China Monumentis Qua Sacris quà Profanis, Nec non variis Naturæ & Artis Spectaculis, Aliarumque rerum memorabilium Argumentis Illustrata, Auspiciis Leopoldi Primi Roman. Imper. Semper Augusti Munificentissimi Mecænatis

Complete with the engraved title page, a full-paged portrait of Kircher, 2 large folding engraved maps of China, 59 text engravings, and 23 full-paged engravings (one of which is a large folding reproduction of the "Nestorian Stele"), including some drawn by the artist Willem van der Laegh. This is a fine copy, bound in contemporary stiff vellum (lightly soiled.) The text and plates are crisp and mostly bright, with some light foxing or browning to scattered leaves, and a few clean tears, without loss (lvs. K2, L4, S1); natural paper irregularities to the margins of 2 plates (at p. 113 and p. 155), not affecting the image. This copy features a variant of the engraved title that states that this edition was printed at Amsterdam in 1667 "Vidua Elizei Weyerstraet", that is, by Sara Weyerstraet, widow of one of the original publishers, Elizaeus Weyerstraet (who died in late December 1666.) However, this is in fact the Antwerp counterfeit printed by Meursius in 1667, the engraved t.p. of which usually indicates Meurs and Antwerp as the publisher and place. "In 1667 the learned German Jesuit, Athanasius Kircher, published his 'China Illustrata' at Amsterdam. Gathering his materials from the works of other members of the Society, Kircher wrote one of the century's most influential treatises on China. His primary purpose was to establish the authenticity of the Nestorian monument discovered in Sian, and to that end he produced in print the original Chinese and Syriac inscriptions on the monument, the Chinese text in Romanization, and finally a Latin translation and his explication of the Chinese and Syriac texts. In addition, Kircher included a sizeable description of China and other places in Asia. For example, in a section devoted to the various routes to China and the history of Christianity in China, he sketched all the old overland routes, including that of Johann Grueber and Albert d'Orville from Agra to Peking, as well as giving a description of Tibet. He traced the activities of Christians in China from the tradition of St. Thomas to Boym's reports about the conversions at the Ming pretender's court and Adam Schall's experiences at the Ch'ing court during the K'ang-his era. Following what he thought to be the spread of idolatry from the Near East to Persia, India, and finally to East Asia, Kircher described the religions of China, Japan, and India. His extensive discussion of Hinduism and the Mogul Empire derived from the letters of Heinrich Roth (1620-68), his fellow Jesuit. There are several chapters on government, customs, geography, fauna, flora, and mechanical arts of China, and a very interesting scholarly discussion of the Chinese language, which indicates that Kircher had made considerable progress in it. There is a long Latin-Chinese dictionary, and Finally Father Johann Grueber's (1623-80) responses to a long series of questions posed by the duke of Tuscany. Kircher's volume contains several beautiful pictures taken from Chinese and Mughul originals which Grueber brought back to Europe with him in 1664." (Lach pp. 485-486) "Although the "China Illustrata" was not the product of Kircher's own experience in China, it was frequently used or cited as a source of information y later writers. Some of the information contained in it, for example the text of the Nestorian monument, Roth's description of Hindu religion, and Grueber's description of Tibet, had not appeared in print before. "Roth's contribution to Kircher's work includes a description of the ten transformations (avatars) of Vishnu and several illustrations of Indian provenance, as well as a discussion of the Sanskrit language which is illustrated with five plates presenting examples of Sanskrit writing. Roth returned to Europe in 1662 accompanied by Grueber, who with Father Albert d'Orville had journeyed overland from Peking to Agra by way of Lhasa. In the busy years after his return to Europe, Grueber evidently tried to write a description of Tibet and f his journey across the Himalayas. Apparently he never finished it. He may have sent parts of it to Kircher, however; he wrote several letters to Kircher and apparently sent him some of his sketches, all of which formed the basis for a description of Tibet and of Grueber and d'Orville's journey in the "China Illustrata"-probably Europe's earliest account of the Tibetan capital. Kircher's account also contains eleven very interesting plates made from Grueber's sketches, including one of the Dalai Lama and one of the Potala Palace in Lhasa which was frequently reproduced and served as Europe's only glimpse of Lhasa for the following 250 years."(Lach pp. 527-528) "China Illustrata'' was in many ways [Kircher's] most significant work historically, being the first publication of important documents on oriental geography, botany, zoology, religion and language. Kircher admits in the preface that his main concern was to preserve the fruits of his colleagues' efforts, collected with so much effort and privation, and sometimes at the cost of their very lives. Foremost among his sources were Johann Adam Schall; Bento de Goes, who in 1602 had left from the Jesuit station in Agra, north India, to find a land route to China and seek the fabled land of Cathay; Kircher's former pupil Martin Martini, appointed mathematician to the Chinese Imperial Court and author of 'Novus Atlas Sinensis' (1655); and the trio of intrepid explorers Johann Grueber, Michael de Boym and Heinrich Roth, who all returned to Rome in 1664. Grueber, whose return journey had taken three years, and led him through Tibet, modern Pakistan, Iran, and Turkey, was an accomplished draughts man and supplied the originals for many of 'China's' topographical engravings. Boym provided those of Chinese flora, and transcription of Chinese characters that enabled Kircher to publish the first vocabulary of the language. Roth, who traveled with Grueber, had already become adept in Sanskrit, of which he compiled a dictionary. Here

More from Liber Antiquus Early Books & Manuscripts

Glorias de Queretaro en la nueva congregación eclesiástica de María santísima de Guadalupe y en el sumptuoso templo, que dedicò à su obsequio d[on] Juan Cavallero, y Ocio presbytero, comissario de Corte del Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisicion. [with, as issued] Primavera Indiana. Poema Sacro-histórico. Idea de María Santísima de Guadalupe de Mexico. Copiada de Flores

Bound in modern blind- and gilt- stamped calf, spine gilt in compartments. With the author's (not the printer's) woodcut Pegasus device on the title page. A very good copy with some cosmetic defects: marginal damp stain to the first three leaves, small repair at lower outer margin of half title, and dark stains to the upper right corner of some leaves in the second work. Early inscription scored through; 20th c. (1911) private collector's stamp of Jorge Demetrio Casasús y Altamirano (d. 1964). Extremely rare. I have traced 2 copies in the U.S: UT Austin and JCB. First edition, extremely rare, of this remarkable book printed by Paula Benavides, celebrating the establishment of the congregation and church of Santa Maria de Guadalupe in Querétaro, Mexico. The book describes the festivities held during the dedication of the church, a description of the church itself, the story of the Virgin's first miraculous appearance in Mexico, and the Indigenous history of the region. "Polymath" is the term most often applied to the author, Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (1645-1700), a cosmographer, philosopher, chronicler, poet, historian, cartographer, former Jesuit (he was expelled for bad behavior) and -in his time- the foremost authority on pre-Hispanic Mexican history, fluent in Nahuatl. Sigüenza and his contemporary Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz are considered the two principal intellectual figures of the Mexican Baroque. Sigüenza's description of the festivities includes detailed accounts of the bullfights, poetry contest, and an elaborate costume parade (máscara) with Indigenous participants, including Chichimec Indians, their bodies painted with red clay, and troops of dancers performing the famed Aztec ceremonial dance, the tocotín, accompanied by floats and figures representing Aztecs deities and monarchs, the Virgin of Guadalupe herself, and the mountain on which she first appeared. Sigüenza's elaborate description of the parade has been called "perhaps the most complete account of a [Mexican] máscara made during the closing decades of the seventeenth century."(Leonard) Glories of Querétaro: "'Two exquisite arches . . . formed a canopy over a fluted shell supported by a pair of Persian caryatids. Beneath the shell, the Image of the Virgin of Guadalupe rested on her canopied throne. Steps covered in silk descended from the throne, and pennants of colored taffeta embellished the ensemble . . . . On the bottom step leading up to the throne knelt an exquisite young girl clad in indigenous finery who symbolized all of America, and, even more so, these Septentrional Provinces, called Anahuac in pagan days. Her hands bore a heart--the heart of all--and an incensory that dispensed fragrances and sweet aromas.' So writes the preeminent seventeenth-century Mexican intellectual, Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora, in 'Glories of Querétaro' (1680) of a float the Indians contributed to the festival inaugurating a church that honored the Virgin of Guadalupe. "'Glories of Querétaro' chronicles the arduous process of founding the Ecclesiastical Congregation of Querétaro, which became colonial Mexico's second most important church dedicated to the Virgin of Guadalupe after the shrine in Tepeyac. Yet 'Glories' is more than a chronicle--it holds keys to an era. In Sigüenza's text, readers will find dynamic articulations of the spiritual, political, and cultural issues that to a significant extent drove colonial Mexico and even the Hispanic New World in general. Beyond the theology and cult to the Virgin of Guadalupe, they include: full-bodied accounts of New World festivals, the indigenous past and present, creole patriotism and cultural nationalism, colonial cities, evangelization, the tangles of New World religious and civil politics, and some touches of colonial satire. Querétaro itself holds particular interest as a contact zone and exceptionally multicultural city in which Indians and creoles lived side by side."(Merrim, "The Glories of Querétaro: Chronicle of an Early Mexican Church Honoring the Virgin of Guadalupe. Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora", 2015) The Description of the Church: "Chapter Six describes the architecture of the church [attributed to the architect] José de Bayas Delgado], the composition of its altars and altarpieces, and the jewels donated by its patron. The self-stated 'inventory' catalogs the new church and its furnishings minutely, using technical terminology drawn from architecture and mathematics. Architecturally, the new church featured two chapels (with the unfinished towers that led to a disaster recounted in Chapter Seven); a residence and school, appended to the main building; cupolas and cross-vaulted domes made of mosaics and frescoes; and impressive portals of cedar framed by Corinthian and Doric columns. Its internal space was configured by ornate columns in all the classical styles plus those typical of the Baroque: the intricate, highly adorned Solomonic and estípite columns. A painting of the Virgin of Guadalupe by Mexican artist Baltazar de Echave the Third constituted one centerpiece of the new church. Don Juan Caballero de Ocio, who financed the entire church, also contributed the luxury ornaments and vestments that furnished it, including objects from Mexico, Italy, and Egypt."(Merrim, p. 58) The use of Nahuatl in the "Glorias de Querétaro" Sigüenza's account is rich with Nahuatl words, especially in the descriptions of Native costumes, dances, and musical instruments. Their inclusion adds another layer of ornateness to Sigüenza's Baroque diction and imagery, and he admits this sort of extravagance might annoy his readership: "Xiuhzolli, the insignia of royalty, adorned all of the Indians' heads, each of which became the noble repository of many rich gems that had traveled from the east, source of their luster, to reveal their true brilliance in these provinces of the west. The Indians' venerable headdresses, peak of their finery, boasted malacaquetzalli, clauquecholtontec andSalmacis, Lyrian & Sylvia, Forsaken Lydia, the Rape of Helen, a Comment thereon with Several other Poems and Translations

A very good, crisp copy, complete with the etched frontispiece, bound in contemporary sheepskin (spine repaired, some surface abrasion, mild wear to extremities). Minor blemishes as follows: light dampstain to leaves B6-7 and gathering G; small, light stains on leaves D1, E, G8. A few other scattered blemishes. Margins of final three gatherings with light soiling. The book was reissued in the same year under the title "Poems and Translations, amorous, lusory, morall, divine". First edition of Sir Edward Sherburne's translations of several French and Italian poems on classical themes: "Salmace" by Girolamo Preti (1582-1626), "Lidia abbandonata" by Giambattista Marino (1569-1625), and "Metamorphose de Lyrian et de Sylvie" by Marc Antoine Gérard (1594-1661). The book also includes Sherburne's translation of "á¼ÏÏαΠὠá¼Î»ÎνΠÏ" ("The Rape of Helen") an epyllion by the late Roman age poet Colluthus of Lycopolis (fl. 500). Sherburne was encouraged in his poetic efforts by the poet and classical scholar Thomas Stanley, to whom this volume is dedicated. The fine etched frontispiece shows four scenes illustrating the main works, including Helen being taken aboard Paris' ship; and Lyrian turning into ivy and twining around Sylvia, who has been transformed into an elm.La caduta del regno dell’Amazzoni. Festa teatrale fatta rappresentare in Roma dall’Ecc. Signor Marchese di Coccogliudo per le nozze di Carlo II Re delle Spagne e della Principessa Marianna Contessa Palatina del Reno

Bound in contemporary sprinkled calf, spine richly tooled in gold, red Morocco label, gilt, in second compartment (binding with light wear, corners bumped.) A nice copy, complete with all 13 plates (a number of copies have only 12.) The work is extremely rare. I have located only 3 copies in North America (Morgan, Harvard, National Gallery of Art). Scattered light stains and light soiling to text and plates. Blemishes to leaves C3-4 and G2-3, private collector's stamp in margin of leaf D1, the same stamp removed from the verso of the title, short marginal tears to lvs. E2-3, not touching the text. The plate at p. 49 with repaired split at fold (slight separation), light wear to fold of plate at p. 51, repair to leaf K4 with loss to two words in the penultimate line. "The Fall of the Kingdom of the Amazons", with a libretto by Domenico de Totis and music by Bernardo Pasquini, was based on Solìs y Ribadeneyra's "Las Amazonas". The production was undertaken at the behest of the Spanish ambassador in Rome, Luis Francisco de la Cerda, to celebrate the wedding of King Charles II of Spain and Marianna of Neuberg, daughter of the Elector Palatine. The opera was staged in the magnificent theater within the Palazzo Colonna, which reached the apex of its virtuosismo spettacolare with this production, on 15 January 1690. The "Caduta" is an excellent example of a "festa teatrale", an opera, with dances, divided into acts, with mythological themes and characters, produced for a noble audience. The elaborate sets, complete with dazzling floats (carri) and flying creatures, were designed by Girolamo Fontana (1665/68?-1701). Fontana designed the sets in such a way that one seemed to transform into another. For example, a beach surrounded by rocky crags morphs into a cave within which one of the protagonists is trapped. When the hero manages to dig a hole in the wall of the cave, the side of the cave slides aside to allow him egress, and he emerges from the gloomy cave (which is illuminated by a small lamp), into an open field bathed in sunlight. A number of scenes from the performance, including the fantasy "The Walnut Tree of Benevento", are beautifully reproduced in 13 magnificent plates (described below), engraved by Alessandro Specchi (1668-1729), Giovanni Francesco Venturini, Luzio Bonomi, Francesco Buffettini, and Pietro Paolo Petrucci. For a detailed discussion of the opera, see Andrea Garavaglia, "Il mito delle Amazzoni nell'opera barocca italiana" (2015), p. 183-197. For a discussion of the stage sets, see: Tamburini, Il Teatro a Roma (1997), Vol. II, p. 640-661) Plate 1: Prologue: A beach, surrounded by crags, with a view of the sea. At center stage stands Hercules conversing with Atlas, who has fallen on the beach with the globe of the Earth, divided into four parts, upon his shoulders. [incisione: G. Fontana] Plate 2: Prologue: The same beach. From the sea emerge three chariots, laden with gold, silver, precious gems, coral, crystal, and flowers. The first is pulled by hippocampi and surmounted by four Americans. The second is drawn by dolphins and carries Africans. The third is drawn by taurocampi (bull-headed hippocampi). On the beach, Hercules in conversation with personifications of Asia, Africa, Europe, and America. [engraved by Specchi] Plate 3: Act 1, Scene 1: In a dark grotto, Artide, son of Alexander the Great, tries to pry away some of the rocks in the wall to escape. On the table in the foreground, an oil lamp, some books, and a globe. [engraved by Venturini] Plate 4: Act 1, Scene 1: Artide emerges into an open clearing bathed in sunlight and surrounded by trees. In the background flows the river Termodon. Turpino, squire of King Sarmander of Sarmatia greets him. In the forest to the right, the king's army. As the scene progresses, the sun shines more brightly. [engraved by Venturini] Plate 5: Act 1, Scene 9: Artide accompanied by soldiers, Sarmatians, and Turpino dressed as a woman, all in an elaborate architectural stage set with caryatids and an arch, visible in the background. [engraved by Petrucci] Plate 6: Act 1, Scene 12: An ornate hall with a magnificent bed in the shape of a shell set in an alcove. In the scene: Mandane, queen of the Amazons, Mitiline, the queen's sister and general of the Amazonian army, Idaspe, Artide's guardian, and Tisbe, the queen's lady-in-waiting. [engraved by Bonomi] Plate 7: First intermezzo: A large garden with spallieri, statuary, and elevated, projecting loggias. At center stage, at the top of a grand stairway, sits Venus on a shell-shaped throne, attended by cherubs. In the foreground, other cherubs perform a dance, while in the sky above still more of them flit about brandishing bows and arrows. [engraved by Fontana(?)] Plate 8: Act 2, Scene 6: Another beautiful garden with statuary and fountains. [engraved by Bonomi] Plate 9: Act 2, Scene 14: Mandane and Licandro in a large, ornate gallery. [engraved by Fontana(?)] Plate 10: Second intermezzo: A surreal scene unfolds at the "Walnut Tree of Benevento": a flying goat carries Turpino, transformed into a bat-winged bear, to the grove of Benevento, while other fantastic beasts fly about. Below, in a garden setting, "various ridiculous monsters" perform dances while satyrs, medusas, and naked caryatids frolic, forming twisted, living columns surmounted by dragons. In a glass bottle in the foreground is a gestating homunculus. In the background, under the tree, satyrs sit on wine casks. [engraved by Fontana(?)] Plate 11: Act 3, Scene 1: Mitilene in full armor and her sister the queen stand in a regal colonnade with a lively fountain. [engraved by Bufalini] Plate 12: Act 3, Scene 7: A large, bejeweled room, richly decorated with embroidered panels, paintings, and vases of alabaster. [engraved by Specchi] Plate 13: Act 3, Scene 14: The armies of the Sarmatians and the Amazons , led by their sovereigns, burst forth from their tents into an open plain. In the sky above, "Fame" rides in a chariot drawnTheatrum crudelitatum hæreticorum nostri temporis. Editio altera emendatior

Illustrated with 29 engravings of torture and execution, an engraved title page vignette, and numerous printer's ornaments. A very fine, fresh copy in original stiff vellum (lightly soiled, corners bumped, upper hinge starting at foot, remains of one silk tie.) The contents are in excellent condition, the impressions of the engravings rich and sharp, with a few minor faults: dog-earing to upper outer corner of first ten lvs., short marginal tears to outer margin of lvs. I1 and Mm4, a few very trivial marginal blemishes. This copy was bound interleaved with blanks, presumably for adding the names of additional martyrs. The leaf following p. 59 has the names of other murdered priests and the manner of their martyrdom. Fourth edition (1st 1587) of Verstegan's extraordinary graphic account of atrocities committed against Catholics in England under Henry VIII, by the Calvinists in England and Ireland under Elizabeth I, in France at the hands of the Huguenots, and in Belgium by the Gueux (i.e. the "Sea Beggars") during the 1560s and 1570s. There is an account of the 40 Jesuit martyrs, led by Ignazio de Azevedo, who were murdered by Calvinist pirates at sea on their way to Brazil in 1570. The "Theatrum" is illustrated with 29 large engravings depicting the grisly tortures and executions endured by Catholics at the hands of their tormentors. The work opens with the beheadings of Sir Thomas More and Bishop John Fisher and concludes with the beheading of Mary Queen of Scots. "Latin verses under the illustrations, and some preliminary verses, were provided by 'I.B.', identified by Wood as 'one Joh. Bochius.' This Johannes Bochius was a Catholic loyalist who had been appointed secretary to Antwerp's city council in 1585. The publisher was Adrian Huberti, like Verstegan himself a 'printer' without a press, and the printing seems to have been carried out by Christopher Plantin, Typographer Royal. [suggesting] that it may have been an unofficial work of government propaganda. "The 'Theatrum' was in five sections: an introduction and illustrated accounts of the persecution of Catholics during the reign of Henry VIII, during the French Wars of Religion, in the early years of the Dutch Revolt, and under Elizabeth I. It was to be a seminal work of hagiology, but it was not only an important devotional work, it was also, if only indirectly, propaganda for the Spanish Armada. The book ends with the depiction of the execution of Mary Queen of Scots on 8 February 1587, and a call to the Catholic princes of Europe to avenge this Calvinist regicide, while the introduction devotes considerable space to demonstrating that Elizabeth I had broken her coronation oath and violated reason and justice with her various statutes and proclamations against Catholics. "A stated purpose was to show that Calvinists, unlike any other Christian group since the Münster Anabaptists, viewed the forcible overthrow of the established order as a necessary precondition to religious reform in the creation of a 'godly commonwealth'. Both as a devotional work and as propaganda, the 'Theatrum' far surpassed the immediate purpose of the moment and continued to be reprinted into the 1600s. It was of iconographic importance into the 17th century. Almost a century later, Anthony à Wood was to write of the 'Theatrum' that 'Tis very scarce, and sells for any money.'"(Arblaster, Antwerp & The World: Richard Verstegan and the International Culture of Catholic Reformation, p. 41-2) "Richard Rowlands alias Verstegan, antiquary, born in the parish of St. Catherine, near the Tower of London, was grandson of Theodore Roland Verstegen, of an ancient Dutch family which was driven from Gelderland to England about 1500. His father was a cooper. Rowlands, after a good education, was entered at Christ Church, Oxford, in the beginning of 1565 as 'Richard Rowlands, servant to Mr. Barnard'. A zealous Catholic, he declined the tests essential to a degree, and left the university without one. While there, however, he distinguished himself by his study of early English history, and began to learn Anglo-Saxon. Soon 1576, Rowlands removed to Antwerp, dropped his English name, and resumed the paternal Verstegen. He set up a printing press, wrote books, and, being an artist of no mean skill, engraved some of the cuts for them himself. He also acted as agent for the transmission of catholic literature (some of which he printed), and letters to and from England, Spain, Rome, and the Netherlands. He was in frequent correspondence with Cardinal Allen and Robert Parsons, and for a time in their pay."(DNB) "When Verstegan reached Antwerp early in 1587, he found a city in which Catholicism was being re-established and the visible effects of two waves of iconoclasm were in the process of repair. The first violent assault by the Protestants, in August 1566, had been followed by a more deliberate systematic and orderly removal of images from the churches by the Calvinist town council in 1581. The images of martyrdom in reconstructed altarpieces and church ornaments, and in the new works which had been commissioned to replace those destroyed, were different from their predecessors: torture and instruments of torture were now graphically depicted in pictures teeming with detail. It was within this broken religious landscape and in explicit representation of martyrdom, which was to have such a strong influence on his next work, that Verstegan established himself."(Dillon, Theatrum Crudelitatum: The Theatre of Cruelties) "[His] narrative of Elizabeth's treatment of the Catholics of England excited the attention of the English ambassador, and he was thrown into prison. Upon his release he returned to Antwerp and reprinted the book. He was back in France in 1595 on his way to Spain, where he had an interview with Philip, and spent some time at the catholic college in Seville. At the end of the same year he was once more in Antwerp, living 'near the bridge of the tapestry makers,' andDante. Con Nuove et Utili Ispositioni

A charming copy in 18th c. sprinkled calf, gilt, the boards ruled in gold and with small tulip tools at the corners; spine ruled and tooled in gold with charming elephants in the compartments (wear to the spine with loss of some gilding, label ("DANTE") chipped affecting the "N", upper hinge starting. The text is in fine condition. Title page with Rouille's printer's device and "DANTE" in a woodcut compartment; 3 full-page woodcut illustrations (at the opening of "Inferno", Purgatorio", and "Paradiso", and a woodcut medallion portrait of Dante in profile on leaf A3 verso. Guillaume Rouille's edition of 1551 -which this edition follows- was the first edition of Dante to be printed in France. The book includes the commentary of Alessandro Vellutello (1473-1550), first printed in 1544. The first illustration show Dante fleeing from the lion, leopard, and wolf that block his way out of the dark woods. Virgil, Dante's guide on his journey through Hell and into Purgatory, approaches from the background. The second shows Dante and Virgil (having emerged from the Inferno) at the foot of Mount Purgatory, where they encounter Cato, who bids Virgil to wash the filth of the Inferno from Dante's face and to dispel the mist that clouds his eyes. The third woodcut shows Beatrice, Dante's beloved and his guide in the Paradiso, explaining the universal order to Dante. SECOND ROUILLE EDITION (a reprint of the 1551 edition.).Dioptrice seu demonstratio eorum quae visui & visibilibus propter conspicilla non ita pridem inventa accidunt. Praemissae epistolae Galilaei de iis, quae post editionem Nuncii Siderii ope perspicilli, nova & admiranda in coelo deprehensa sunt. Item Examen praefationis Joannis Penae Galli in Optica Euclidis, de usu optices in philosophia

Bound in contemporary vellum, manuscript title to spine (slightly worn, lightly soiled, small loss to spine). A very good copy with intermittent foxing and a small stain to the upper margin. A slim worm-trail has been discreetly filled in the upper blank margin of the opening leaves. 17th c. owner's inscription to title-page. Complete with the errata leaf and the leaf added after p. 26 referring to 'propositio' LXIV. First edition of the foundation work that "changed the course of optics"(DSB), containing both the first accurate theory of lenses and the formation of images by the eye. The book is a direct result of the recently published "Sidereus Nuncius" (1610), in which Galileo announced his observations made with the telescope, among them that the Moon, thought to be smooth, was in fact mountainous and craggy; and that Jupiter had moons of its own. "In order that the enormous possibilities harbored in [the telescope] could develop it was necessary to clear up the theoretical laws by which it worked. And this achievement was reserved solely for Kepler. With the energy peculiar to him, inside of a few weeks, in the months of August and September of 1610, he composed a book tracing basically once and for all the laws governing the passage of light through lenses and systems of lenses."(Caspar) The book also contains Kepler's description of his own modified version of the telescope, known to us as the "astronomical" or "Keplerian" telescope (see below.) In his preface, Kepler discusses the further discoveries that Galileo had made with his telescope subsequent to the publication of his "Sidereus Nuncius", and includes four letters by Galileo, dated 13 October 1610, 11 December 1610, 1 January 1611, and 26 March 1611, which he sent to Kepler via the Medici ambassador at Prague. These new Galilean discoveries include his observations that Saturn is not a single orb, but rather three orbs close together (the telescope was too weak to clearly reveal the planet's rings); and that Venus has phases and reflects the Sun's light (rather than generating its own), which evidence proves that Venus orbits the Sun. "[Kepler's 'Dioptrice'] is divided into 141 theorems which are distinguished as definitions, axioms (theorems needing no proof), problems (theorems to be proved by experiments), and propositions (theorems which follow out of definitions and axioms by logical conclusions). "The author begins with the law of refraction which, indeed, he was here as little able to express exactly as in his earlier work about optics. Since in the 'Dioptrice' however, only small angles of incidence are dealt with, he managed well by assuming the proportionality between the angle of incidence and that of refraction. He himself determined the ratio by measurements. By investigating the path of a ray in a glass cube and three-sided prism he discovered total reflection. "Next in his exposition comes the treatment of the double-convex converging lens. He sets to work with great thoroughness. There appear the ideas well known to us of the real and virtual, the upright and inverted image, the distance of the image and the object, the magnification or reduction of the image. From the path of the ray for a simple lens he proceeds to two- and three-lens systems. In problem eighty-six in which he shows 'how with the help of two convex lenses visible objects can be made larger and distinct but inverted' he develops the principle on which the so-called astronomical telescope is based, the discovery of which is thus tied up with his name for all time. "Further on follows the research into the double concave diverging lens and the Galilean telescope in which a converging [convex] lens is used as objective and a diverging [double concave] lens as eyepiece. By the suitable combination of a converging lens with a diverging lens in place of a simple object lens he discovers the principle of today's so-called telescopic lens by which an inverted real image of an object can be produced, an image which is in fact larger than that formed by a converging lens alone. Even this scanty account of the main content shows the epoch-making significance of the work. It is not an overstatement to call Kepler the father of modern optics because of it."(Caspar, Kepler, p. 198-199) The Keplerian vs. Galilean telescope: Whereas the Galilean telescope consisted of a convex convergent lens as the objective (the lens that forms the image) and a double-concave divergent lens for the eyepiece, the telescope proposed by Kepler used two convex lenses. Although Kepler's version produced an inverted image, it had a larger field of view and higher magnification than the Galilean version. "In any telescope system the objective (which gathers light to form the image) - even when made up of several elements, both converging and diverging - must always be converging as a whole. The Galilean and the Keplerian telescopes thus differ only in the eyepiece, which is diverging in the former, converging in the latter. "The Galilean telescope consists of a converging lens (plano-convex or biconvex) serving as objective, and a diverging lens (plano-concave or biconcave) serving as eyepiece. The eyepiece is situated in front of the focal point of the objective, at a distance from the focal point equal to the focal length of the eyepiece. Since converging lenses are conventionally positive (or of positive optical power) and diverging ones negative (or of negative optical power), we can also say that the distance between the objective and the eyepiece is equal to the algebraic sum of their focal lengths. The negative eyepiece intercepts the converging rays coming from the objective, rendering them parallel and thus forming, to the infinite (afocal position), a virtual image, magnified and erect. The magnification of the system is determined by the ratio between the focal length of the objective and that of the eyepiece. The Galilean telescope, although it furnishes erect imMuséum Regium, seu catalogus rerum tam naturalium, quam artificialum, Qvæ In Basilica Bibliothecæ Augustissimi Daniæ Norvegiæq[ue] Monarchæ, Friderici Qvarti, Havniæ asservantur, Gloriosissimæ Memoriæ Rege, Christiano Qvinto, regnante, Ab Oligero Jacobæo, Med. & Phil. Prof. Regio qvondam describtus, nunc verò magna ex parte auctior uberioribusq[ue] commentariis, præsertim autem qvoad Antiqvitates Historiamq[ue] Numismatum Danicorum, illustratus, accurrante Johanne Lauerentzen, Assessore Consistorii Havniensis Regio

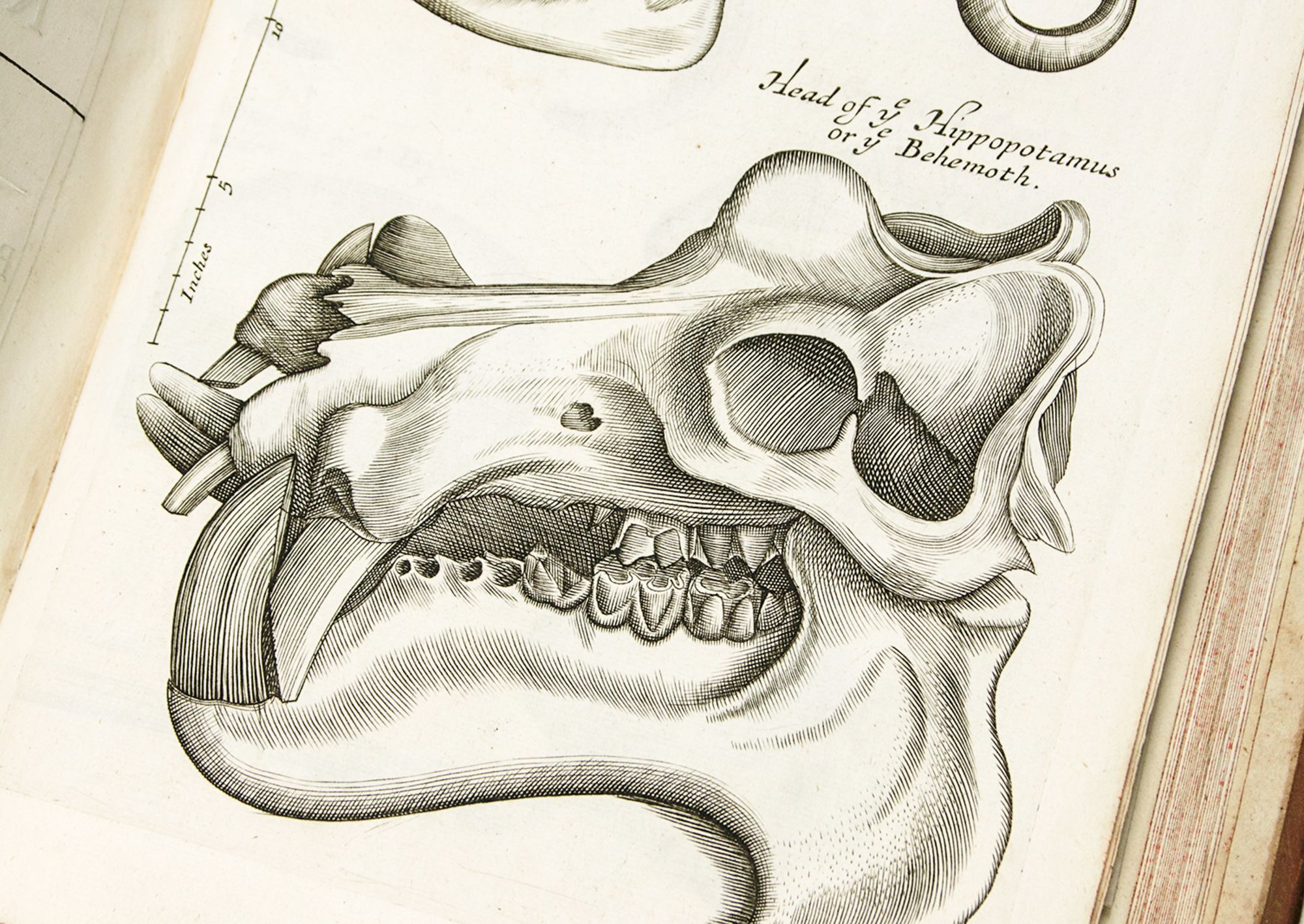

An excellent copy in contemporary sprinkled, paneled calf (minor wear to extremities, discreet repairs to heads of the hinges, very small defect to headcap), the boards with a decorative gilt filet at the edges, the central compartment framed with a repeating blind-tooled roll, with large ornaments in blind at the angles. The spine is richly tooled in gold with decorative ornaments. The title, "MUSEUM REGIUM", surmounted by a crown with the monogram of King Frederick IV of Denmark, is stamped in gold in the 2nd compartment. The text and plates are in excellent condition with a few trivial blemishes, early signature washed out, light toning to a few plates, and light yellowing at the fold of one plate. There are some extensive pencil annotations in the numismatic section. The central gatherings are sprung. Illustrated with an engraved frontispiece and 54 engraved copper plates of specimens, artifacts, and coins. 2 of the plates are double-page. 2 plates in the final sequence are numbered XXI and "Tabulae"(i.e. image) XXIII/XXIV in the same sequence are engraved on one plate. [The first edition had only 37 plates. The 1699 supplement included an additional 3 plates.] The Royal Danish Kunstkammer, an impressive collection of naturalia and artificialia (described below), was founded by King Frederick III (reigned 1648-1670) in 1650, shortly after his ascension to the Danish throne, and was continued by his son, Christian V (reigned 1670-1699), to whom the first edition of the catalogue (1696) was dedicated. The nucleus of the museum was the famed Wunderkammer of the eminent Danish naturalist, historian, and runologist Ole Worm, whose collection of natural history specimens and ethnographic artifacts was purchase by King Frederick upon Worm's death in 1654. The Kunstkammer existed until 1825 when its collections were dispersed among the many specialized museums created around that time. This catalogue is an invaluable illustrated record of the collections as they stood in the early 18th century. The author, the comparative anatomist Holger Jacobson (latinized as Oliger Jacobaeus), was a student of Nicolas Steno and the son-in-law of the physician and anatomist Thomas Bartholin. He taught philosophy, history, geography, and medicine at Copenhagen University, and served as keeper and librarian of the royal collections. In 1687, Frederick's son Christian the Fifth (reg. 1670-99) ordered Jacobson to write a complete catalog of the collection. Jacobson's first edition of the museum collection was printed in 1696. A supplement followed in 1699. The collections continued to grow in size and prominence, and an updated version of Jacobson's catalogue was soon required. This new edition of 1710 was further expanded and edited by Johannes Laverentzen(c.1648-1729), director of the royal printing house, who dedicated it to King Frederick IV of Denmark (reigned 1699-1730). The museum catalogue is divided into two parts. The first part contains seven sections, describing and depicting such diverse items as mummies, narwhal horns, conjoined twins, cutaneous horns, and numerous New World specimens, including an armadillo, anteater, bird of paradise, and pineapple; The second part consists of five sections, describing precious objects made from gold (such as the golden horn from Ole Worm's collection), silver, bone, stone etc., weapons and instruments of cultures worldwide, relics from antiquity, mechanical and optical instruments (such as a machine for calculating astronomical phenomena), and the extensive numismatic collection. (For further detail, see below.) 37 of the plates are the work of J. Erichsonig after Benedict Grothschilling and depict an array of artifacts and specimens. In addition to the large plates, each of the chapters is illustrated with a decorative headpiece, tailpiece, and large engraved initial illustrated according to the category of artifact included in that chapter. For example, for Section I, "On Humans & Quadrupeds", the initial depicts a sarcophagus opened to reveal its occupant; the headpiece shows an array of animals and animal skeletons with pride-of-place given to a human skeleton flanked by elephant tusks and dissected fetal corpses. The whole scene is festooned with garlands of claws, hooves, and human hands. The museum catalogue is divided into two parts. The 'Pars Prima' contains seven sections relating to 'Naturalia' dealing in turn with 1. humans and quadrupeds, 2. birds, 3. fish, 4. shells, 5. reptiles, and 6. insects; followed by 7. metals, minerals, and earths. 'Pars Secunda' focuses upon 'Artificialia' and has five sections corresponding to: 1. artificial objects of metal, wood, bone, horn and amber; 2. weapons, clothes, implements and utensils from India, Turkey, Greenland and elsewhere; 3. antiquities; 4. scientific and mechanical apparatus; and 5. coins, medals, seals. The striking plates show a curious mixture of man-made and natural objects, including two Egyptian mummies, a petrified foetus, and a collection of remarkable horns (including the famous horned hares), numerous coins, medals, birds, fish, shells, serpents, insects, as well as fossils and minerals. The ethnographic cabinets containing costumes and implements, were strong in Scandinavian material and antiquities, including a kayak and clothing from Greenland (the Greenlanders are depicted on one of the plates), the Danish horn made of gold and adorned with runes from Worm's collection, the 'runeless horn' and the famous 12th-century 'Gunhild Cross' made of walrus ivory, bought by Christian V in Copenhagen in 1684 (an early instance of accession by auction purchase.). FIRST EDITION THUS, GREATLY-EXPANDED FROM THE FIRST EDITION (1696.).Pub. Ovidii Nasonis MetamorphoseÅn libri quindecim, donati argumentis compendiarijs, & adnotationibus marginalibus D. Gyberti Longolij illustrati. Accesserunt & ad finem libri Henrici Glareani adnotationes non uulgares

Bound in contemporary alum-tawed pigskin, tooled in blind, with one intact and one fragmentary clasp. The binding is lightly worn, with small defects at one corner, the head of the spine and the front hinge, but the majority of the tooling is very clear. The decorative rolls depict Christ, King David, St. Paul, a winged cherub's head, and vegetal motifs. The central compartment has repeating sheaves of wheat. A tall copy, the contents lightly toned. There is a light damp-stain to the title page and in the lower margin of gathering F, a small wormhole from page 430 to the end, a tiny hole in the blank margin of the title, and a small stain in the lower margin of lvs. Ii8 and Kk1. Gymnicus' hippocampus device is on the title; the text features small woodcut initials showing dolphins, a stag, a man playing the pipes and dancing with a woman while a dog watches, an urn with flowers, a unicorn. There are three early ownership inscriptions on the front free endpaper, one of them of a certain Stephan Schrade of "Corona" (?BraÈov, Romania). Ovid's poem is accompanied by the commentaries of the Dutch humanist physician Gilbert de Longueil (approx. 1507-1543), Professor of Greek at Cologne University; and the Swiss humanist, poet and music theorist Heinrich Glarean (1488-1563), contemporary and friend of Erasmus. Each of the fifteen books is preceded by an 'argumentum' (a learned summary of the book). They are here attributed to "Donatus" but are more commonly known as the "Lactantian" argumenta. Extremely rare. Illinois only in North America. "With the 'Aeneid' Vergil had realized the grandiose project of a Homeric-style poem, a national epic for Roman culture. Ovid in realizing his ambitions for a work of great scope takes another direction. The outer form was to be epic (the hexameter is its distinctive mark), as was the ample scale, but the model, which is based on Hesiod, is that of a "collective poem", one that gathers a series of independent stories linked by a single theme. Ovid's ambition is grand: to realize a universal work, one that goes beyond the limits of the various poetic creeds. The very chronology of the poem confirms this. It is boundless, going from the beginning of the world down to Ovid's day, and thus realizes a project long-desired and hitherto only sketched out in Latin culture. "The fundamental characteristic of the world described by the 'Metamorphoses' is its ambiguous and deceptive nature, the uncertainty of the boundaries between reality and appearance, between the concreteness of things and the inconstancy of their appearances. The characters of the poem behave as if lost in this insidious universe, which is governed by change and error; disguises, shadows, reflections, echoes, and fugitive semblances are the snares in the midst of which the humans move about, victims of the play of fate or the whim of the gods. Their uncertain action and the natural human disposition to err are the object of the poet's regard, now touched, now amused; they are the spectacle that the poem represents." (Gian Biagio Conte's "Latin Literature, A History").Dialogo de la Seraphica Vergine Santa Catharina da Siena: el qual profondissimamente tratta de la divina providentia: de quasi tutti li peccati mortali & de molte altre stupende, & maravigliose cose: como in el suo repertorio lucidamente appar. Insieme con la sua vita, & canonizatione & alcuni notabili capitoli composti in sua gloria, & laude. Nuovamente revisto, & con summa diligentia castigato

A very fine, fresh copy in early vellum (corners bumped, light soiling, lacking ties) with the original blue and white silk end-bands intact. Bright and clean internally. With the Sessa cat and mouse device on the title and final leaf. Early, faded inscription and early stamp of the Carthusian library at the Reichskartause Buxheim (Buxheim Charterhouse) on the t.p. The library was dispersed after secularization in 1803. A rare edition of "Il libro della divina dottrina", "The Book of Divine Doctrine" (also called the "Dialogue"), the culminating theological work of the Dominican tertiary mystic Saint Catherine of Siena (canonized 1461, feast day 29 April). Catherine composed the book, which takes the form of an inner conversation between the soul and God, two years before her death. The book was first published in Bologna ca. 1475 and reprinted five times in the fifteenth-century. In 1504 Lazaro di Soardi printed an edition at Venice. The next was printed by Cesare Arrivabene in 1517; the third by Sessa in 1540. This 1548 ed. is the fourth 16th c. edition. This edition includes a life of the saint, composed by an unnamed Dominican, drawn from the documents presented during the canonization process. The dedication to Isabelle d'Este, wife of GiovanniGaleazoSforza, duke of Milan, andBeatrice d'Aragona,wife ofLodovico Sforza, duke of Barri, is taken from the 1494 edition, in which this vita first appeared. The Italian translation of the text (from the Latin original) is attributed to Baldassare Azzoguidi, publisher of the first edition. Tradition held that Catherine dictated the work to her secretaries over the course of five days while she was in the throes of ecstasy. Historical evidence indicates that it was probably dictated over a period of months between December 1377 and October 1378. "The 'Dialogue' deals with the whole plan of salvation, with particular emphasis on Jesus Christ as the Bridge which unites man to God. Although it contains a rich theological doctrine, it does not present a systematic development of ideas. Catherine is not interested in speculative scholasticism; rather, she is moved by practical considerations. This is obvious from the first chapter of the Dialogue , where she addresses four petitions to the Eternal Father: (1) for herself; (2) for the reformation of the Church; (3) for the needs of the whole world; and (4) a petition to divine providence to provide for things in general and in particular. The rest of the Dialogue is taken up with the Father's response to these four petitions with interjections now and again from Catherine. "God's love for us in creation is so great that, according to Catherine, it reaches a point of 'madness'. In the last chapter, overcome by the realization of this 'madness' of love, she writes: 'I confess and do not deny that you loved me before I existed and that you loved me unspeakably, as if you were mad with love for your creature.' "Contemplating the Incarnation, Catherine cannot understand how God can love us so much that he would take on the lowliness of human nature: 'O abyss of love, what heart can help breaking when it sees such dignity as yours descend to such lowliness as our humanity? . For what reason? Love. By this love, O God, you have become man, and man has become God.' As in the case of Creation, so again, in the context of the Incarnation, Catherine exclaims that God must be 'mad' with love for us: 'It seems, O abyss of love, as if you were mad with love for your creature, as if you could not live without him; and, yet, you are God who has no need of us.' "The death of Jesus Christ is the supreme expression of God's mad love for man. Addressing Jesus Christ directly -something which she does rarely- Catherine asks: 'O loving madman, was it not enough for you to become incarnate, without also wishing to die?' She is convinced that nails would never have held Jesus Christ to the cross, if love had not held him there."(O'Driscoll) "Catherine was the youngest of 25 children born to a lower middle-class family; most of her siblings did not survive childhood. At a young age she is said to haveconsecrated her virginity toChristand experienced mystical visions. Convinced of her devotion, Catherine's parents gave her a small room in the basement of their home that acted as a hermitage. She slept on a board, used a wooden log for a pillow, and meditated on her only spiritual token, a crucifix. She claimed to have received an invisible (for humility) stigmata by which she felt the wounds of Christ. "At the age of 19, after a three-year seclusion, Catherine experienced what she later described as 'spiritual marriage' to Christ. In this vision, Jesus placed a ring on her finger, and her soul attained mystical union with God. She called this state an 'inner cell in her soul' that sustained her all her life as she traveled and ministered. "Catherine became a tertiary (member of a monastic third order who takes simple vows and may remain outside a convent or monastery) of theDominican order(1363), joining the Sisters of Penitence ofSt. Dominicin Siena. She rapidly gained a wide reputation for her holiness and her severeasceticism. In her early twenties she experienced a 'spiritual espousal' to Christ and was moved to immediately begin serving the poor and sick, gainingdisciplesin the process. "Her ministry eventually moved beyond her localcommunity, and Catherine began to travel and promote church reform. When the rebellious city ofFlorencewas placed under an interdict by PopeGregory XI(1376), Catherine determined to take public action for peace within the church and Italy and to encourage a Crusade against theMuslims. She went as an unofficial mediator toAvignon with her confessor and biographer Raymond of Capua. Her mission failed, and she was virtually ignored by thepope, but while at Avignon she promoted her plans for a Crusade. "It became clear to her that the return of Pope Gregory XI to Rome fromAvignon-an idea that sheOpera. Phi. Melanchthonis & aliorum . scholijs, annotationibus & novis argumentis illustrata . partim nunc primum publicatis. Adiectis etiam figuris egregiem depictis

Virgil. Virgilius Maro, Publius (70-19 B.C.) Illustrated with 18 full-page woodcuts attributed to Jos Murer (1530-1580). Bound in contemporary blind-stamped pigskin over wooden boards, 1 of 2 clasps preserved, binding worn and soiled, with small losses to the pigskin at the extremities. Internally a very fresh copy; ink blot in text on leaf f1; upper outer corners of central gatherings with minor dog-earing; a few contemporary notes in Bk. III of the Aeneid. 16th c. ownership entry on front paste-down. With the contemporary inscription: "ex libris Guberti à Salicibus nec non amicorum"("Guibert (or Gilberto?) of Asturias? and friends"). This edition of Vergil's works, with notes by Philip Melanchthon (1497-1560), features an introduction by Josse Bade of Asse (aka Jodocus Badius Ascensius) (1462-1535), more than 100 pages of notes on the Bucolics and the Georgics by Johannes Fries (1505-1565) and Christoph Hegendorf (d. 1541); as well as "arguments" for each book of the Aeneid. In addition to the Eclogues, Georgics, and Aeneid, this edition contains the minor poems of the "Index Vergiliana", various epigrams, and Maffeo Vegio's (1406-1458) conclusion of Vergil's epic, the "Aeneidos Supplementum", the so-called "13th book" of the Aeneid. THIRD EDITION with these woodcuts. The first edition with these illustrations was printed in 1561 at Zürich, also by Froschauer. A second edition was printed in 1563 at Frankfurt by Sigmund Feyerabend. This 1564 Froschauer edition was already underway in 1563 (the date of the colophon.).- $8,500

- $8,500

Le Soleil Au Signe du Lyon d’ou quelques paralleles sont tirez, avec les tres-Chrestien, tres-Iuste, & tres-Victorieux Monarque Louys XIII. Roy de France & de Navarre, en son Entrée triomphante dans sa Ville de Lyon. Ensemble Un sommaire recit de tout ce qui s’est passé de remarquable en ladite Entrée de sa Majesté, & de la plus Illustre Princesse de la terre, Anne d’Austriche, Royne de France & de Navarre, dans ladite Ville de Lyon le 11. Decembre 1622

SPLENDID CEREMONIES. GRAND ENTRIES bound with Reception de tres-chrestien, tres-iuste, et tres-victorieux monarque Louys XIII. Roy de France & de Navarre, premier Comte & Chanoine de l'Eglise de Lyon: et De Tres-chrestienne, Tres-auguste, & Tres-vertueuse Royne Anne d'Austriche: Par Messieurs les Doyen, Chanoines, & Comtes de Lyon, en leur Cloistre & Eglise, le XI. Decembre, M. D. XXII. Lyon: Par Jaques Roussin, 1623 FIRST EDITION OF BOTH WORKS Folio in 4s: 29 x 20 cm. Soleil: Ï1(=A1?) *4 Î'4(-Î'1) B-R4 (R3 blank) S-X4 Y6 [$3 signed; -*2, *3, D1, G1, H2, K1, L1, M3, P1]. 94 leaves, pp. [10] (title printed in red-and black, blank, 4pp. dedication, 3pp. to the reader, imprimatur) 3-180. [=x, 178] With 12 engraved plates (11 integral with the text), of which 1 is folding (not integral). "Reception": A-G4 H6 [$3 signed; -A1, E2, E3]. 34 leaves, pp. 1-2 (title, blank) 3-67, blank. With 7 engraved plates (3 integral with the text), of which 4 are folding (not integral). Collated complete against the BnF copies. Bound in contemporary parchment (mild soiling and wear, a little rumpled.) On the spine, title in ink manuscript ("L'entrée/ De Louys/ XIII a/ Lione"). Text in fine condition with some very mild toning, occasional spotting, and a few minor stains. A few lvs. (C1/4 second work) lightly browned. A few clean tears repaired, no loss. Small marginal tears to a few lvs., far from the text. Bookplate of Paul and Marianne Gourary to the front paste-down. Ownership signature of "d. Rubto Galilei" to the front paste-down. Two works describing and illustrating the entry of Louis XIII (1601-1643, r. 1610) and his Queen consort Anne of Austria (1601-1666, m. 1615) into Lyon on 11 December 1622. Richly illustrated with engravings by Charles Audran, G. Autgers, Pierre Faber, Grégoire Huret, Philippe de Malley and David van Velchem. This royal tour marked the end of the first Huguenot rebellion, which was resolved by the Treaty of Montpellier, signed 18 October 1622. With scarcely six weeks to prepare, Lyon welcomed the triumphant king and queen - the titles' emphasis (very Christian, very just, very victorious) is telling - and celebrated their reign with pomp and spectacle. Louis XIII is here compared to the sun, a title more usually applied to his son Louis XIV, le roi soleil. The royal entry at Lyon was one of a number of celebratory stops made by the royal couple on the way from Montpellier (where the king had just signed the treaty.) Other regal celebrations were held in Arles (October 30, 1622), Aix (November 3 and 10, 1622), Marseille (November 7, 1622) and Avignon (November 16, 1622). These two related two works describe the entry, the monuments, ceremonies, and festivities. The "Sun in the sign of Lyon" describes the different monuments, composed of triumphal arches, columns, fountains, etc. erected for the occasion. It is illustrated with a vignette on the title with the arms of Lyon, drawn and engraved by Pierre Faber, and with 12 figures, including 11 full page and one folded out of text, by Faber, D. de Mallery, Grégoire Huret, Van Velkhem and G. Autguere; they represent the different monuments described in the work. One of the engravings shows the magnificent fireworks display over the river Saône. The present volume belonged to Ruberto Galilei (Roberto, born 1595), a Lyon-based cousin (fifth, once removed; nevertheless Favaro describes him as "sinceramente affezionato a Galileo") of the renowned scientist Galileo Galilei (1564-1642). Ruberto acted as an intermediary for Galileo's foreign correspondence - with Diodati, Peiresc, Mersenne et al. - after his inquisitorial trial in 1633. The cousins also corresponded, especially concerning the movement and publication of books. Ruberto moved from Florence to Lyon as a young man, and so possibly witnessed this joyeuse entrée. [1] An earlier issue of the Reception with a 1622 date (surely a nicety rather than a sign that the work was conceived and published in 20 days) is recorded, but is otherwise identical. [2] Fa- $15,000

- $15,000

Euphues The Anatomie of Wit: Very pleasant for all Gentlemen to read, and most necessary to remember. Wherein are contained the delights that wit followeth in his youth, by the pleasantnesse of loue: and the happinesse he reapeth in age, by the perfectnesse of wisdom. By Iohn Lylie, Master of Art. Corrected and Augmented. [And] Euphues and his England. Containing his Voyage and Adventures: Mixed with sundry pretty Discourses of honest Loue, the Description of the Country, the Court and the manners of the Ile. Delightfull to be read, and nothing hurtfull to be regarded: wherein there is small offence by lightnes giuen to the wise, and lesse occasion of loosenesse proffered to the wanton. By Iohn Lilie, Master of Arts. Commend it, or amend it

Lyly, John (1554?-1606) An unsophisticated copy in contemporary blind-ruled sheep (wear to the extremities, small defects at head and tail of spine, upper board with two fractures in the leather, corners bumped. Internally generally fresh. There is marginal staining and a little wear to the edges of the title page and final leaf; the upper margins of the closing gatherings have minor abrasions. Some contemporary under-scoring and other minor blemishes. Provenance: numerous early owners' names on the front flyleaf, including the inscription "Mary Cooper, her booke". John Lyly's celebrated "Euphues", "arguably the first English novel" was published as two separate, closely-associated works, the first "Euphues. The Anatomy of Wit", in 1578; the second "Euphues and his England", in 1580. Enormously popular, the book went through many editions into the 17th c. "John Lyly (1554-1606) was a native of Kent, and, in his day, a noted son of Oxford. His career was one of strenuous effort, ill requited because ill-directed. His nice, fastidious temperament, which marked him off from the roaring section of university wits, seems to have rendered him ineffective in actual life. At Oxford, he missed recognition; his ambition to succeed to the Mastership of the Revels was quietly ignored; while his closing years, passed in penury and neglect, form a saddening sequel to the efforts of one, who, in his time, had adorned the stage, had beautified the conversation of exquisites 'of learned tendency' and had been the fruitful occasion of much wit in others. "The work for which he is famous appeared in two installments. 'Euphues, the Anatomy of Wit' was 'lying bound on the stationers stall' by the Christmas of 1578; 'Euphues and his England', the second part, appeared in 1580. Together, they form an extensive moral treatise, and, incidentally, our first English novel. The whole hangs together by the thinnest of plots, which is, indeed, more a means to an end than an end in itself. Euphues, a young man of Athens, arrives at Naples, where he forms a friendship with young Philautus. He falls in love with Lucilla, the betrothed of Philautus, and is duly jilted by that fickle mistress. "This is all the action of 'The Anatomy of Wit': but the moralizing element is something more considerable. The ancient Eubulus discourses on the follies of youth; Euphues, himself, on the subject of friendship. The complications brought about by the action of Lucilla lead to much bitter moralizing upon fickleness in general, while Euphues, jilted, discusses his soul and indicts 'a Cooling Carde for all Fond Lovers.' Over and above all this, the work contains the hero's private papers, his essays and letters; and opportunities are seized for inveighing against dress, and for discoursing upon such diverse subjects as marriage and travel, education and atheism. In 'Euphues and his England', the scene changes from Italy to England. The two friends, now reconciled, proceed to Canterbury, where they are entertained by one Fidus, a pastoral figure of considerable attractiveness; Philautus soon becomes involved in the toils of love, while Euphues plays the part of a philosophical spectator. The former lays siege to the heart of one whose affections are already bestowed, and so, with philosophy for his comfort, he enters upon the wooing of another, with more auspicious result. This brings the action to a close, and Euphues leaves England, eulogizing the country and the women it contains, and returns forthwith to nurse his melancholy within his cell at Silexedra. "The style, known as Euphuistic, won a following in its day, and has since become one of the most familiar of literary phenomena. Lyly aimed at precision and emphasis, in the first place, by carefully balancing his words and phrases, by using rhetorical questions and by repeating the same idea in different and striking forms. Alliteration, puns and further word play were other devices employed to the same end. For ornament, in the second place, he looked mainly to allusions and similes of various kinds. He alludes to historical personages found in Plutarch and Pliny, to mythological figures taken from Ovid and Vergil. But his most daring ornamentation lies in his wholesale introduction of recondite knowledge; he draws similes from folklore, medicine and magic, above all from the 'Natural History' of Pliny, and this mixture of quaint device and naïve science resulted in a style which appealed irresistibly to his contemporaries. "Apart from its prose style, the 'Euphues' of Lyly exercised considerable influence upon its author's contemporaries. On Shakespeare, to mention only one, its effect is marked. Some of the dramatist's characters, such as his pairs of friends, the sententious old man Polonius and the melancholy philosopher Jacques, recall 'Euphues' in different ways. Verbal resemblances also exist: Shakespeare's utterances on friendship, and his famous bee-passage, place his indebtedness beyond all doubt, even supposing his numerous similes drawn from actual or supposed natural history to be but drafts made upon the common possessions of the age." (The Cambridge History of English and American Literature in 18 Volumes, Volume III. Renaissance and Reformation, XVI. Elizabethan Prose Fiction. § 3. John Lyly.). 17th EDITION of "Anatomie of Wit"; 19th EDITION of "His England". THE LAST of the 17th c. EDITIONS.Loci Praecipui Theologici. Nunc denuo cura et diligentia summa recogniti, multisque in locis copiose illustrate, Cum appendice disputationis de Coniugio. His additae sunt recens definitiones multarum appellationum, quarum in Ecclesia usus est, traditae ab eodem autore Torgae & Witebergae: Anno 1552. & 1553. Ad calcem huius operis accessit, locorum scripturae in hoc explicatorum, itemque capitum totius libri, nec non rerum atque verborum memorabilium trigeminus Index quam diligentissime conscriptus

Melanchthon, Philip (1497-1560) Bound in contemporary blind-stamped pigskin over wooden boards (one clasp preserved, light wear and soiling). The text is in excellent condition, with just 2 lvs. (d7-8) lightly spotted, and a small natural paper flaw to the blank upper margin of leaf p6 (just touching the page number). There are a few contemporary annotations in gathering f. Provenance: André Hachette (cat. 1953, no. 85).- Charles von der Elst.- Pierre Berès (catalogue Livres rares. Six siècles de reliures, 2004, no. 46). A superb contemporary blind-stamped pigskin binding, dated 1564 and signed M.O.C., by Thomas Krüger of Wittenberg, with full-length portrait panel stamps of Martin Luther (157 x 89 mm.) and Philip Melanchthon (156 x 90 mm.) based on portraits by Lucas Cranach the Younger (1515-1586). A binding bearing only the portrait of Melanchthon on the upper board is reproduced by Mirjam Foot in her article: "A Binding by Thomas Krüger 1573" (The Book Collector, 1981). The Melanchthon panel stamp: Based on Cranach's 1561 woodcut of Melanchthon (Hollstein VI.151.48c iii/vi; Bartsch XI.442.153; Dodgson II.347.31), the panel stamp (EBDB p002950; Haebler I 250, VIII) by Thomas Krüger bears the date 1563 and Krüger's initials. A simplified form of Cranach's device can be seen at the foot of the plate, beneath the scroll with Melanchthon's name. The Cranach emblem, depicting a serpent with upright bat wings holding a ring in its mouth, was granted by Duke Friedrich the Wise to Cranach's father in 1508. While the background in Cranach's woodcut is blank, Krüger has added an elaborate architectural frame with a landscape in the far background, in which the Wittenberg Pfarrkirch can be discerned. The church view was almost certainly inspired by the background on the stamp with the portrait of Luther (see below). Two putti bear shields. One has the arms of Saxony; the other shows Melanchthon's crest, featuring a serpent entwined on a cross, representing the bronze serpent made by Moses to cure the Israelites of poisonous snakebites during their forty years in the wilderness. The engraver has modified Cranach's portrait by replacing the closed book in Melanchthon's hand with an open one, in which is written one of Melanchthon's epigrams ("Nullius est felix conatus etutilis unquam, Consilium si non detque iuvetque Deus"). The Luther panel stamp: The undated panel stamp (EBDB p002949; Haebler I 250, VII), signed with Krüger's initials, is based on a ca. 1546 woodcut by Cranach. The Luther and Melanchthon stamps were clearly conceived of as a pair. As with the Melanchthon stamp, Cranach's serpent device can be seen at the foot of the plate, beneath the scroll with Luther's name; once again, Krüger has set Luther within an elaborate architectural frame in which putti bear shields, this time with the arms of Wittenberg and Luther's crest (the "Luther rose"). The landscape in the far background, with a view of Wittenberg, corresponds to the one in Cranach's woodcut. The engraver has modified the book held by Luther, opening it to reveal the text of 2 Corinthians 12:9 ("virtus mea in infirmitate perficitur") and Isa 30:15 ("In silentio et spe erit fortitudo vestra"). The text: "You cannot find anywhere a book which treats the whole of theology so adequately as the 'Loci Communes' do. Next to Holy Scripture, there is no better book." -Martin Luther Philip Melanchthon's epochal "Loci Communes Rerum Theologicarum Seu Hypotyposes Theologicae" ("Fundamental Topics of Theology, or a Theological Framework") was the first Protestant work of systematic theology. While teaching at Wittenberg, Melanchthon "came under the influence of Martin Luther and began to study theology. The proclamation of God's grace freely given became the enduring mainstay of his life. As this experience penetrated his intellectual world, it led him to develop the reformation's message systematically. Melanchthon's most important work, the 'Loci Communes Theologici', through which he created not only the first dogmatic of the Lutheran reformation but also a new genre in theological literature, arose out of the application of scriptural authority to his work on the Bible itself. "At Wittenberg, part of the curriculum for theologians still included lecturing on the Sentences of Peter Lombard. Melanchthon wanted to circumvent this normative structure for dogmatics and to offer instead a scripturally based exposition of doctrine. For this purpose he employed an ancient method, recommended by Desiderius Erasmus, of noting the basic concepts- 'topoi', or 'loci communes'- of a text in order to appropriate more fully its content. Whereas Erasmus continued to impose upon the text his own list of 'loci communes', Melanchthon required that the 'loci' and their organization arise out of the text itself."(Encyclopedia of the Reformation) What is remarkable -and new- about the system employed by Melanchthon in the "Loci" is that it is the first system of doctrinal positions drawn solely from the Word of God. In his preface to the first edition, Melanchthon gives a list of the topics -"the principal heads of theological science"- which he considered fundamental to the doctrines of faith and piety, and upon which his entire scheme hung: God, Unity, Trinity, Creation, Man, the strength of Man, Sin, the fruit of Sin, Vice, Punishment, Law, Promises, Renewal Through Christ, Grace, The fruit of Grace, Faith, Hope, Charity, Predestination, Sacramental signs, the estates of Man, Civil Offices, Bishops, Condemnation, and Blessedness. "The book marks an epoch in the history of theology. It is an exposition of the leading doctrines of sin and grace, repentance and salvation. It is clean, fresh, thoroughly Biblical, and practical. Its main object is to show that man cannot be saved by works of the law or by his own merits but only by the free grace of God in Christ as revealed in the Gospel. It presents the living soul of divinity in contrast to the dry bones of degenerate scholasticism."(Sch- $20,000

- $20,000

Ragguaglio delle Antichità e Rarità che si conservano nella Galleria Mediceo-Imperiale di Firenze. Parte I [all published] Opera Di Giuseppe Bianchi Custode Della Medesima.

MUSEUMS. Bianchi, Giuseppe (b. ca. 1727) An exceptional copy bound in contemporary carta rustica. A few leaves creased, boards very lightly soiled. The text is adorned with attractive woodcut initials and headpieces. Printed on thick, crisp paper with broad margins; a number leave with the lower edges untrimmed. A crisp, bright copy in original three-quarter calf and speckled paper over boards, spine with floral ornaments. The text is adorned with attractive woodcut initials and headpieces. First edition of the first guide to one of the world's most important museums. This guide to the Medici collections of the Uffizi Gallery was written by the museum's first custodian, who had been appointed after the gallery's conversion to a public institution under the terms established by the last of the Medici, the Palatine Electrix Anna Maria Ludovica, in 1737. The custodian, Giuseppe Bianchi, is a notorious figure. He was later found to have robbed the Uffizi of works of precious metal, which he melted down and sold. He was condemned to exile for his perfidy. (See Barrochi and Bertelà, "Danni e furti di Giuseppe Bianchi in Galleria, Labyrinthos 13/16 (1988-89), 321-336.) Bianchi's guide, published in the same year that the British Museum opened to the public, is an important record of the disposition and scope of the newly "public" collections in the period prior to their dramatic reorganization by Grand Duke Pietro Leopoldo of Lorraine (1780-82). In some instances, the notices in the guide are the earliest extant record for some works in the collections. The portable and scholarly guide is similar in format and composition to Pasquale Massi's 1792 guide to the Vatican Museums, which Bianchi's guide predates by a generation. Bianchi prefaces his tour with a history of the construction of the Uffizi palace, designed and begun by Vasari in 1560 and completed -following Vasari's design- by Alfonso Parigi and Bernardo Buontalenti in 1581. This is followed by a description of the various elements that make up the entire palace complex. The formal guide to the galleries begins with a detailed description of the decorative program of the frescoed ceilings and the series of portraits that line the walls beneath them. This is followed by descriptions and commentaries on each of the 62 statues and 92 busts housed in the galleries in this period. Francesco I was the first Medici to add ancient marbles to the newly completed Uffizi, and these ancient sculptures were juxtaposed with contemporary Renaissance masterpieces. Thus we find in Bianchi's guide the famous Medici Venus, the Niobe group, Bandonelli's Laocöon, and Michelangelo's Bacchus. The sarcophagus of Hippolytus is absent, since it was still in the Palazzo Medici Riccardi in 1759. Next, Bianchi takes us into the Camera dei Pittori. Yet, here he is unable to give a comprehensive discussion. This is due, in large part, to the sheer size of the collection but also to the fact that the painting collection has changed so much over the years, some of the paintings having been transferred to the Pitti Palace, others that formerly hung in the Palace having come to the Gallery, and others still having been given as gifts to great lords, or used to decorate villas. Moreover, the paintings are in many media: oil, tempera, fresco, and encaustic. Bianchi decides to focus on the collection of artist self-portraits, which are divided into the three principal schools (arrived at by the consensus of the most famous scholars of the art of painting): Romana, Lombarda, and Oltramontana. Here we find the famous self-portrait of Raphael. From here we pause briefly in the Camera delle Porcellane before entering the Camera degl' Idoli with its collection of 300 Greek, Roman, Etruscan and Egyptian bronzes, which Bianchi considers in detail. Next we enter the Camera delle Arti, where we find paintings by Raphael, Andrea del Sarto, Leonardo, Botticelli, Mantegna, and Fra Angelico. In the Camera de' Fiamminghi are housed 140 paintings by northern European- $6,800

- $6,800

Architectura Recreationis. [and] Architectura Civilis. [and] Architectura Privata

ARCHITECTURE. Furttenbach, Joseph (1591 - 1667) A sammelband of three of Furttenbach's major architectural treatises. With 3 engraved frontispieces, printed titles in red and black, and a total of 89 folding plates of various sizes (the largest of them 370 x 300 mm.) showing residences, civic structures, palaces, churches, elaborate gardens and grottoes, pavilions, and theaters. All works with elaborate decorative woodcut head- and tail-pieces and decorative initials, German text in Gothic type throughout. The plates by various engravers, largely after Furttenbach himself. Exceptional copies, complete with all plates, the text and plates on the whole bright and crisp. Bound in contemporary full vellum (lightly soiled, minor wear to extremities) with a decorative title label (gilt-tooled with citron wash.) All plates are folding, having been tipped in on guards at the time of binding so that they might fold out easily, avoiding tears. A few plate edges are a bit curled and dust soiled where they extend outside of the text block; there is scattered light foxing in the upper margins and a few small stains; a few plates have discoloration along the fold. The only other blemishes are on the two final plates of the third work, each of which is lightly browned along one fold and has one small hole, within the plate but not affecting the image. Provenance: 1. With the engraved armorial bookplate, "Bibliotheca Velseriana", possibly that of Carolus Velser (1635-1697). 2. Later stamp (Lugt 1114) of "G. W. Günther, Nuremberg" at foot of titles and on binding and with his signature on rear paste-down (Lugt 1115). 3. Bookplate of Emily, Marchioness of Landsdowne (1819-1895). The practicing architect Joseph Furttenbach (1591-1667), "author of the lone series of architectural textbooks to appear in Germany during the Thirty Years' War", was heavily influenced by Italian architecture, which he studied during his 10-year sojourn in that country. Upon his return to his native Ulm, he adapted Italian principles to his designs for German buildings, including his own townhouse (which he described in his "Architectura Privata"), with its famous garden and private museum-library. "Furttenbach is a fascinating figure. He left Germany at the age of sixteen for a ten-year stay in Italy, where he studied- among other things-stage design under Giulio Parigi in Florence. While in Italy he decided to become an architect and merchant, and he brought both interests back to his native Ulm in 1621. Ten years later he became a municipal architect; in 1636 he became a senator. In addition to practicing architecture he was also active as a garden designer, pyrotechnician, and military engineer. All of these pursuits found an outlet in his numerous books, which began in 1626 with a description of his Italian travels and appeared regularly until the 166os."(Millard) I. Architectura Civilis (1628): "Furttenbach's 'Architectura civilis' (1628) is his most significant contribution to architectural theory. The preface starts with a lengthy history of this 'noble art of architecture,' which, after a review of classical traditions, focuses upon 'Italians of noble Roman descent.' His architectural preferences are also clearly apparent, as 'it is well known that in Italy the most exquisite, the most artistically rich and satisfying, and the strongest buildings are to be found than in any other place in the whole of Europe.' From this thesis, Furttenbach goes on to consider architecture under three rubrics: palaces, pleasure pavilions, and gardens; churches and chapels; and hospitals. His goal is to bring the principles of symmetry and correct proportion to the North. Like many of his sixteenth-century predecessors, Furttenbach saw his task as one of continuing the line of the humanist Renaissance tradition."(Millard) II. Architectura Recreationis (1640): Rebuilding after War In this remarkable book on civil architecture and advanced theater design, Furttenbach presents house and garden designs for various tiers of societ- $24,000

- $24,000

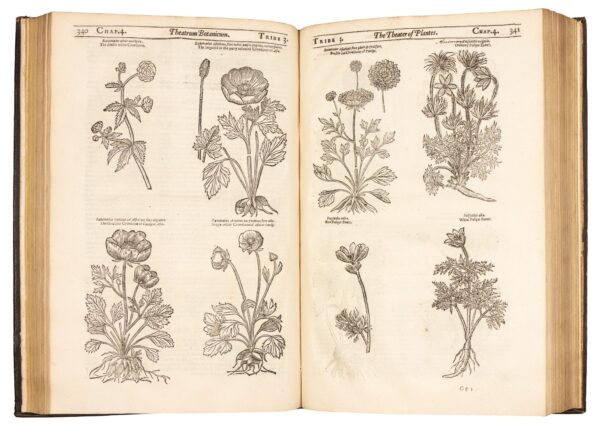

Theatrum Botanicum: The theater of plants.: Or, An herball of a large extent: containing therein a more ample and exact history and declaration of the physicall herbs and plants that are in other authours, encreased by the accesse of many hundreds of new, rare, and strange plants from all the parts of the world, with sundry gummes, and other physicall materials, than hath beene hitherto published by any before; and a most large demonstration of their natures and vertues. Shevving vvithall the many errors, differences, and oversights of sundry authors that have formerly written of them; and a certaine confidence, or most probable conjecture of the true and genuine herbes and plants. Distributed into sundry classes or tribes, for the more eas