin?Äôs hand, stamped and postmarked; in very good condition, in a quarter-leather folding case. $18,500A fine and fascinating letter (with the original addressed envelope; these rarely survive), written in Darwin?Äôs scientific maturity but reverting to his early expertise in the anatomy of barnacles. Barnalces were the subject of his first major scientific monograph, published in two volumes by the Ray Society in 1851, 1854 (A monograph of the sub-class Cirripedia, with figures of all the species. The Lepadid? ; or, pedunculated cirripedes . ). Darwin undertook the anatomical investigation of barnacles both as a result of specimens he collected during the Beagle voyage and also to demonstrate his mastery of detailed anatomical and taxonomic investigation. His work established the nomenclature and classification criteria that became standard up to this day.The letter concerns specimens of gooseneck barnacles submitted to Darwin by Henry Lee for classification. Darwin replies in detail with his characteristic attention and kindness to any serious scientific correspondent, even while he was engaged in correcting proofs for the sixth edition of the Origin of Species. Darwin conducted microscopic anatomical examinations of Lee?Äôs specimens and writes: ?ÄòI have now looked at both lots of specimens, & I think both are the variable L. ?anatifera.?Äî I have disarticulated the right-hand scutal valve in both & the umbonal teeth are plain in both. This with position of the carina suffices, though the latter ought to be disarticulated and cleaned. But I have hardly any doubt that both are L. ?anatifera . ?Äô.?ÄòDarwin's work on barnacles (Cirripedia), conducted between 1846 and 1854, has long posed problems for historians. Coming between his ?transmutation notebooks ?and the ?Origin of species, it has frequently been interpreted as a digression from Darwin's species work. Yet when this study is viewed in the context of Darwin's earlier interests, in particular his studies of marine invertebrates carried out during his student days in Edinburgh and later on board the ?Beagle, the ?monograph on the Cirripedia ?seems less anomalous. Moreover, Darwin's study of cirripedes, far from being merely a dry, taxonomic exercise, was a highly theoretical work that addressed several problems at the forefront of contemporary natural history. Treating a group of organisms of considerable interest to mid-nineteenth century naturalists and approaching their classification using the most recent methods available, Darwin was able to provide a thorough taxonomic study that has remained a standard work in cirripede morphology and systematics. For Darwin personally, the barnacle work perfected his understanding of scientific nomenclature, comprising both theoretical principles and technical facility with the methods of comparative anatomy. It also provided him with an empirical means of testing his views on the species question (Crisp 1983) ?Ä Darwin's evolutionary interpretation of the meaning of classification explains why he readily adopted embryology as a methodological tool for revealing homologies?Äô (Cambridge University, Darwin On-line).Darwin exchanged several letters with Henry Lee.Henry Lee, naturalist, succeeded John Keast Lord (1818?Äì1872) as naturalist of the Brighton aquarium in 1872, and was for some time a director there. While at the aquarium he instituted important experiments on the migration of smelts, the habits of herring, and the nature of whitebait and crayfish. His Aquarium Notes (1875) for the use of visitors, was able and attractive. Lee was also author of The Octopus (1874), The White Whale (1878), Sea Fables Explained (1883), and Sea Monsters Unmasked (1883). The last two works were part of a series of handbooks issued in connection with the International Fisheries Exhibition in London in 1883. He also published The Vegetable Lamb of Tartary: a Curious Fable of the Cotton Plant (1887).?ÄòLee was also an energetic collector of natural history specimens, and a skilful worker with the microscope. On 5 April 1866 he was made a fellow of the Linnean Society, and he was founder of the Croydon Microscopical and Natural History Club established on 6 April 1870. He was also a member of the Geological and Zoological societies of London?Äô (ODNB).Darwin Correspondence Project n 8118B (partial transcript only)

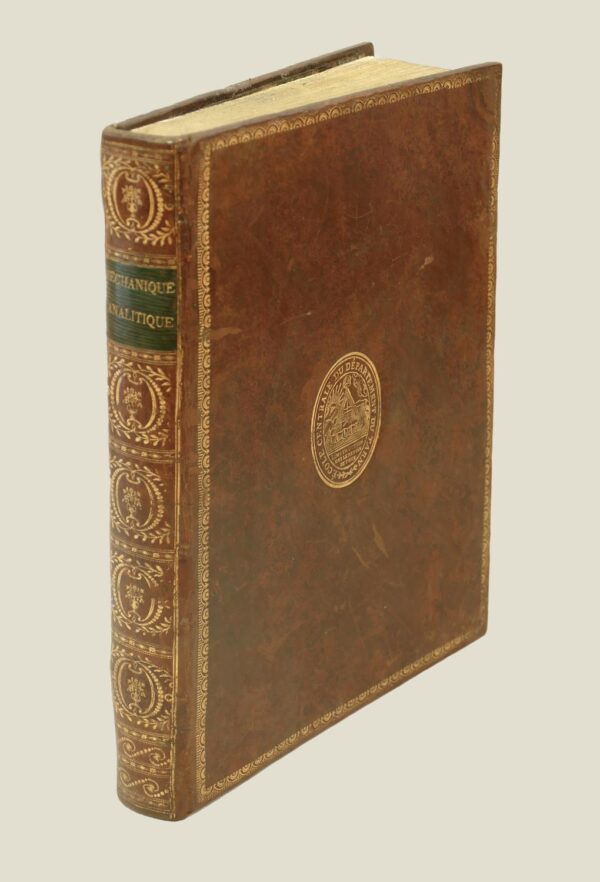

LAGRANGE, Joseph Louis (1736?Äì1813)

LAGRANGE, Joseph Louis (1736?Äì1813). M? chanique analytique. Paris, La Veuve Desaint, 17884to (256 x 195 mm), pp xii, 512; a fine copy in contemporary French calf, gilt neoclassical panels on sides and gilt panels with wreaths and urns on spine.First edition of Lagrange's masterpiece, which has been described as ?Äòperhaps the most beautiful mathematical treatise in existence.?Äô This is the scarcest of Lagrange's major works.?ÄòIt was reserved for Lagrange to mould theoretical mechanics into a system, and by combining the principle of virtual velocities with D'Alembert's Principle, to derive fundamental mechanical equations which describe the motion of any system of bodies. These important results were set forth in Lagrange's masterpiece, the M? chanique Analytique (Paris, 1788), which laid the foundations of modern mechanics, and which occupies a place in the history of the subject second only to Newton's Principia. The two works differ in one essential respect, namely, whereas Newton derives his results purely geometrically, or synthetically, with the aid of figures, Lagrange, dispensing with diagrams, treats the subject in an entirely analytical manner. He followed the example of Euler in his analytical treatment and his efforts to find the most comprehensive formulae which should enable as many particular cases as possible to be treated on the same lines. In this sense Lagrange's work has been described by Mach as one of the greatest contributions to the economy of thought?Äô (Wolf, History of science. in the eighteenth century, pp. 69-70).Provenance: gilt arms of the ?âcole centrale du d? partement du Tarn on upper cover and stamp of ?âcole sup? rieure de commerce et d?Äôindustrie, Bordeaux, on title and one other leafDibner 112; En fran?ßais dans le texte 179; Horblit 61; Norman 1257; Parkinson p 216

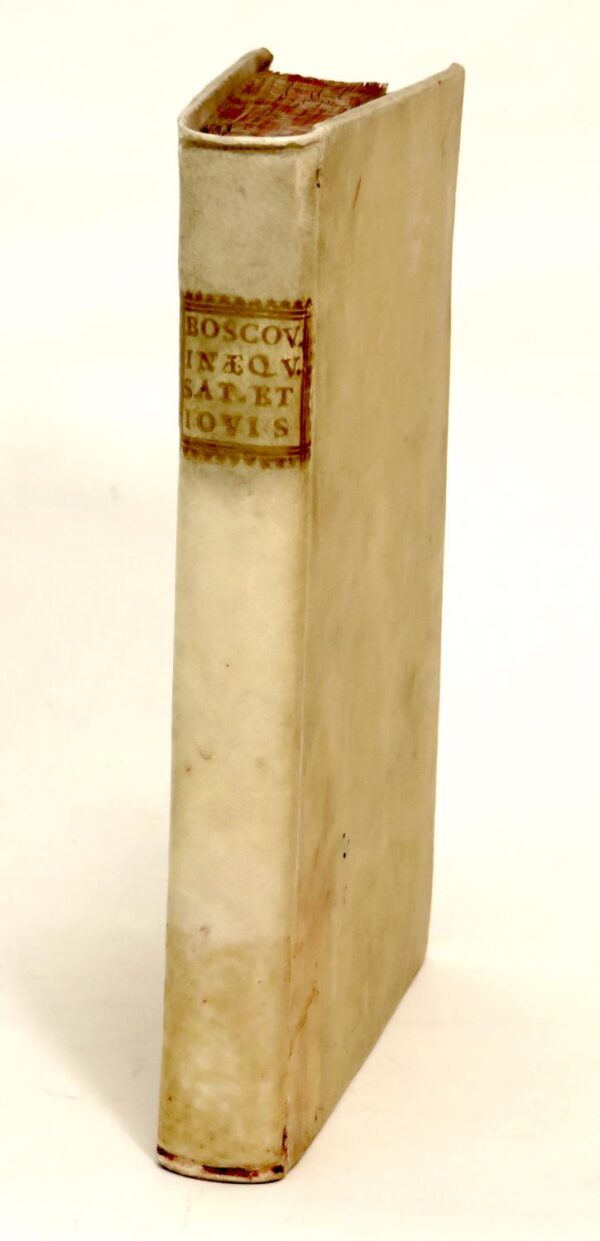

BOSCOVICH, Ruggero Giuseppe] (1711-1787)

4to (200 x 127 mm), pp xxiv 187 [1], with woodcut ornament on title, woodcut initials and headpieces, and four folding engraved plates; a fine copy in contemporary Italian vellum, labelled in gilt on spine. First edition of Boscovich's work on the aberrations observed in the orbits of Saturn and Jupiter from the predicted Newtonian paths. Taking into account the Earth, this was a version of the classic three-body problem of determining the paths of three moving bodies which affect each other's gravitational field, and which has no rigourous algebraic solution, and requires approximation techniques.Isaac Newton had suggested in the second and third editions of his Principia (1713, 1726) that the observed perturbations in the motions of Jupiter and Saturn were a consequence of gravitational interaction, but neither he nor Flamsteed could devise equations to solve the problem. As a result the Paris Académie des Sciences had proposed a competition on solving the problem in 1748, 1750, and 1752, with Clairaut and d'Alembert acting as judges. They awarded the prize to Euler for the years 1748 and 1752, but the 1750 prize remained unassigned. Boscovich had submitted a paper on a proposed solution, which received an honourable mention and was considered for publication in the Mémoires of the Academy, but he wasn't awarded the prize. He decided to expand his paper, the result of which was the present work.Boscovich's approach arose from his study of comets and his method for determining parabolic orbits which, as DSB remarks, 'comes close to the classic method of H.W. Olbers (1797). An interesting treatise of 1749 concerns the determination of an elliptical orbit by means of a construction previously employed for resolving the reflection of a light ray from a spherical mirror. Boscovich employed this method again in 1756, in a treatise discussing the reciprocal perturbations of Jupiter and Saturn, which he entered in a competition on the subject set by the Academy of Sciences in Paris.'Riccardi I.1 179 n 9; Sommervogel I 1840 n 61

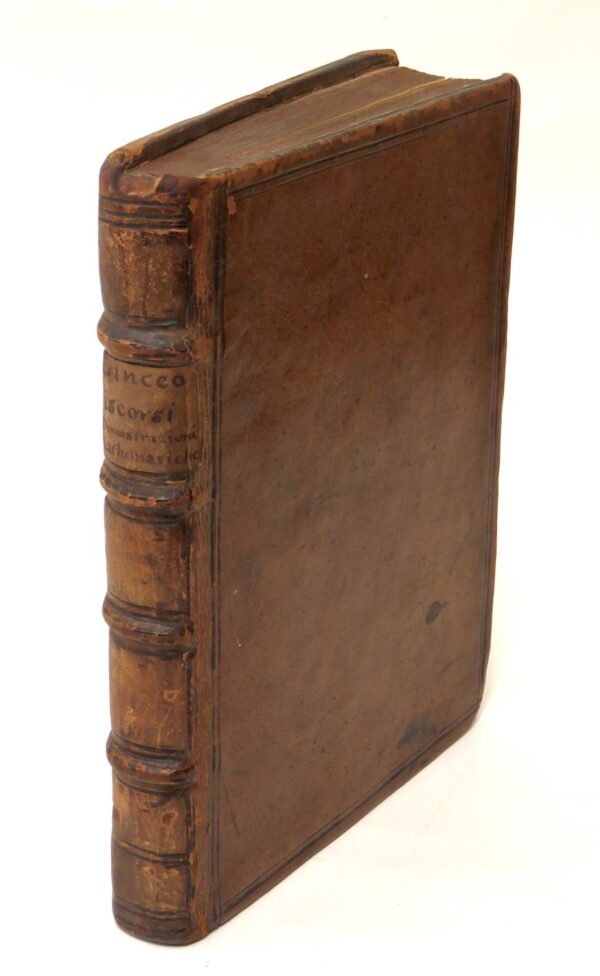

GALILEI, Galileo (1564-1642)

4to (190 x 137 mm), pp [viii] 306 [recte 314] [6], with numerous woodcut diagrams and illustrations in text; a very clean, crisp copy in untouched contemporary English blind-ruled sheep, paper label on spine, hinges slightly rubbed and small chip to head of spine. First edition of Galileo's most important work, the foundation of modern physics.This work was Galileo's 'greatest scientific achievement ? Mathematicians and physicists of the later seventeenth century, Isaac Newton among them, rightly supposed that Galileo had begun a new era in the science of mechanics. It was upon his foundation that Huygens, Newton and others were able to erect the frame of the science of dynamics, and to extend its range (with the concept of universal gravitation) to the heavenly bodies' (PMM 130). 'Unable to publish this treatise on mechanics in his own country because of the ban placed on his books by the Inquisition, he published it in Leyden. Considered the first modern textbook in physics, in it Galileo pressed forward the experimental and mathematical methods in the analysis of problems in mechanics and dynamics. The Aristotelian concept of motion was replaced by a new one of inertia and general principles were sought and found in the motion of falling bodies, projectiles and in the pendulum. He rolled balls down an inclined plane and thereby verified their uniformly accelerated motion, acquiring equal increments of velocity in equal increments of time. The concept of mass was implied by Galileo's conviction that in a vacuum all bodies would fall with the same acceleration. Newton said he obtained the first two laws of motion from this book' (Dibner).The book has a dedication to the Comte de Noailles, French ambassador to Italy, dated Arcetri, 6 March 1638, in which Galileo praised the publishers for their taste and skill. With all his writings banned by the Inquisition, Galileo had given the manuscript to De Noailles with instructions to have it published in Leiden by the Elseviers, to whom Galileo owed a debt of gratitude for the publicity given to his earlier writings, the Latin translations of the Dialogo and Letter to the Grand Duchess Christina published in 1635 and 1636.The binding is a typical 'cheap' English binding of the period, with no pastedowns, leaving the pasteboards showing.Provenance: eighteenth-century engraved Hopetoun bookplateCarli and Favaro 162; Cinti 102; Dibner 141; Evans 27; Horblit 36; Norman 859; Parkinson pp 80-81; PMM 130; Sparrow 75

BOURGEOIS [BOURSIER], Louise (1563-1636)

8vo (167 x 95 mm), ff [12] 12 [recte 3, without terminal blank], with fine engraved allegorical title and two engraved portraits (the author and Marie de Medici, Queen of France); a fine copy, in nineteenth-century French brown morocco, panelled in blind with gilt corner ornaments, spine gilt, slightly worn. First edition, first issue, very rare, of the first obstetrics book written by a woman to be published, and a work that founded obstetrics as a science. It was one of the most popular and influential textbooks of its day, and was credited by Jean Astruc with greatly advancing French midwifery. 'She was one of the pioneers of scientific midwifery; her Observations was the vade mecum of contemporary midwives' (Garrison and Morton).Louise Bourgeois became interested in midwifery after the birth of her first child, with the result that she studied medicine and obstetrics practice under her barber-surgeon husband, Martin Boursier, and his teacher the great Ambroise Paré. The guild of midwives tried to oppose her application for a licence, fearing her increasing reputation amongst Paré's circle of surgeons. Their opposition was of no avail, however, and she was summoned to attend the confinement of Marie de Medici, Queen of France, for the birth of the future Louis XIII. She thus became midwife to the French court for 27 years, and delivered all the children of Marie de Medici. The death by puerperal sepsis of the child of the Duchess of Orléans, the princess Marie de Bourbon-Montpensier, in 1627 brought an end to her reign at the age of 64, and as a result Louis XIV required that at all future royal births a surgeon should be present.Bourgeois drew on the practice of Paré and Guillemeau. She 'advocated the induction of premature labor for contracted pelvis and gave original descriptions of prolapsed umbilical cord and face presentation and their management' (Speert).The collation of this work is a8 e4 A-P8, Q4, with I8 cancelled, with numerous errors in foliation and two in signatures (D3 and E3); the work was reset correcting these errors in the later issue, which can be distinguished by having Q4 blank (or absent)Provenance: presentation inscription on front flyleaf 'Au Docteur L. Santé Amicitior memoria sacrum Langres 1915 Paris [infinity sign] Georges Grappe'; Georges Grappe (1897-1947) was an art historian and curator of the Rodin museumGarrison and Morton 6145; Cutter and Veits pp 73-76; Speert Iconographia gyniatrica pp 72-73; Krivatsy 1625 (imperfect); Waller 1365; OCLC records NLM, UCLA, Yale, Kansas, Johns Hopkins, Duke, Philadelphia College of Physicians, and UBC for North America (both issues, mostly the second)

PETRINI, Giovanni Vincenzo] (1725-1814)

Two vols, 8vo (218 x 145 mm), pp LII 384 [2, errata and blank]; XXXIX [1, blank] 387 [1, blank]; some faint marginal waterstaining to first leaves of second vol, some corners of prelims crumpled, really a very attractive, fresh, and unpressed copy in contemporary Italian patterned boards (differing but both vols with the same provenance), slightly worn. First edition of this extensive catalogue of the mineralogical museum in the Collegeo Nazareno in Rome, founded by the author, Father Petrini and arranged by Scipione Breislak.'Rare. Extensive descriptive collection catalog of the mineral specimens held in at Nazareno College in Rome at the end of the 18th century. The preliminaries of the first volume provide some history of the formation of the collection and a synopsis of the new chemistry of Lavoisier. The catalog then commences, classifying the specimens into a standard structure of salts, earths, bitumens and flammable bodies, and metals. Volcanic objects and fossils are given their own classifications and are treated at the end of volume two' (Curtis Schuh, Biobibliography of Mineralogy online). The organiser of the collection, Scipione Breislak (1750-1826) was '. one of the founders of volcanology in Italy, Breislak was the first to determine that basaltic rocks were of extrusive origin; he also emphasised that the tufaceous deposits of Campania originated under water, and he reconstructed the evolution of Vesuvius' (DSB). He was the author of Introduzione alle Geologia (Milan, 1811).'Antiquarians and polymaths in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries pursued del Riccio's interest in the geological and geographic origins of marble with even greater scientific rigor. The secretary of the papal nephew Francesco Barberini, Cassiano del Pozzo, assembled a vast collection of drawings of the objects, buildings, and other material remains of the ancient world. This corpus of drawings, known as the paper museum (museo caraceo), included a catalogue of stones painted on paper. Dal Pozzo worked with the Venetian painter Jacopo Ligozzi and the director of the opificio fiorentino, Matteo Nigetti, in painting and compiling the samplings. Painted compilations such as Dal Pozzo's became the actual marble-sample panels of the eighteenth century: to this end Father Giovan Vincenzo Petrini (1725-1784) founded a mineralogical museum in the Collegio Nazareno in Rome' (Radical Marble, Architectural Innovation from Antiquity to the Present, J. Nicholas Napoli and William Tronzo, eds)Provenance: early ownership inscription 'C. Guicciardi' on both endleavesWard and Carozzi 1754; OCLC records Smithsonian, Chicago, Illinois, Oklahoma, McGill, and Cornell in North America

CASTELLI, Benedetto (1578-1643)

4to (224 x 160 mm), pp [viii] 79 [1, blank], title with large vignette of the arms of the Medici dedicatee, engraved by Pietro Tedeschi, and five woodcut optical diagrams in text; a fine copy on thick paper, unpressed, in nineteenth-century calf-backed boards, minor wear to spine. First edition of this rare posthumous publication, containing Castelli's most important contributions to the field of optics. The text comprises miscellaneous pieces, including the first publications of two letters to Galileo (dated 27 June 1637 and 2 August 1638, pages 47-79) detailing experiments on the absorption and transmission of radiant heat by differently coloured surfaces.'Castelli's optical investigations were continued in a treatise sent to Giovanni Ciampoli in 1639 and published in 1669 [in the present work]. Included are many observations and conclusions with respect to the persistence of optical images, by which Castelli explained the perception of motion, the illusion of forked tongues in serpents, and other phenomena. In the same treatise he recommended the use of diaphragms in telescopes to impede transverse rays, anticipating Hevelius. His discussions of the camera obscura, the inversion of images on the retina, and of cataract (from which Galileo had recently lost his sight), although less novel, are not without interest.'More celebrated is Castell's discussion of heat in a series of letters to Galileo (1637-1638) and particularly his experiments with the absorption of radiant and transmitted heat by black and white objects. Two of these letters, in which the pursuit of experimental science is even more clearly described than in Galileo's work on bodies of water, were published in 1669 [in the above]' (DSB).In a treatise on the preservation of grains (pp 39-46) Castelli suggests keeping wheat in sealed containers so that pathogens are kept out, anticipating later discoveries by Francesco Redi in microbiology and the discrediting the theory of spontaneous generation.Carli and Favaro 322; Riccardi I 291 n 3; OCLC records Cal Tech, Huntington (Burndy), Yale, American Philosophical Society, Oklahoma, Wisconsin, and UC Berkeley for North America

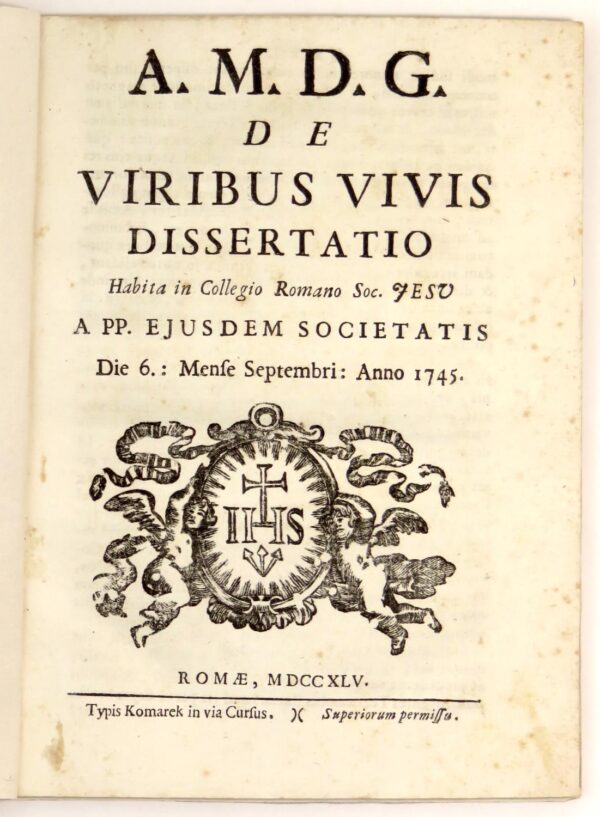

BOSCOVICH, Ruggero Giuseppe] (1711-1787)

4to ( 221 x 164 mm), pp XLIX [1, blank], with folding engraved plates; a very faint occasional marginal spotting, a very good copy in plain wrappers.First edition, first issue of Boscovich's earliest published work on his dynamic point theory, and which was the precursor to his great Philosophiae naturalis theoria redacta ad unicam legem virium in natura existentium (1758), a work considered as the 'birth of atomic physics' and praised by Faraday, Maxwell, and Heisenberg. Boscovich stated in the Philosophiae naturalis theoria that his work originated in this 1745 publication.Boscovich's dynamic point theory 'was not only the first general mathematical theory of atomism . but more specifically it was the first scientific theory: to treat all the ultimate constituents of matter as identical; to employ finite numbers of point particles; to eliminate Newtonian mass as a primary quantity, substituting a kinematic basis; to postulate a relational basis for the mathematical treatment of inertia and of all space and time observations; to propose to derive all physical effects from a single law; to eliminate the scale-free similarity property of the Newtonian law, introducing natural lengths into continuous laws so as to determine unique equilibrium positions and other scale-fixed properties; to employ a power series to represent an observable.' (L. L. Whyte in Roger Joseph Boscovich . Studies of his life and work, London, 1961).'The Theory of Natural Philosophy is now recognized as having exerted a fundamental influence on modern mathematical physics . As the title of his book implies, he considered that a single law was the basis of all natural phenomena and of the properties of matter; that the multiplicity of physical forces was only apparent and due to inadequate mathematical knowledge' (PMM).Boscovich's 'heterodoxy in mechanics began to be apparent at least as early as 1745, when he published an important discourse on the subject of living force (vis viva) . This discourse contained the first statement of Boscovich's universal force law.'That law was inspired partly by Leibniz's law of continuity and partly by the famous thirty-first query with which Newton concluded the fourth edition of his Opticks. There Newton raised speculatively the question whether there might not exist both attractive and repulsive forces alternately operative between the particles of matter. From this idea Boscovich proceeded by way of an analysis of collision of bodies to the enunciation of a "universal law of forces" between elements of matter, the force being alternately attractive or repulsive, depending upon the distance by which they are separated. As that distance diminishes toward zero, repulsion predominates and grows infinite so as to render direct contact between particles impossible. A fundamental role is played by the points of equilibrium between the attractive and repulsive forces. Boscovich called such points "boundaries" (limes, the Latin singular). Some of them are points of stable equilibrium for the particles in them and others are points of unstable equilibrium. The behavior of these boundaries and the areas between them enabled Boscovich to interpret cohesion, impenetrability, extension, and many physical and chemical properties of matter, including its emission of light.Extended description upon requestThere are two issues of this publication, an academic one as here, and a commercial one, the latter containing a differing imprint and also naming Boscovich as the author. A comparison of the two makes clear that both were printed from the same standing type, apart from the title page. The commercial issue has the imprint 'Sumptibus venantii Monaldini bibliopole', and also a different title ornament.Manuscript corrections to the text on pages V, IX, and XXXIX, as in the BSB copyRiccardi I.1 174 n 21; Sommervogel I 1832 n 22; OCLC records Huntington, Smithsonian, American Philosophical Society, Harvard, Princeton, and Brown for North

![Theorie de la Perspective [with:] Nouvelle Theorie du Melange des Coulêurs. Tirée de l'Optique de M. Newton . [Paris](https://rarebookinsider.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/30623450518-600x853.jpg)